Outrage continues to radiate internationally over the detention of photographer Shahidul Alam in Bangladesh. I’m convinced, however, that if more people understood just how unique and vital a role he plays on the world stage, that outrage would be far greater still.

A giant of the photography world and a powerful social critic, Alam was detained on August 5 just hours after going on Al Jazeera and expressing criticism of the government’s handling of student protests in the country. He claims to have been tortured while in detention.

A 63-year-old native of Dhaka, Bangladesh, he is being persecuted under the widely criticized Section 57 of the country’s Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act. Alam is not its only victim. Amnesty International estimates that more than 100 people have been targeted in a crackdown over the last weeks alone.

Still, his high-profile case has put a spotlight on the alarming degeneration of rights in the country and the region.

The political background surrounding Alam’s detention is intricate, but the injustice is clear-cut. For a primer, Salil Tripathi has done an excellent job placing Alam’s case within the current political moment in Bangladesh for the New York Review of Books. For those just learning of his case, supporters have put together the informative—and stirring—video below, assembling the facts and relevant footage:

By now, many observers have urged his unconditional and immediate release, ranging from National Geographic to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner and, over the weekend, a number of Nobel Peace Prize winners and other well-known personalities. This morning, the theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has an opinion piece about Alam’s case in the New York Times.

On August 15, the FreeShahidul Facebook page reported that several colleagues had visited him in jail. His message for supporters: “Keep up the good fight.”

The attention fixed on the case has been important. Alam’s partner, Rahnuma Ahmed, has written that “the outpouring of national and international protest has prevented further torture”—though she added that a counter-information program is underway to discredit Alam.

I already wrote about Shahidul Alam’s many achievements in a previous article. However, it seemed to me that his significance as a figure still remained too little understood, so I reached out to a variety of his international supporters for words on why they support him.

Given his decades of work, they were not hard to come by. Below, find testimony from a diverse array of artists, photographers, and collaborators who have worked with Shahidul Alam. #FreeShahidul

It was in the early ’90s that I worked as a photojournalist. In those days the only time the international media covered Bangladesh was when there was a flood. It would only make a story if the deaths had been more than 500. The moment the floods started photographers started booking their flights to Dhaka, looking for aerial shots of marooned people and bloated bodies. The rest of the year there was no news of Bangladesh, until the next flood.

Shahidul Alam changed all of that forever. He challenged that view of Bangladesh not just with his work but by setting up Drik Picture Library, and then establishing Pathshala, where he taught photography to all who wanted to learn. He created the only space for photographers in the entire region. As [the Kolkata-based photographer] Ronny Sen said, “He gave us the sky in which we learned to fly.” This was followed by Chobi Mela, the one major festival for photography in the region, where he invited leading international figures to come and give talks and workshops. No one has been able to even come close to such a contribution to the medium to photographers in India.

It was this year that I went to give a talk to students of Pathshala. I was a bit nervous as I don’t have the patience for teaching, but the students were the most focussed group I have ever met. They were soaking up each word, they were hungry—they had learnt how to learn.

It is an outrage that Alam has been detained for telling the truth. We all hope a speedy release will follow.

Given the size of the country, it has more going in photography than almost any other country in Asia, apart from Japan, and this is down to one man: Alam.

I had the privilege of being invited to Dhaka to run a workshop from Alam and knew immediately this was someone who made things happen.

Reza, photographer

“Shahidul Alam” means “Witness of the World.” He has honored his name and beyond, not only as a great photographer but as an educator, a teacher, a human rights believer, and a great speaker, all with a great heart.

I have known Shahidul for over 20 years, from when he started the first “Photojournalism Institute” and invited me to be the first educator. He has helped to train hundreds of photographers, journalists, educators. But, more than that, he has sacrificed his life to Humanity.

He should be given the highest recognition by Bangladesh’s government for all he has done and is doing for his country and the world.

Rally demanding freedom of Shahidul Alam at National Museum, Dhaka.

