Opinion

Miami After Dark: Kenny Schachter on Disaster, Death Threats, and Killer Deals at Art Basel Miami Beach

Our columnist donned his shades and hit the Southern sin city once again in pursuit of the ultimate rush: art-market gossip.

Our columnist donned his shades and hit the Southern sin city once again in pursuit of the ultimate rush: art-market gossip.

Kenny Schachter

Before heading off to Miami Beach for the sixteenth edition of the Art Basel there, I bumped into a prominent art-world public-relations exec who exaggeratedly fist-pumped in exaltation at not having to go to the fair this year (as his notable London client had notably bowed out). I understand the disinclination—the endless fashion parties and non-art events far outnumber everything else.

I even appreciated Adam Lindemann’s very public avowal in 2011 to boycott the fair: “I’m through with it, basta. It’s become a bit embarrassing, in fact, because why should I be seen rubbing elbows with all those phonies and scenesters, people who don’t even pretend they are remotely interested in art?” Adam was entirely correct; but like him, I visited the fair that year and every other since its inception. It’s the tenacious tug of FoMa (the fear of missing art) that invariably hooks us, so here we go again, again.

The dolphin says it all. Photo-collage by Kenny Schachter.

Why does everyone love to hate on Miami Basel? It’s the only fair from which I get sent PR images of C-list celebs attending D-list parties (in real-time). And besides the social-mongering interlopers, the art is not quite up to snuff in comparison with the Swiss iteration. Then there is Miami itself, characterized by the unabashed celebration of… anything, so long as it has something to do with drinking, drugging, and prostitution. There isn’t a red-light district in Miami—it’s a red-light city. I saw a dude bounding down the street one evening effortlessly balancing a full martini glass between his fingers. Miami is his spiritual home. (Also: respect.)

In the midst of it, the city is at its bursting point with regard to services, traffic, and infrastructure; getting into the swing of things, I might have, on occasion, taxi-diven ahead of others and cut a few bathroom lines. Having thrown manners by the wayside, I should bone up on my Emily Post-etiquette before I inevitably return—I can’t not, but Miami will bring out the worst in you, and swiftly. It’s also the only fair with an accompanying outdoor soundtrack blaring (from somewhere) 24/7, the result of a relational aesthetics performative act no doubt. I’m bringing my own noise-deadening acoustic gear next time.

What can’t be dismissed is the beauty of the sea, the beach, and how medicinal a morning meander can be. As the ancient Greek Peripatetic school knew, there is much to be gained from a brisk stroll and the serendipitous encounters to be had with other art-worlders. There was Jeffrey Deitch, who I’ve bumped into while jogging each of the sixteen years of my attendance, though this go-round we were both reduced to walking—him because of an injury, me due to life. Jeffrey approached me and said I “deserved an award for my frank writing,” which was beyond generous coming from such a venerated vet.

Then there was a young, trendy dealer lamenting that he was demoted to participating in one of the (many) ancillary fairs, having been closed out of the main event due to petty politics and greed. He related that a dozen galleries in the Basel fair were pursuing a star from his stable of successful artists; without access to the slate of Basels, his relationships were jeopardized and he was exposed to poaching. Speaking of exposure, in all my Miami years, I’ve never once set foot in the ocean—it’s one thing to walk with your professional peers, but an altogether different thing to disrobe in front of them.

It’s a lot of work to trawl the fairs for print, systematically roaming the aisles like an automated fruit-picker and plucking what’s salient—requiring a kind of on-the-spot decision-making that’s comparable to a reading comprehension test with objects. There were certainly discoveries at hand, but there was also further evidence that the onslaught of these events has culminated in a sharp falloff of onsite gallery patronage and given rise to what I call tentism: a truncated attention span, shaped by the pop-up phenomenon of art fairs, that has forevermore rejigged the process of experiencing and consuming art. All the same, I was determined to look past the enormity of the money-mania and hunt for some insight, even wisdom, in the saturnalia.

Prior to my search for signs of art-fair intelligence, however, I’d be remiss not to at least touch upon the inimitable Miami nights. A friend plus-oned me to a coveted dinner at a private collector’s oceanfront penthouse, but before I could go I nearly had to sign a non-disclosure agreement; in the end, it sufficed when I swore on my kid’s lives to keep taciturn. The latecoming invite specified what turned out to be an incorrect address, which sent us on a wild goose chase for an hour and a half. We were assured this was an inadvertence, but you don’t have to be (too) paranoid to smell a ruse to keep me at bay till some of the boldfaced names had departed.

