Opinion

Why the Passing of Interview Magazine and the Rise of Gagosian Quarterly Represents a New Era for the Art World

Some of the most inventive writing and ambitious art coverage is happening in the pages of art-marketing magazines.

Some of the most inventive writing and ambitious art coverage is happening in the pages of art-marketing magazines.

Richard Polsky

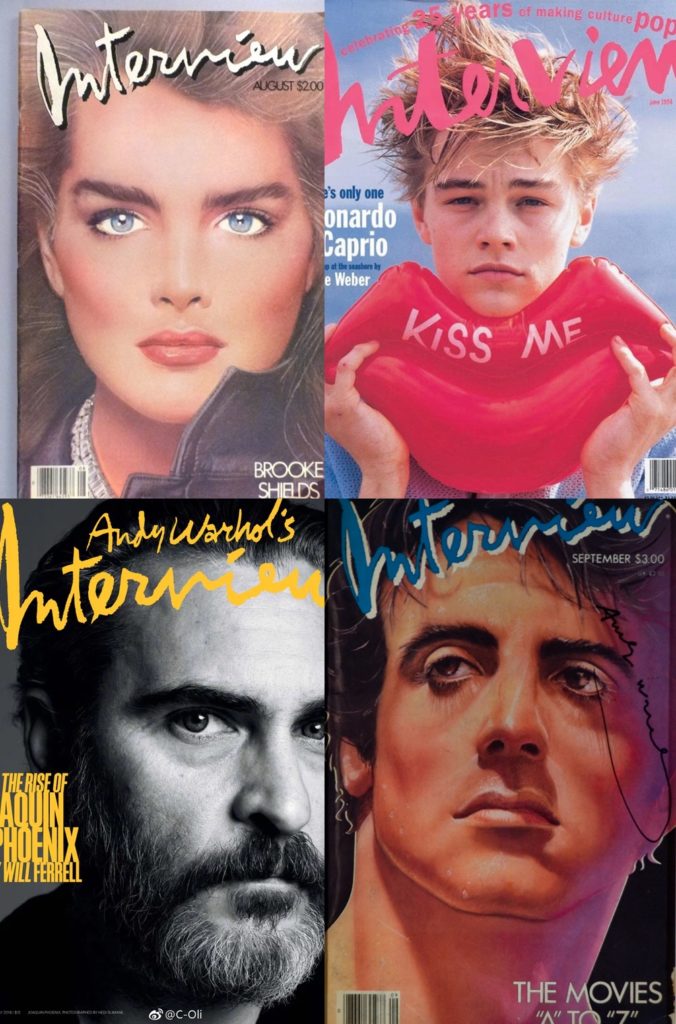

Officially, Interview magazine met its demise last month. But for all practical purposes, the magazine really folded back in 1987—the year that Andy Warhol passed away. Though Warhol’s name hadn’t appeared on the masthead for years, his ownership gave the periodical a hard-to-define relevance. Founded in 1969, its original purpose was to expand Warhol’s celebrity circle—all the better to secure portrait commissions.

During the 1970s, getting on the cover of Interview mattered to actors and musicians. By the 1980s, however, the world had moved on. Upon Warhol’s death, one of the smartest things his executor, Fred Hughes, did was to sell the magazine to Peter Brant in 1989 for approximately $10 million, according to the New York Times. It would never be worth big money again.

The strange thing was that Warhol failed to put famous artists on the cover. While he obviously had access to Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, he never sought them out, preferring the likes of Mick Jagger and Richard Gere. The point is that Interview never really mattered when it came to the art world.

When it recently folded, a lot of people connected to the art scene weighed in with nostalgic notes about how much it would be missed. Maybe that’s true. But the loss of Interview is nowhere near as important as the current struggles of the art world’s leading magazines, which include Artforum, Art in America, and ARTnews. Since I’m not their accountant, I have no idea what their balance sheets look like. What I do know is that they—along with much of print media—are in trouble in an existential sense.

A selection of Interview magazines over the years. Courtesy of Brant Publications.

It’s not so much that we now get most of our news from the internet. The issue is that art criticism has—in the process of becoming democratized on Instagram and abbreviated into tweet-size bites—lost much of its gravitas. If you go back to square one, art magazines hired critics and journalists to write serious discourses on the most significant artists and movements of their time. There was also plenty of politics involved. Though editors would swear until they were blue in the face that the galleries that advertised didn’t receive preferential treatment, when it came to reviews, we all know that wasn’t true. Like it or not, art magazines were (and are) commercial enterprises.

All of that aside, most art-world professionals have long been in agreement that, for better or worse, we needed all of the art periodicals. But now, collectors, curators, dealers, advisors, auction specialists, and even artists are ingesting a media diet that is far more diverse than three or four mainstream magazines. Two curators could read about art around the clock and still have little overlap in their media consumption. I would argue that because of this decentralization, and a host of other factors, the most relevant publications now are not independent publications, but major auction-house catalogues and—don’t laugh—the magazine Gagosian Quarterly.

