Opinion

How Gen Z’s Meme Artists Are Reshaping the Political Battlefield + Two Other Illuminating Ideas From Around the Web

Plus, an epistolary exchange highlights the plight of Chilean artists and Art Spiegelman surveys the work of Rube Goldberg.

Plus, an epistolary exchange highlights the plight of Chilean artists and Art Spiegelman surveys the work of Rube Goldberg.

Ben Davis

Every week, we scan the media for interesting conversations about art. This week: the odd mutations of political meme culture, artists reckon with Chile’s political crisis, and assessing Rube Goldberg as an artist.

In recent years, starting with his cult text “Politigram and the Post-Left,” the New York artist Joshua Citarella has been digging deep into the political youth subcultures of social media and their astonishingly febrile twists and rapid mutations.

If you’ve got an hour and forty minutes to spare, it’s worth your while to check out this new podcast where Rhizome’s Michael Connor and Aria Dean interview Citarella about his research. Together, they recap an event at the New Museum in which auto-didact Gen Z meme-makers discussed the political dynamics of their work.

The discussion offers a glimpse of Gen Z radicalization and how digital cultures have unfolded under the pressure of increasingly inescapable political and ecological anxiety. In addition to eliciting delirious and nihilistic memes, the rapid flow of information has led to some astonishingly sophisticated examples of self-taught political theory that remixes and cross-wires theoretical references in unexpected ways.

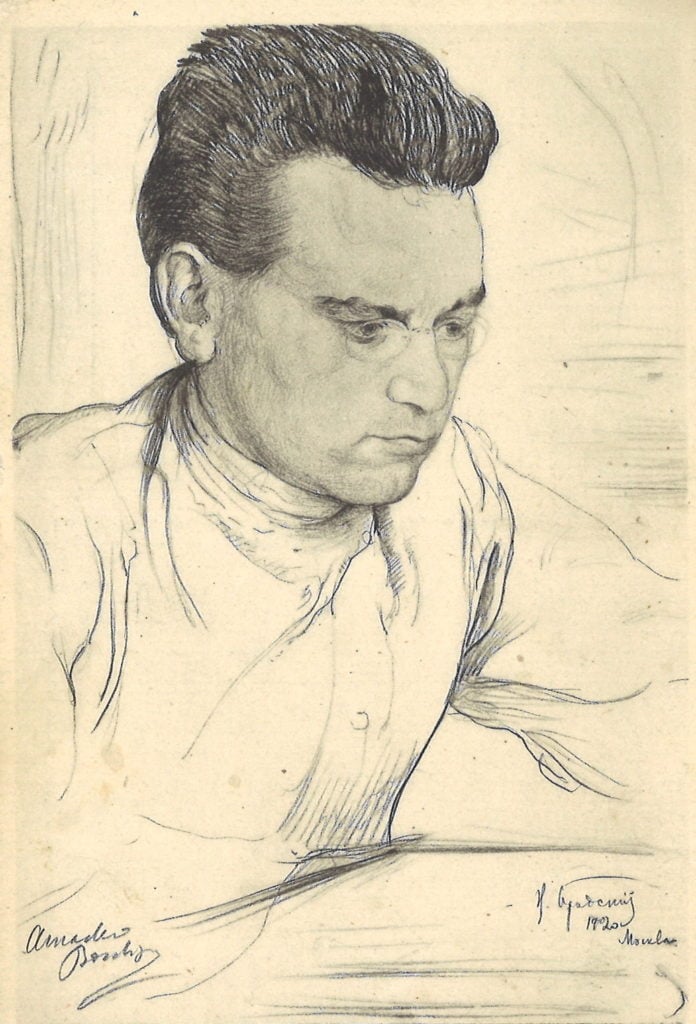

A 1920 drawing of Amadeo Bordiga by Isaak Brodsky.

This may take us too deep into political-theory nerd territory, but as an example of the new intellectual landscape, the podcast mentions that Italian Marxist Amadeo Bordiga is a hot reference. It also mentions that, by contrast, Antonio Gramsci—the Italian Marxist of choice for generations of academics, eventually watering down his important insights into the truism that “culture is a field of struggle”—is nowhere to be found.

Bordiga is most often remembered as a classic “ultra-left” figure, an inflexibly sectarian thinker whose strategy emphasized insisting on the rightness of his political line and its difference from all others. Gramsci, on the other hand, was the thinker of alliance-building who advocated building influence among blocs of forces through practical leadership in action.

What’s behind the newfound cachet of once-dustbinned ultra-left theory? Citarella suggests that it may be due to the sense of go-it-alone isolation produced by the combination of a keen sense of crisis and massive, intractable institutional inertia. But I wonder if it has also to do with the atomizing affordances of social media itself, which shape the terrain in favor of extreme phrase-making over the organizational alliance-building of Gramsci.