On another evening, I dined at a private club with some dealers—hardly the calmest or most patient lot, to be sure—one of whom marched up to the (not insubstantial) security cordon and barged right through it, ignoring the bewildered clipboard-wielding staff and huddled crowd of guests waiting in line, proclaiming, “Monsters! Monsters! Go away!” Cringing, the gallerist’s daughter accompanying us dropped back a few steps to dissociate herself from her errant parent, rolling her eyes to the point I couldn’t see her pupils.

Clamoring to get into dinner, Miami-style. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I must admit, some of the people aboard for the festivities would give a bona fide alien a run for their money in the strangeness department—and I couldn’t invent vocabulary to describe the less-than-there, garish outfits adorning all manner of sexes indiscriminately. The group I was with had their eyes elsewhere, on the phones in their pockets. When another of the dealers at the table received a call that a significant piece had presold before the fair’s opening, a sense of relief pervaded the table like a valve had opened.

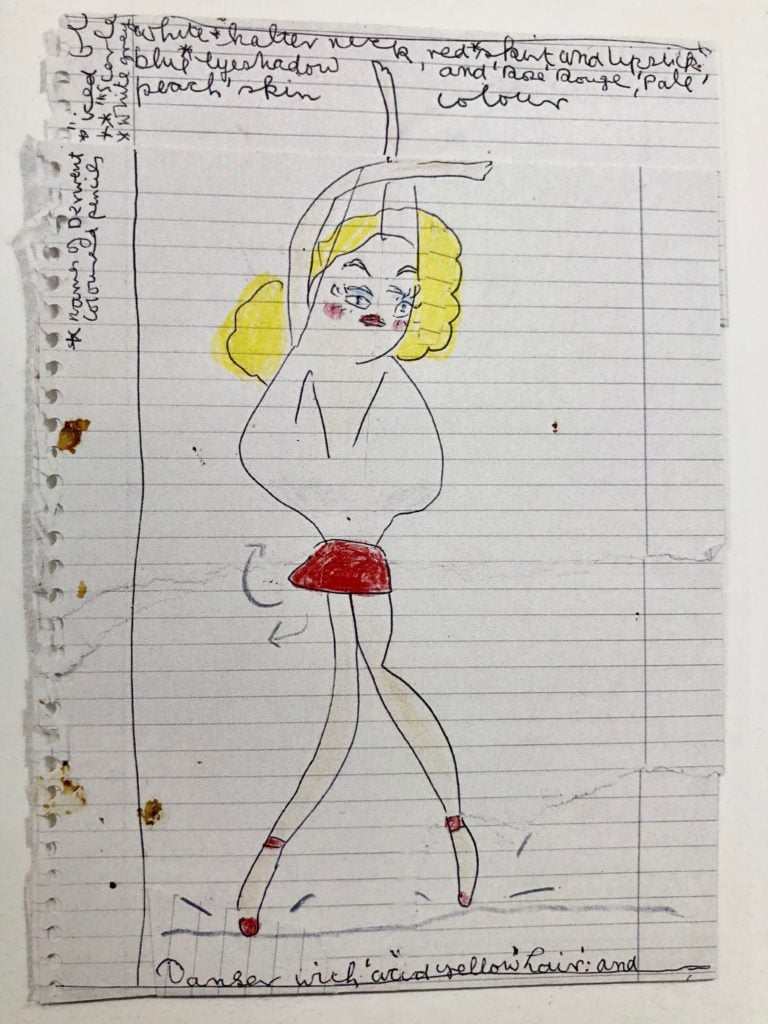

A Rose Wylie painted collage at Choi and Lager, who could resist? Not Kenny. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

There is not much to say about the Untitled Art Fair other than that it’s consistently inconsistent, with less quality offerings than NADA, but better than Scope. In spite of this, I breached my own self-proscribed no-buying pledge within 30 minutes—but, c’mon, a tiny Rose Wylie collaged painting on paper at Choi & Lager (Cologne/Seoul—today’s art world!) for under $5,000? I’m only human. Wylie, subject of an absorbing Serpentine exhibit in London, describes the ragged scraps of painted canvas (or paper) that she collages onto her works as “stickers”; in essence, she’s pasting over her hits and misses, leaving the traces satisfyingly visible.