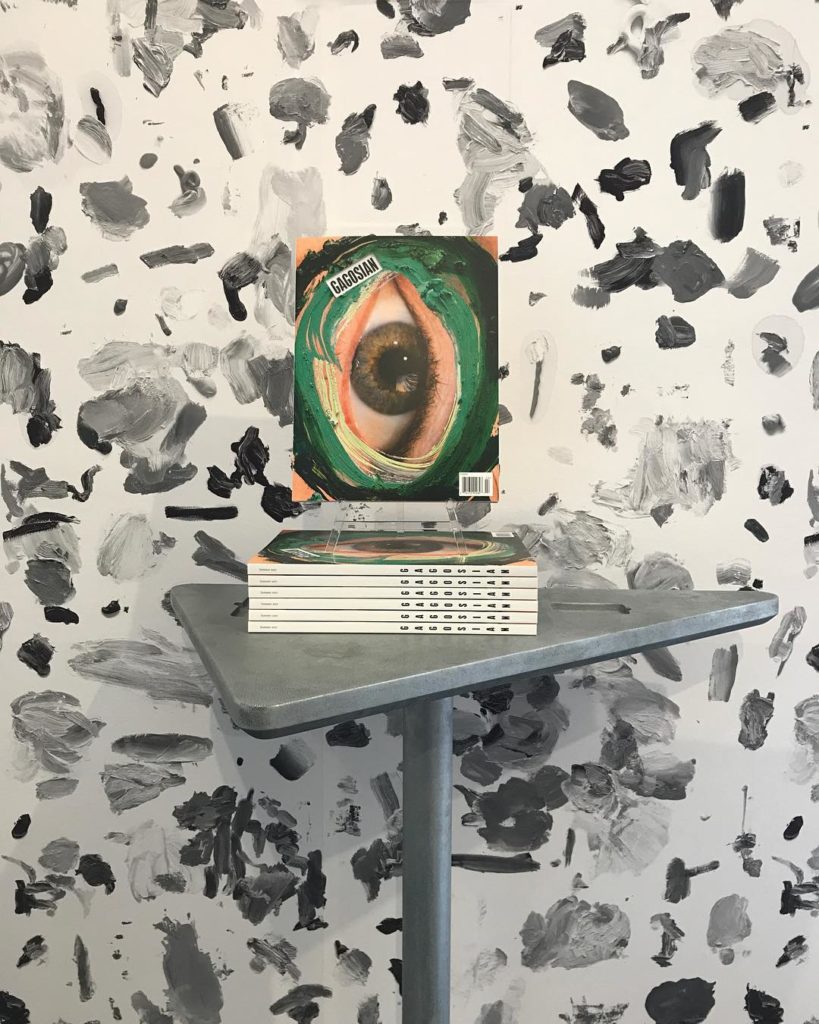

It may sound like sacrilege, but bear with me. In each case, armed with large budgets, these publications can afford to promote their commerce-oriented agendas. Traditional art magazines, no matter how large their circulation, were never in a position to pay their writers high fees, offer travel budgets, or illustrate their articles with the highest-quality photography and custom fonts. Auction-house catalogs and Gagosian Quarterly, by contrast, are able to tick all of these boxes—and do. In fact, Gagosian—the periodical launched by the gallery and fronted by Derek Blasberg—is now among the most widely circulated art magazines, with a distribution of 50,000.

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2017. Courtesy of Gagosian.

Since the end of the Great Recession in 2009, the art market has been on a steady upward trajectory. But at the same time, the latest wave of collectors has lost interest in art criticism. They may be information junkies, but the guidance they’re looking for is not about how David Hockney’s work evolved from paintings of swimming pools in Los Angeles to depictions of the Yorkshire countryside. They’re much more interested in short-term financial analysis—whether, for example, his pools are better investments than his recent landscapes—than in a far-reaching art-historical assessment of which series is more likely to stand the test of time.

That’s where Sotheby’s and Christie’s auction catalogues come in. Though many of us are fond of saying that you can get a hernia lifting one (and Christie’s has dramatically cut back on printing hard copies), these tomes are chock full of useful information about paintings and artists. Obviously, their illustrations and essays are geared toward promoting the specific works of art for sale. Yet, as I peruse these catalogues, I can’t help but find myself being drawn in. If you can get beyond some of the hyperbole, there is a surprising amount of pleasurable reading.

But the period at the end of the sentence on the evolution of art magazines may very well be the magazine Gagosian Quarterly.