Just a thought! At any rate, there’s actually a hopeful current to the conversation if you stick around, with the suggestion that the meme-making politicos Citarella has been tracking—one of whom phones in to the podcast at the 27-minute mark—seem to be moving from online info-wars into more organized politics. It’s fascinating.

Demonstrators during a protest demanding social reform from Chilean President Sebastian Pinera in Santiago on November 12, 2019. Photo by Rodrigo Arangua/AFP via Getty Images.

Chile has been in the throes of an epoch-shaping political crisis since last year. It’s more than worth your time to read this brainy, heart-felt set of letters (published in the Mexico-based art mag Terremoto) between these two artists, which begins with a discussion of how omnipresent graffiti has transformed the literal political landscape of the country.

The epistolary exchange gives a lived-in sense of how dramatic times shift the stakes of art-making, throwing up new questions in dramatic new ways—albeit ones that might not have easy answers. “Unfortunately for the museum,” Ignacio Gatica writes, “what’s happening on the outside, and now literally on its outer walls, is once again more interesting than what’s happening inside of it.”

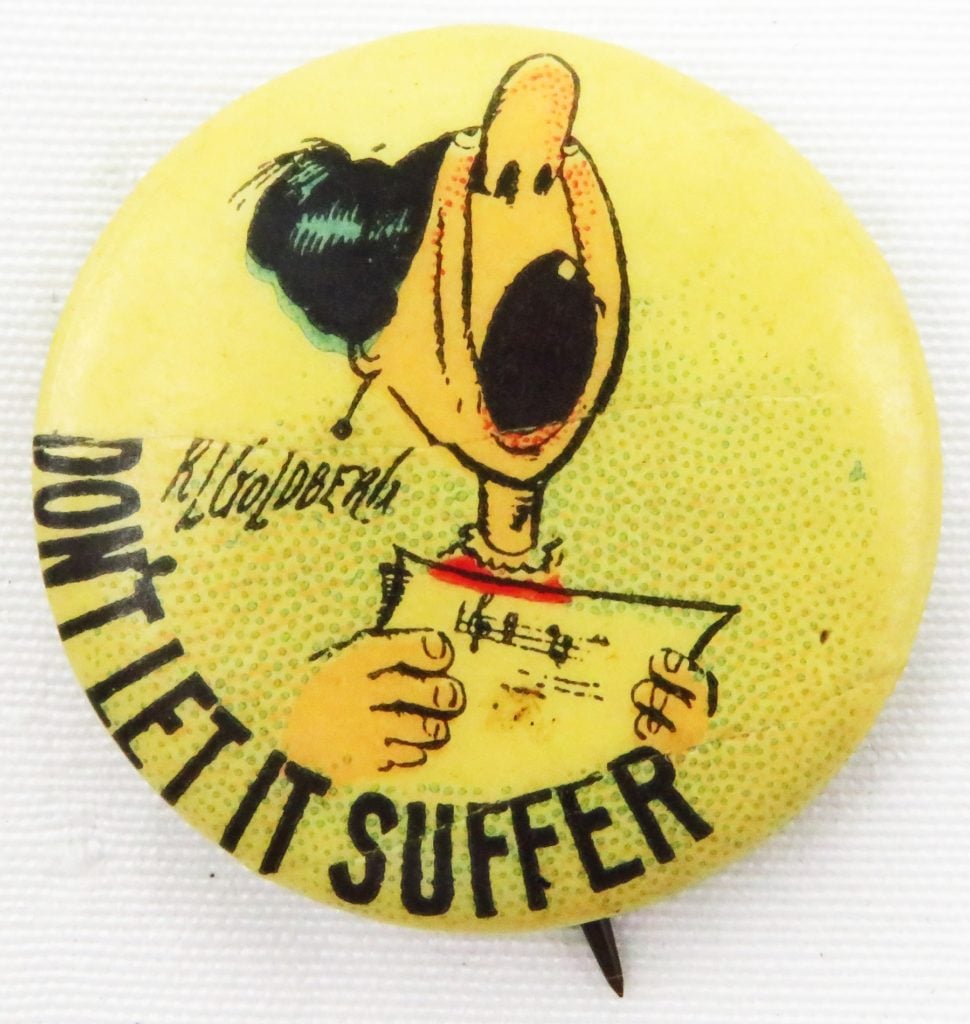

Anti-suffrage button with a Rube Goldberg cartoon satirically depicting a singing woman. Photo by Ken Florey Suffrage Collection/Gado/Getty Images.

Maus author Art Spiegelman gives a thorough walk-through of the life and art of Rube Goldberg (1883-1970), whose work was recently seen at the Queens Museum. Goldberg’s delightfully over-elaborate contraptions turn out to have been part of an international mini-movement of machine-age absurdism. (Also, it also turns out, he was anti-New Deal and pro-McCarthy.)

Stick around for the end of the article, which gives an overview of the history of the “screwball” comics genre through Spiegelman’s characteristically informed lens, giving a sense of both the medium’s dangers and its delights.