Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

I’m a video artist who often incorporates popular music into my work and have been concerned about the degree to which Dua Lipa has been sued for copyright violations lately. Can you give me any insights regarding her lawsuits, to make sure I don’t end up in the same boat?

The accusations against Dua Lipa have something to teach us all. Indeed, Slate has called it “the most polarizing music copyright case since the court ruling on ‘Blurred Lines’ in 2015 (upheld on appeal in 2018) that cost Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams $5 million for plagiarizing Marvin Gaye’s ‘Got to Give It Up.’”

If you click through to that story, you’ll see a side-by-side analysis of the hooks and cadence of Lipa’s song “Levitating” and reggae act Artikal Sound System’s “Live Your Life.” They look, well, pretty much the same.

This is particularly incriminating considering the “Blurred Lines” case wasn’t anywhere near as concrete. Thicke and Williams said that while they were inspired by Gaye’s vibe, they wrote something new that shares no melodies, chords, structures, or lyrics with the original song. And yet: they still lost.

This was revolutionary because a feeling is very hard to pin down—and Dua Lipa has a lot more than a feeling at issue in the case against her. You should know, however, that the amount that one can borrow from a work varies depending on the medium. When it comes to novels, you may borrow the plot, setting, and characters of a previous work, so long as the point of the book you produce is to comment on the first. Whereas on YouTube, you might find yourself in trouble over a thumbnail.

You don’t have to worry about the issues concerning Dua Lipa because you’re working in a different medium from the people you sample—and visual art is especially liberal on these matters. So the next time you find yourself muttering, “How does he keep getting away with it?” when Jeff Koons beats another plagiarism accusation, you should count yourself lucky that you work in one of the mediums that values freedom of expression as its first principle.

People visit a McDonald’s before it closes at the end of the week as the company prepares to suspend operations in Russia, on March 9, 2022. (Photo by Konstantin Zavrazhin/Getty Images)

I’ve heard that Putin has allowed Russian citizens to steal intellectual property as retaliation for sanctions against the country. How is that possible? What about international copyright law?

It’s more than possible—it is already underway. Perhaps you’ve heard about the new Russian restaurant Uncle Vanya, whose logo just happens to closely resemble the trademarked one for McDonald’s? The fast food joint is set to replace McDonald’s proper, which pulled out of the country following the Ukraine incursion, and not everyone is lovin’ it.

Your question raises the issue of “international copyright law.” I am sorry to report that no such thing exists. Copyright law is specific to each country. Nevertheless, 180 countries have ratified a treaty known as the Berne Convention, which sets minimum standards for the protection of creators’ intellectual property rights. The Berne Convention was first signed by several European nations in 1886; America was very late to the party and only adopted it in 1989. Perhaps surprisingly, Russia itself became a member several years later, in 1995.

Berne signatories work with the international arms of local copyright authorities to prosecute reported violations in their own courts. Very few countries aren’t signatories, so when we say copyright protections are weak in countries like Russia or China (also a Berne member), we mean that they aren’t doing much to enforce the convention within their borders.

I recall reading Armando Iannucci’s ambivalence about his brilliant film The Death of Stalin (2017) being banned in Russia, because that certainly wasn’t going to stop people from seeing it in the pirate-rich country. If anything, news of the ban promoted the film better than any marketing campaign ever could. “Someone tweeted me a photo of himself watching it on a laptop in Red Square, right under Mr. Putin’s office window,” Iannucci wrote at the time. “I admired his chutzpah, but since he was downloading illegally, I also immediately reported him to the authorities.” Iannucci’s joke points to a real truth: while Russian civilians are subject to draconian laws and regulations, their I.P. is simply not protected.

Still, a fire sale on I.P. in Russia is a weak response to Western sanctions. All it really means is that they’re loosening laws that weren’t that impressive to begin with. It’s really the McRib of retaliations: overhyped and motivated by market conditions.

A scrap dealer in India pushes his handcart past NFT graffiti. (Photo by Ashish Vaishnav/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

I was hired to make art that will be part of a larger NFT project. I can charge my client the way I normally would for a commission where I get a one-time payment and my client can use the work as they please, but I’d like the benefit of the NFT! Can I ask for a percentage of the sales or a royalty or something like that?