I didn’t bother opening the torrent of PDF previews in my inbox, out of laziness coupled with the desire to be surprised. Basel likes collectors to enjoy this kind of serendipity, with the prospect of discovering something on offer at the fair—which is why, I heard, a highflying dealer was scolded for selling too much of his booth pre-fair, given an order to cease and desist. Immediately upon entering any town hosting a big event, you can feel a power physically pulling you to the halls, like an otherworldly energy—which dissipates just as quickly after opening day. I’m pretty confident art is the only business where you can spend infinitely (we’re talking hundreds of millions of dollars) without so much as a contract, lawyer, or even a pen, for that matter. You need simply utter the magic words, “I’ll take it”—even a mere “okay” will do. Often without a handshake. Think about it too much and you might break out in a cold sweat.

I never go to the initial onset of the VIP opening for fear of encountering tetchy rich people, who are more daunting even than my bulldozer of a dinner companion the other night. When I did enter the entirely newly configured halls, it was like encountering a mass of chickens nervously clustering in a new coop before pecking each other’s eyes out from misplaced fear and aggression. Once you fanned out from the main entrance, the crowd evaporated. As regards the new layout, intended to be more spacious and accommodating, I found it confusing, but then again I get lost in a supermarket (or on a straight line). Coupled with my pathological fear of getting lost, this is not an ideal combo.

One dealer (who I admire so much I can’t mention her) said the practical effect of organizing the fair around two central squares, which was the key design innovation this year, benefited some at the expense of others. There was a wrong side of the tracks, in other words, dictated like much else in the art world by the cold reality of hard economic hierarchies. Contributing to the maddening difficulty of navigation were the unaccounted-for inconsistencies in the alphabetical and numerical booth-identification system. The letters didn’t follow any logical (or alphabetical) progression—what was that all about? Perhaps the hope was that, with a diminished sense of orientation, off-balance bigwigs might drop a hundred grand in a blink of an eye—a MCH (Basel’s parent company) version of mind-control?

On opening day, at 10:30 am (the fair kicks off at 11 am), Larry G. and other heavy-hitting gallerists were refused entry to the fair by the fire marshals, the equivalent of the UK’s health and safety. Like an instant urban myth, word spread virally that the authorities were there because someone had been run over by a forklift, with the victim even identified as a union worker. Art Basel’s global director, Marc Spiegler, shot down this version of events so ferociously when I bumped into him on another early-morning walk that I’d almost gather it was true. Oh, I’m kidding Marc—no phone calls please. He said it was merely a case of some vehicles blocking a loading dock, nothing to see here, folks.

At first blush, most Basels smack of the latest Middle East shopping mall, drenched in cash, showcasing slick and soulless branded wares. A little digging on the fringes (where more emerging material is situated) rectifies that, offering up all kinds of finds for one’s delectation. The enormous, very cool Lucy Dodd abstraction that was leaning against the wall at New York’s David Lewis sold for $125,000, out-Schnabeling Schnabel. Another dealer pitched an artist as “black Julian”—what the fuck kind of a world do we live in? Don’t answer. Also, bringing internet art to a more sculptural and satisfying visual manifestation than the norm, the tech sculptures of young artist Yuri Pattison stood out at mother’s tankstation (located in Dublin, with a new outpost in London), priced between €5,000 to €13,500.

At Barbara Gladstone, there was a dizzying R.H. Quaytman abstraction for $200,000, a Richard Prince early fashion photograph triptych for $375,000, and a Mike Kelley Memory Ware for $3,100,000 that sold at auction in 2015 for $3,070,000 (meaning somebody wanted out pretty badly). None of the aforementioned works were sold towards the end of the first day. When I revisited the fair later on, which is always like seeing it anew, the Kelley had been moved to another wall—maybe a feng shui maneuver in the way I sometimes shift the furniture around in the hotel rooms I so frequently find myself in.

Pick a de Kooning, any de Kooning, yet one is nearly 4x the value of the other, even if the same size and same year (1977). Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