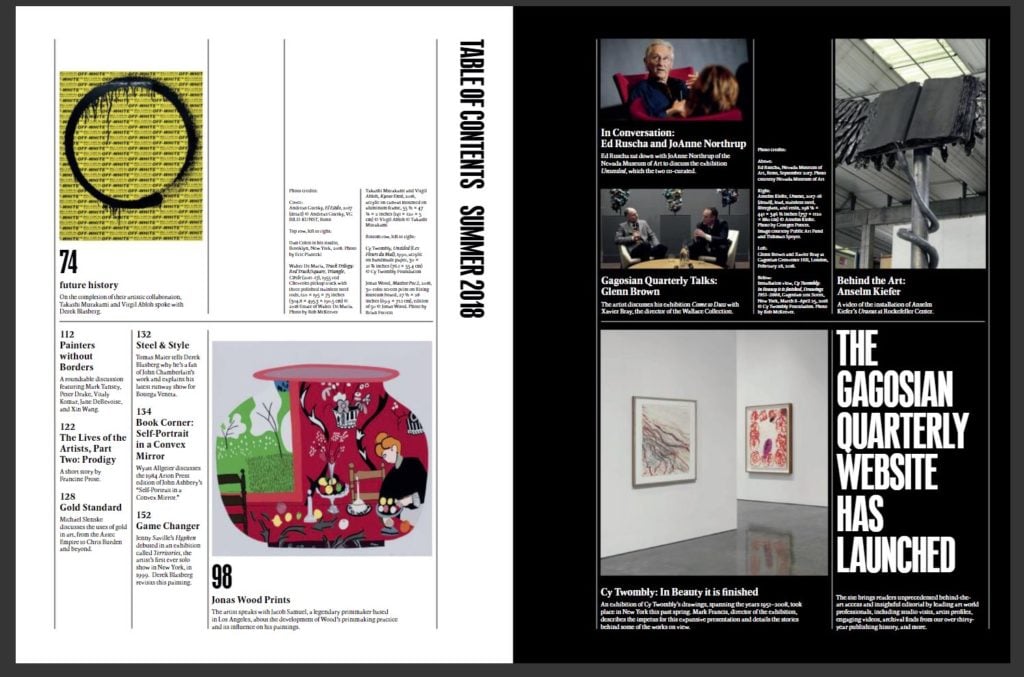

Screenshot of Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2018 issue. Courtesy of Gagosian.

I have no special attachment to the gallery, but I have to admit that its publication comes close to being a work of art in its own right. When my copy arrives, I enjoy pouring a glass of wine, putting on some jazz, and kicking back with the issue. Just like the auction catalogues, Gagosian has a purpose, and that purpose is to promote the gallery’s extensive roster of artists and its international brand.

A recent issue, for example, contained a lushly illustrated, engaging feature on a never-before-seen work titled Truck Trilogy by Walter De Maria, whose estate the artist represents. Written by Lars Nittve, the founding director of Tate Modern and an expert on De Maria’s work, the feature posits that the glossy 1950s Chevrolets symbolize the artist’s coming-of-age—”an American version of Proust’s madeleine.” Thus, in the interest of commerce, I learned about a major work of art that I never knew existed. (Other art magazines write almost exclusively about what dealers give them access to; Gagosian, on the other hand, presumably has all the access it wants to its own material.)

What I find fascinating is how the magazine has been able to attract high-profile advertisers from the world of fashion and luxury—just like Interview. What that means, then, is that luxury advertisers are paying to appear alongside another form of luxury advertising.

Make no mistake: Gagosian Quarterly is all about marketing. It tries to place the artists the gallery represents within an intellectual context, thus allowing both the talent and potential collectors an opportunity to feel good about their respective roles. The key here is transparency. Gagosian Gallery is clear about what it’s up to.

In a way, it’s no different than Hauser & Wirth’s museum-size space in Los Angeles, for which the respected museum curator Paul Schimmel temporarily served as a partner. In both cases, the galleries are making a statement: They want to bring a rigorous intellectual context to their program. Yet, despite the historical importance of the art they write about and exhibit, much of it is unapologetically for sale.

The art market has radically changed. There’s been an extreme blurring of boundaries. It’s now commonplace for museum curators to cross what had once been an inconceivable line and take a high-profile job working for a major auction house or a mega-gallery. It’s also not uncommon for a museum to lend a work of art to a gallery exhibition, or for a curator to write a catalogue essay for a commercial show. One of the world’s top art writers, Randy Kennedy, left the New York Times last year to join Hauser & Wirth to relaunch the gallery’s magazine.

Screenshot of Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2018 issue. Courtesy of Gagosian.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this. Everyone is entitled to make a living. The issue, which mimics the shift taking place within art magazines, is this: At a time when so many outlets are trying to play two sides of the same coin, projecting independence while courting advertisers, isn’t there virtue in well-funded outlets that are unapologetic and transparent about their goals?

Like it or not, the future of art magazines may look a lot like Gagosian: an amalgam of art, commerce, and lifestyle. I am sorry to say goodbye to Interview, and I sincerely hope that the “big three” art magazines stick around for a long time. But at the end of the day, I simply want to read something that inspires me to go look at great art in person and think big thoughts—and Gagosian Quarterly definitely does that. If you return to the true purpose of art criticism and its print vehicles, that’s what it’s always been all about.

And whether you are sanguine or saturnine about the direction of art writing, we can probably agree on one thing: We get the publications we deserve.

Richard Polsky is the author of I Bought Andy Warhol (2004), I Sold Andy Warhol (Too Soon) (2009), and The Art Prophets (2011). He is also the owner of Richard Polsky Art Authentication, which specializes in authenticating the work of Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Keith Haring.