Indeed you can. What you’re describing is the inclusion of resale royalty and it is one of the aspects that makes me most excited about NFTs.

When an actor appears on Law and Order: SVU, she’ll continue to receive residual checks for that appearance for as long as she keeps her address current with her agent. These sums might not be much, but even if she just played a body stumbled upon by a couple coming back from brunch, it’s both nice and appropriate that her contribution is acknowledged every time the episode airs.

Artists, on the other hand, do not receive any kickbacks from subsequent sales of their work in the United States. (It’s a different situation in other countries.) Legally speaking, this is called the “first sale doctrine” and, given the staggering sums achieved for art at auction, we at ARS feel this is wrong. Indeed, we lobby Congress, frequently, to pass a bill that would give a percentage of those sales to artists.

Now, NFTs have begun to show us a solution through the private sector. Through clauses written into the baseline code of the NFT, creators can be ensured that whenever the work is resold, a negotiated percentage of that resale price automatically goes back to them. The blockchain is, more or less, a public ledger, so even though there are still technically ways to cheat the system and get around paying these royalties, the market can discourage it through blackballing of bad operators.

Remember, this technology is still extremely new and therefore can be faulty (interoperability amongst different platforms is a particular point of contention for many creators). That said, it is very exciting that it may become easier for people like yourself to be paid what they’re owed.