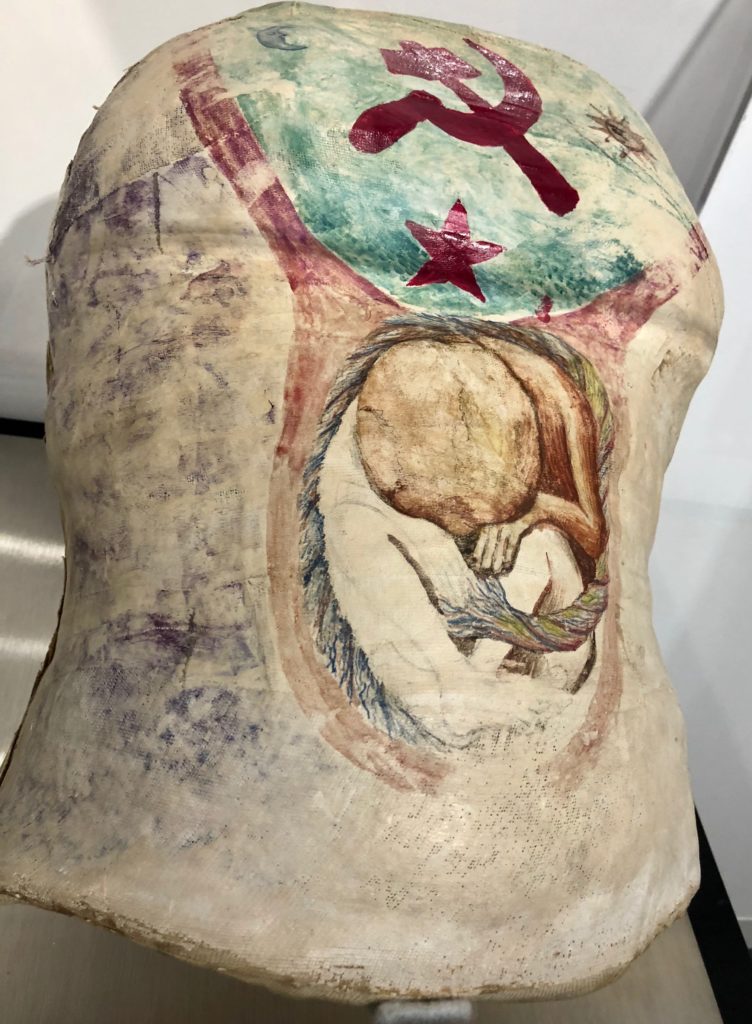

There were two de Kooning paintings of the same size (54 x 59 ½ inches) and year (1977) that ranged from $9.5 million at Edward Tyler Nahem to $35 million at Richard Gray Gallery. The superiority of the Gray painting was unassailable, but it was still of interest to see them under the same roof—the art-world version of comparison shopping. Francis Naumann, a relic from a time past when historical connoisseurship counted, had another kind of artifact for sale: the painted body cast of Frida Kahlo for $2.8 million. (Naumann related that the seller had turned down $1.8 million offer from Madonna.)

Frida Kahlo’s enormously expensive enormous body cast, circa 1950. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Like a character who stepped out of an Eric Fischl painting, replete with oversized houndstooth blazer, Mary Boone implored me to offer on her Mass Bass “Bloomingdales” painting in a tone between purring and threatening, with an asking price of $70,000—insisting she’d make it happen, a cross between a seductress and a mafioso. The Nahamds sold a Picasso for $22 million and rather than rejoice, sigh in relief, or raise a toast, half of the family was pissed off they had to part with the treasure. I worship art, it courses through my circulatory system, but not many are more obsessed than the Nahmads.

Mary Boone. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Hello! Welcome to NADA, the friendly fair where salutations are the norm and everyone appears chirpy despite the fact that my non-walk-in closet was bigger than some of the booths. But make no mistake, the struggle to sell is as much of a hustle there as anywhere else—witness the following text: “Hi Kenny, how are you! In Miami? I’m on the plane Miami bound, heavy turbulence so thought I’d send you our NADA preview here and now in case I won’t make it.”

I was jolted in my tracks (literally) when I stumbled into the booth of Chicago’s Shane Campbell Gallery to find the principals and staff fully clad in Adidas suits. Shane, you’re stealing my act! For better or worse (and worse), I’m kind of known for rarely removing that polyester wonder garment—it’s so perfectly built for comfort—and I’m glad I could be an inspirational force for team Campbell. The fashion statement, or lack thereof, did not deter buyers who bought nearly the entire booth, including a gelatinously painted interior by Alex Becerra.

The Adidas athleisure team at Shane Campbell. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Joel Mesler, the artist/dealer owner of East Hampton’s Rental Gallery, was pressed into having to personally lobby every selection committee member to coerce them into letting him represent his own paintings—which sold out between $6,000 to $12,000 to the likes of Beth Rudin de Woody, who took the fair week as an opportunity to open a private museum in West Palm Beach that’s chockablock with art from across decades. (Not dissimilar to how I live, ha.)

Called the Bunker (aka Beth’s bunker), it contains a potpourri of objects not to be missed, put together by an omnivorous collector from the old school with a strict credo that is unmatched now: art for art’s sake and the benefit of the artists. Full disclosure: Joel will show my art this coming summer (and Beth owns a few of my works, though they’re not on view).

