The live Instagram Stories that are proliferating under lockdown are the equivalent of anything-goes public-access television—an unprofessional stream of blather with horrible video and worse audio quality, not to mention the general banality of content. I’ve admittedly guested on more than my share of these broadcasts, and even staged an interview myself with British artist Tim Noble of Noble & Webster fame, who has since left that market-darling combo to essentially start over as an emerging solo artist. (Good timing.)

Today, May 5th, at 4 p.m. EST, I will make another contribution to the burgeoning muck-and-mirth genre with Irish artist Sean Scully—and, if you read my review of the BBC documentary on him, published a year ago today and quoting him as calling himself “the Donald Trump of the art world,” you can be certain it will be, um, spritely, at the least. The things we do to keep occupied during this seemingly interminable COVID crisis.

Sean Scully and me! Tuesday May 5th EST on Instagram Stories live; speaking of which, I hope I survive in one piece. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Since the earth stopped spinning on its axis and things took a turn for the… awkward, I’ve been living in a fog—literally, since every time I venture out in a mask my glasses cloud up. (As if I wasn’t dazed and confused enough already.) A few days ago, I felt like a character adrift in a “Twilight Zone” episode and actually had to google the day and date. Mainly, I’m at a loss as to how, when, and from where I will earn the next dollar or two now that my School of Visual Arts stint is over and selling art is only possible on a wing and a prayer, at least for me. You see, I’ve got no online viewing room to hang in (excuse the pun) and hawk my wares, though I did manage to sell one of my own artworks to a collector in Miami off Instagram for a not necessarily whopping, but much appreciated nonetheless, $6,000.

The More Things Change…

Art fairs? What art fairs? Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

On the bright side, ever since the end of the age of the mad rush, when everyone was racing nowhere fast, I’ve stopped bothering to wear a watch—it’s the longest I’ve stayed put in more than 20 years, and I’m glad to be off the treadmill of what artist Adam Pendleton called our “hurry-up culture” in a recent New York Times article. On the other hand, the art world, as resistant to change as ever, is still firmly stuck in its old habits, as in the case of spec-u-lector Jeremy Larner who spoke of selling off the younger artists in his “collection” in favor of buying more blue-chip works because “some of the emerging artists may no longer be in fashion.”

From bad to worse, Larner—who’s not a terrible guy, just probably in the wrong business—went on to recount flipping art bought directly from the Ghanian sensation Amoako Boafo, who he befriended (what are art friends for?), in order to buy works by Cecily Brown, Joan Mitchell, and Christopher Wool that he thinks he can resell at a profit. In his own words, told to Bloomberg: “I’d rather spend $1.5 million on an artwork than $60,000. It’s a safer bet.” I asked him to define what art is, but he couldn’t—for him, it may as well be widgets. To each their own, I guess.

Basel, Cologne, Brussels, Chicago, Buenos Aires, and a few others I am forgetting are musing about staging rescheduled fairs in early fall, not to mention Frieze and FIAC being slated as usual for October, which is at best wistful thinking—they should all make like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in the 1937 film Shall We Dance, belting out “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” on roller skates, and stop kidding themselves. I love patronizing art fairs as much as the next gal, but at the risk of death? As my kids would say, no thanks, I’m good.

MCH, Art Basel’s holding company, was teetering on the brink before the onset of the pandemic—I wouldn’t be surprised to see it shifted into the hands of a private equity firm. (Too bad the art-crazed Saudis are sitting on so much oil worth all of nothing today or I’m sure they’d have jumped right into that Messeplatz-shaped void.) The only viable art fair for the foreseeable future is one structured around acceptable social distancing, which rules out every convention center on the planet. They can always adopt the model of the Skulptur Projekte Münster, launched by Kasper König and Klaus Bussmann in 1977, where sculptures by international contemporary artists are spread far and wide throughout the city of Münster in public locations viewable on foot or by bike.

In an alarmist article on Artnet News last week penned by gallerist Magda Sawon of Postmasters, where I happened to have curated a 1992 group show on ethics (fitting enough) entitled “Morality Café,” the veteran dealer spoke of the financial crisis enveloping galleries worldwide, railing in a fit of hyperbole that “[t]he current virus may well be the equivalent of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Because sometimes, the system has to be destroyed in order to be liberated—and to make room for evolution.” I am afraid to say that, with all due respect, this is bullshit—or rather, in her case, a pipe dream. Granted, the hamster wheel has ground to a violent halt, the likes of which we have never seen before, ever.

But still, unlike anything else, art has the unique ability to satisfy all seven of the deadly sins in one go. And who is better suited to survive, and thrive, by serving them up on a platinum platter than the mega-biggies, Larry G., David Z., Hauser & Wirth, Pace, Lévy Gorvy, and Acquavella? And as troubled as fairs are, they’ll fare fine in the long run, also contrary to Sawon’s beliefs (or hopes). Don’t shoot the messenger.

