Op-Ed

How a New Kind of Artist Contract Could Provide a Simple, Effective Way to Redistribute the Art Market’s Wealth

KADIST's new resale rights proposal could help artists take back their market.

KADIST's new resale rights proposal could help artists take back their market.

Joseph del Pesco

I wasn’t sure we were onto something until I learned that in 1992 artist Cady Noland, well known for her complex portrayals of a violent and divided America, once attached a contract to the sale of two artworks that set specific terms—if the work was resold, 15 percent of the profits would be sent to Partnership for the Homeless. What little is known about this contract suggests it was attached to two silk-screen prints. Fortunately Partnership is still running decades later, so if those artworks were resold today they would generate an unexpected donation to a deserving nonprofit. And as an incentive for going to the trouble, the (re)seller would be eligible for a tax deduction.

Starting around two years ago, I found myself thinking about artist contracts after the repeal of the California Resale Royalties Act (CRRA), a law that for more than 40 years gave California artists 5 percent of resale profits under specific conditions. It was the only such law in the nation, and the last vestige of a movement to address the inequitable distribution of wealth in a rapidly growing art market. If you’re an artist, you likely know: the first time an artwork is sold, the artist benefits, but when an artwork is sold again, only the seller benefits, not the artist. The movement sought to enable artists to preserve some role in the future of their artwork, to make it so that they might continue to benefit from their hard work on its behalf, and that it might retain some of their personal or political values after it leaves the studio.

Imagine a scenario where an artist is asked to speak at Museum X on behalf of an artwork they sold for $1,000 to a collector/dealer, who subsequently sold it to Museum X for $50,000. The artist, of course, received no portion of the $49,000 in profit generated by their artwork, and yet they are asked to act on its behalf (often for a small honorarium). This inequitable distribution has become so obvious now that over 70 countries around the world have added artwork resale laws to compensate artists.

Graphic for KADIST’s new Artist Contrat.

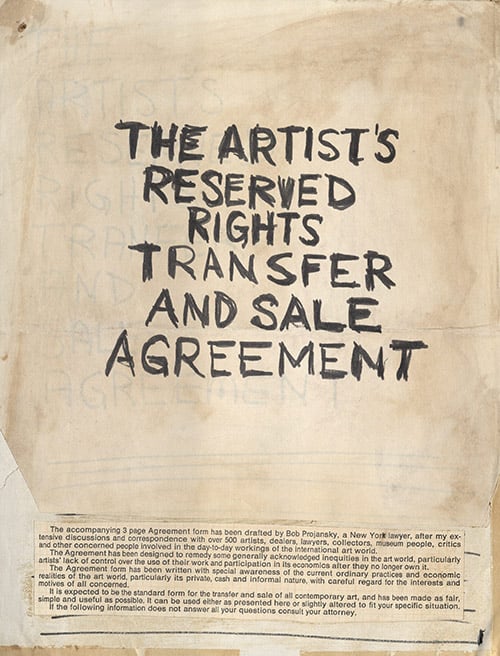

Losing the CRRA felt like a step backwards, for artists and for the arts. Because I work for KADIST, which has an office in San Francisco, I started thinking about the larger political implications, the backtracking of liberal gains. This led me to historical precedents, and the “The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer And Sale Agreement,” drafted by Seth Siegelaub and Robert Projansky in 1971. The contract emerged from conversations with groups of progressive artists, collectors, lawyers, dealers, and critics in New York City. In addition to resale benefits, the contract secured artists rights and controls over their work after its sale, some of which are now covered by the Visual Artists Rights Act, passed into US law in 1990.

A few months later, during a conversation with the painter Amy Sherald, I sketched out an idea for a new version of the contract. After getting the support of Lauren van Haaften-Schick, a historian who studies artist contracts and artists’ rights law, I took the project to another friend, a lawyer, collector and supporter of the arts, Laurence Eisenstein, who revised it for us, pro bono.

Mock-up draft of the Artist’s Contract in English (ca. 1971). Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Today, we have created a contract that enables an artist to designate a charitable organization to receive a percentage of the resale profit of an artwork. Accompanying the ready-to-fill-out contact, Lauren has written a deeply researched, long-form introduction detailing how our contract enables the “wealth created by the resale of an artwork to serve a general good, as a future investment in organizations that exemplify the values of the artist.” As in Cady Noland’s contract, an artist selects a nonprofit, names them in the contract, and if the work increases in value, a percentage of that profit is sent to the charitable organization as a gift, supporting their cause. We liked this variation because it addresses some of the criticisms of the Siegelaub-Projansky contract (that only successful artists benefit from its use), and that it redistributes wealth to produce social good, but the clincher is that it’s practical. Because the money goes to a charitable organization, the reseller gets a tax deduction when they make the donation, creating an incentive to follow-through.

Lauren and I recognize that many artists are resistant to the idea of introducing a contract during the process of a sale. Especially when there’s no gallery to work as an intermediary, negotiations can be delicate and confusing. We are betting that because of the tax deduction, the buyer will immediately understand they stand to benefit in the future (if they decide to resell the artwork), and that this will make it easier—and that tax-deductions are common enough in the arts to be non-threatening, even familiar.

Amy Sherald in her studio, 2019. Photo by Melanie Dunea, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

While I know many artists share the progressive social values of Cady Noland, and would happily see some ancillary benefit to the world produced by their artwork, this contract also suggests a less obvious possibility: artists can direct the resale percentage to a non-profit they start and run themselves. This is what I had in mind when I suggested the idea to Amy Sherald. She was considering starting a non-profit education program, and I thought that the resale of her artworks might provide a source of funding, eventually. Consider the millions that the Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Joan Mitchell foundations (to name just a few) have given to artists and arts organizations over the years. In this way, artists can both benefit themselves and the artist community.

The monetary impact of this contract wouldn’t be immediate. To see them, you have to peer into a world ten or so years into the future. And I know that taking the long view doesn’t come easily to anyone concerned about paying next month’s rent, nurturing the next opportunity, or fighting for visibility. But these unprecedented times can serve as exceptional ruptures in the status quo. With Black Lives Matter, and other activist organizations gaining momentum across the country, and the need for a sustained movement, not just starting (or putting out) fires in the present, this contract offers an opportunity to align future profits with your political and social values.

It appears that the two serigraphs associated with the contracts used by Cady Noland sold for $2,000 each in 1992. And in 2019, a serigraph of the same size (possibly a related print) sold at auction for $20,000. Now if we imagine a scenario where the two serigraphs listed in the aforementioned contract were sold today, they’d generate a $5,400 donation to Partnership for the Homeless. Zooming out, sales of art in the US reached $29.9 billion in 2018, and while the market has changed in recent months because of COVID-19’s impact on the global economy, we can expect that the circulation of incredible sums will continue.

Imagine if just 2 percent of that $29.9 billion did some good. That’s 600 million dollars reaching charitable organizations, about four times the yearly budget of the National Endowment for the Arts. Now imagine if that $600 million was controlled by non-profits run by artists…

The new contract is online, ready to fill-out and print at artistcontract.org.

Joseph del Pesco is the International Director of the KADIST.