The Pae White sculpture that caused a moment of past-life regression. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I immediately fell for a Pae White wall piece consisting of a sandstone cube embedded with avocados that had been computer-rendered (what isn’t nowadays?) for $18,000 at Los Angeles’s China Art Objects. I consume so many of those fruits masquerading as vegetables, I think I was an avocado in my past life. With my luck, should that recur, I’d suffer the fate of being the avocado that landed in an art fair.

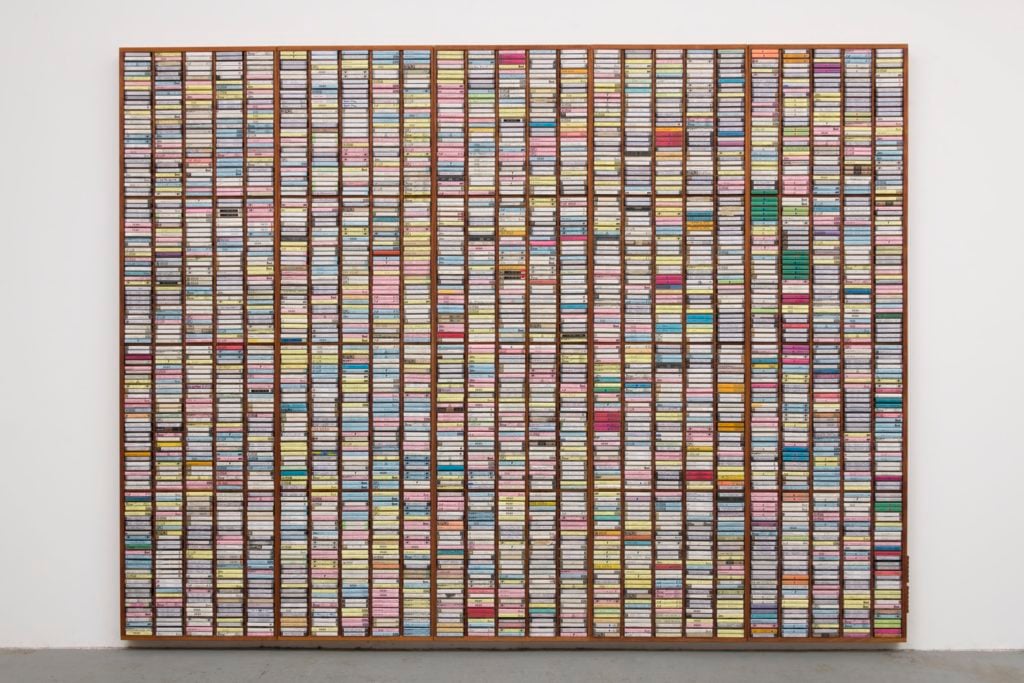

Paul Soto, a talented LA dealer, tried to sell me a great Mark Rodriguez work for $40,000, comprised of wooden shelving units housing hundreds of bootleg Grateful Dead audio cassettes acquired from eBay. In doing so, he assured me that Mark was in the collections of dealer David Kordansky and artist Mark Grotjahn. I’m not casting aspersion on the dealer, but I think we’ve entered a new universe where dealers and market-star artists are the conferrers of value rather than your traditional collectors, if they still exist.

For the Deadhead who has everything? Mark Rodriguez offered by Paul Soto of Park View. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Fairs are fungible yet simultaneously imbued with an identity of their own; the art does not vary nearly as much as it should—it is a business after all, and success affirms success—so you see a lot of the same stuff. There is endless noise about how visitor numbers and business compare to fairs past, but I can assure you that the numbers were at or near last year’s, if not a tad better. One could whine and moan till blue in the face, but it’s my lot to write about them (and, hopefully, yours to read my jottings) for as long as I could climb on a plane. And I’m not complaining, either. Art, even fair art, gives me sustenance.

I’d do anything for art, maybe even die for it—and I may one day, since a widely known, anger-management-challenged, very disgruntled lawyer recently told a friend that he wanted me dead. (Some people have no sense of humor.) Besides the homicidal lawyer, most of us get along, really; to willfully spend so much time together, we must.

Like another kind of relational aesthetics, what I gleaned from the fair, more than the art itself, was the nature of the interconnectedness of the participants, predicated upon mutual aesthetic compulsion and respect. Oddly, I’m already ready for more… though preferably without a blasting soundtrack in the background.