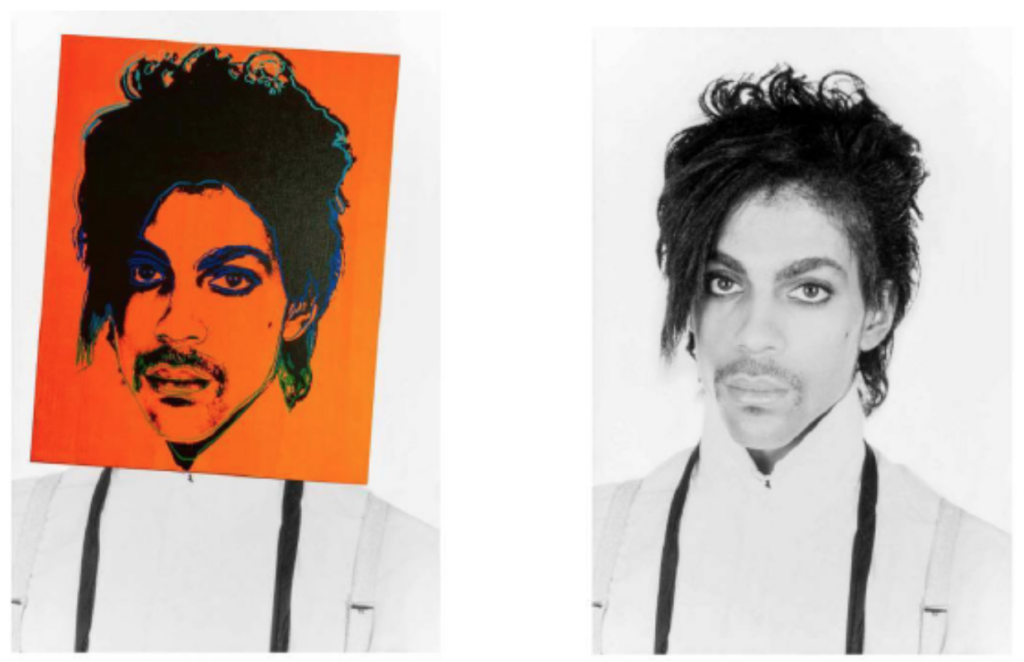

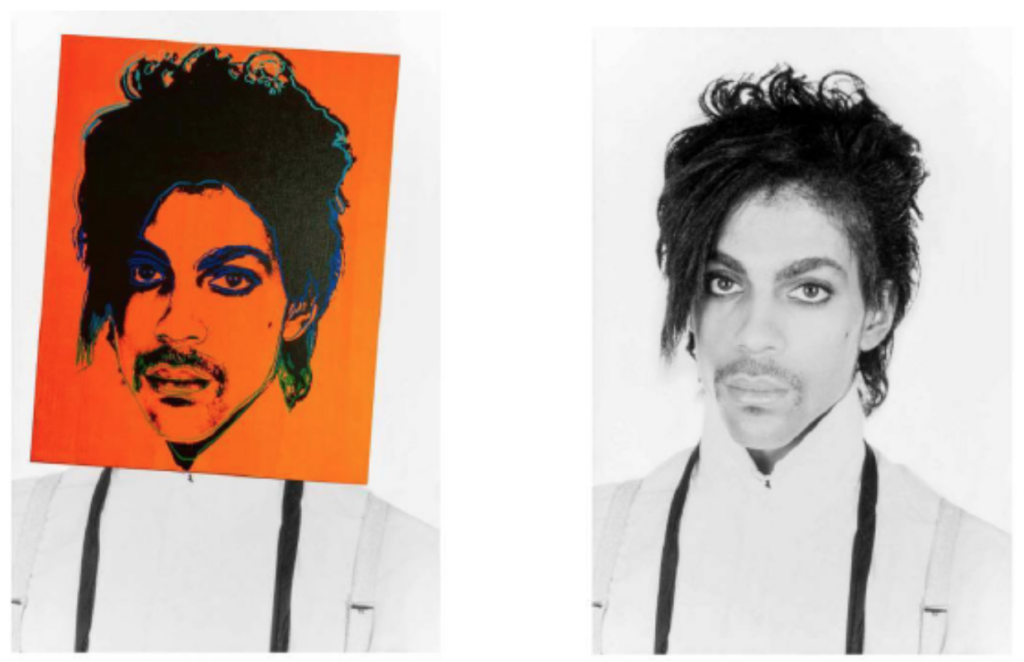

Andy Warhol’s Prince portrait overlaid on top of the original Lynn Goldsmith photograph of the musician, as reproduced in court documents.

I read that the Supreme Court will soon hear a case involving Prince, Andy Warhol, and copyright. I’m not sure if I understand any of those three entities, but I do know the Supreme Court is important, so can you please break down why this case matters for artists?

I admit a degree of bias in this case because the Andy Warhol Foundation is a longtime business partner of my firm. But they’re the side to support if you’re an artist because what’s at stake here is something I referenced earlier in this month’s column: the ultra-protected nature of art, as a medium, when it comes to fair use. This case, the foundation wrote in its petition to the Supreme Court, “threatens a sea-change in the law of copyright” and “casts a cloud of legal uncertainty over an entire genre of visual art.”

The background for the upcoming Supreme Court hearing dates back to a 2021 ruling in the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals that overturned a 2019 decision concerning a 1984 Vanity Fair commission made by Andy Warhol. Warhol based his painting on a 1981 photograph of Prince taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith that the magazine had licensed. There was just one problem: he ultimately made 16 different artworks from the photos, which Goldsmith only learned about in 2016, the same year we lost The Purple One.

The implications are as vast as the foundation says. Just cruising through the website for the recently opened Whitney Biennial, I see a couple of trademarked logos, a work that references a major Hollywood franchise, and another that mimics the design of something that is patented. To open up all of these works to potential lawsuits would be a tragedy. We won’t know what a ruling in favor of Goldsmith would mean for these works until it comes down, because it will all be in the wording, but I chose the Whitney Biennial because it’s a survey of contemporary American art. To make art today is to engage with the broader culture, and increasingly that culture includes intellectual property.

While I feel for Goldsmith, I do believe she is in the wrong. Her photograph of Prince was an attempt to document the man and the complex mix of eros, power, and vulnerability that went into his personality. Warhol’s celebrity portraits, on the other hand, are about the sociology of celebrity. “Elvis Presley existed not only as a flesh-and-blood person, but also as millions of pictures on album covers and movie screens, in newspapers and magazines. He was infinitely reproducible. Similarly, using the silkscreen printing process, Warhol could produce as many Elvis paintings as he pleased.” That’s from a lesson guide for children at the Warhol museum, which I quote here in case anyone from the majority of the current Supreme Court is reading this. Even they should be able to understand that.