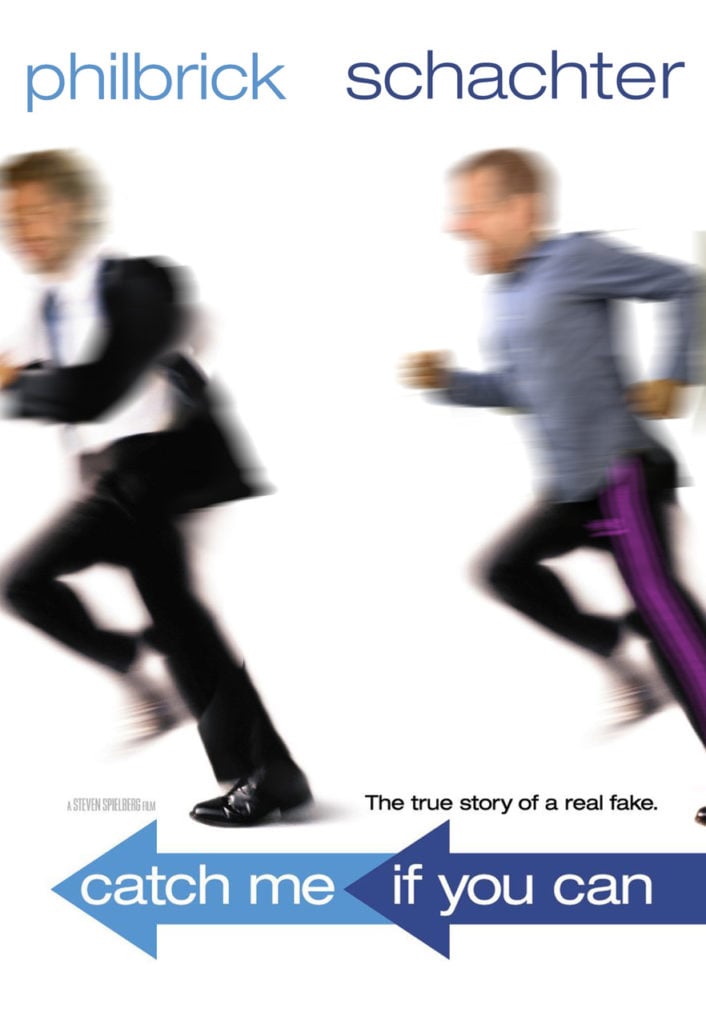

Its abundantly clear that we inhabit an art world rife with hypocrisy. I can’t complain, it fuels my writing, and I’m not above admitting to a certain degree of complicity myself. In that regard, next week will see another kind of auction—that for the movie and documentary rights for my New York magazine article about the epic alleged (by me and everyone else) art fraudster Inigo Philbrick. But I digress.

Getting much closer to a theater near you! Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The “Banality” Bailout

Back to non-me-related news, here’s a sobering eye-opener regarding the practices of another bloated art business, that of Jeff Koons LLC, the art-star enterprise long linked to the Mnuchin family, with Koons having exhibited at Bob Mnuchin’s gallery at least six times since 2001.

According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, headed by Bob’s son Steve Mnuchin, “the Paycheck Protection Program established by the CARES Act, is implemented by the Small Business Administration with support from the Department of the Treasury. This program provides small businesses with funds to pay up to 8 weeks of payroll costs including benefits. Funds can also be used to pay interest on mortgages, rent, and utilities.” And guess who is said to be the recipient of just such payroll payola? None other than Jeff Koons, an artist personally worth hundreds of millions of dollars, who is well known for replacing as many of his employees by robots as (post)humanly possible.

Koons’ studio spokeswoman has yet to respond to my email query at the time of publication, but several past and present employees have personally related to me that Koons is mean and mercurial and hasn’t raised wages in at least four years. In other words, don’t be fooled by the sweet saccharine platitudes that pour from the artist’s mouth for the media, preaching cultish gobbledygook drivel about happiness and transcendence that obviously doesn’t apply when it comes to his own staff.

In conclusion (for now anyway), I can’t really complain about much other than the financial insecurity. Thankfully my son Adrian has recovered from his six-week battle with a light case of corona, and I’ve been catching up on years of missed sleep, and I’m no longer the TV and movie illiterate I once was. Since the administration keeps harping on the notion that the virus originated in a Chinese laboratory, I wonder if it was all part of a nefarious conspiracy to make the developed world more morbidly obese than it already is. Besides that caveat, who in their right mind is going to want to go back to the harried pace of the past?

I’m kind of getting used to going nowhere fast, or rather slowly. Call it turtling. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I will particularly miss my weekly SVA class, which acted as a steady signpost in an unclear, uncertain world—something to look forward to, to organize my life around. Though I almost quit the day before it began in the midst of the pandemic—I’m hopeless at technology and had an acute case of zoomaphobia—it was just about the best art experience I’ve had to date. By the way, here’s the short essay I wrote for the Instagram show I curated as a gift for my students. And. on that note, I’m looking for similar such teaching work… unless SVA will have me back next semester, whether in class or in the ether.

Some Parting Words

SAVE STRENGTH

Use weakness as a way to people, not strength.

It’s a way of moving

I want to cry, but keep laughing.

– Paul Thek’s sketchbook, page 1969

In these tragic times, where we exist under a global lockdown, in an unprecedented state of fear (even more than usual), with countless lives prematurely lost, Paul Thek and his notions of art are more relevant than ever. Yes, we are universally compromised, but out of the heartrending upheaval and sickness the stream of creativity continues unabated (or, at least, only partially abated). The Instagram show of the School of Visual Art students from my senior studio workshop is proof that, despite the COVID-driven cancellation of their final academic exhibition, we can still wend our way to an audience.

Though Instagram and online viewing rooms are in general a (very) weak substitute for looking at art, to quote Malcolm X: “By any means necessary.” The SVA students’ works were crafted in bedrooms, in hallways, in showers, and on stovetops (literally) but nevertheless were completed despite the students being robbed of physical studio space. In art schools 20 years from now, I can imagine an assignment simulating quarantine and forcing students to make do with nothing more than what surrounds them at home. The art they created is characterized by love and blind faith—conviction and devotion make for some mighty effective art supplies.

This class has been a revelation for someone like me, mired in the daily machinations of fairs, auctions, and the market in general. Being self-taught (in what, don’t ask), this is the first studio class I’ve ever been a part of, let alone taught. Typically, in the art business, no one wants to hear about art, only who’s buying, selling, and showing it. I will surely miss the class and students and hope it won’t be the last.