I met Shahidul Alam in Mexico City many years ago and I have always admired him for his quality as a human being and as a photographer and professor. It is so impressive how his great example has shaped so many students of photography in Bangladesh. He is a man who always looked for peace.

It is unthinkable that this should be happening to him—it is such a great injustice. We in Mexico are all shocked, and we disapprove of the way he has been treated by the police in Bangladesh.

He is one of the photographers that I most admire. Many others in Mexico feel the same. No one else in the world has done comparable work to support the communities of his country.

We hope there is justice in his case.

Shahidul has for years been a leading light among non-Western photographers in what he called the “majority world,” teaching many of us near and far by example, and with his indomitable spirit and dignity. It’s distressing to see this happen to a person who has sought justice for others all his life.

Renowned Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam at a hospital in Dhaka on August 8, 2018. Photo courtesy AFP/Getty Images.

I have know Shahidul Alam professionally from the very beginning of my career for over 20 years. I met with him many times at the World Press Awards held in Amsterdam and he invited me to Bangladesh to give a lecture and a workshop to both Bangladesh and Australian photographers at the Chobi Mela Photo Festival in 2013. Chobi Mela is the first festival of photography in Asia that brings together the best of Bangladesh and international photography and photographers. Shahidul created it. He has nurtured the younger generation of Bangladeshi photographers through the Pathshala South East Asian Institute, which he also created. Many of the photographers have found success, and international platforms to show their work. He also founded the Drik Picture Library and Drik Images, a multimedia organization, photo archive, and stock library.

For me, Shahidul brings the equivalent to Bangladesh photography that David Goldblatt brought to South African photography. The difference being that David was honored and Shahidul is imprisoned.

The new generation is more connected in a world context than ever before, and, as we have seen in the rest of the world, old narratives that don’t work will change. My message to the Bangladesh government is: Why not work together and listen to those that have different views, as their time will come anyway? Free Shahidul Alam and all the other students arrested.

Protest continues in Bangladesh demanding immediate release of photographer Shahidul Alam and all students, August 18, 2018. Image courtesy FreeShahidul Facebook.

Sally Stein, professor emerita, Department of Art History, UC Irvine

I first met Dr. Shahidul Alam at a photography conference in Ireland around 11 years ago with my late husband Allan Sekula. I was instantly struck by his passion and eloquence in terms of his own photography and the work he was doing creating media infrastructures (a school, a photo agency, a photo festival) in his home country of Bangladesh that served as a magnet for much of South Asia and beyond. I also started following his blog, which was consistently thoughtful about social and cultural events in his country, the region, and the world at large. I soon grew utterly impressed with him as committed documentarian and exemplary citizen of the world.

A much-sought-after speaker throughout the world, he was often in transit and thus stayed in my home at least twice when he was in the LA region. On both occasions, I arranged for him to give lectures about his work as a photographer and also as a teacher and media organizer. The most recent was at USC, where students were awed by his presentation and accessibility. The talk he gave nearly a decade ago at CalArts is still mentioned from time to time by some of the students and teachers who attended.

In sum, we all suffer from Alam’s detention and imprisonment, for his is a voice and vision that adds to diverse global conversations about life on the ground and the chronic abuse by those in power.

Our friend Shahidul Alam, a kind and brilliant man who has inspired so many and who has planted seeds for greater visual and civic literacy in Bangladesh, throughout the region, and around the world, was wrongfully arrested for practicing his civic duty to speak in defense of his fellow citizens. The question that occurred to me is: Why do regimes fear artists? And part of the answer, of course, is that they recognize: art is power. His arrest is an affront to the global creative community and a threat to free expression.

Shahidul Alam’s contribution to the discourse around photography in South Asia is inestimable. Most photographers, like most artists, are inevitably concerned with their own practice. To make one’s work takes time, and solitude, as much as community. In recent years, and fairly consistently across India, when I have seen the work of young photographers and asked them where they have learned, several promising talents have named Pathshala as the place.

Growing up in the subcontinent, we had no opportunity to learn photography. Having studied painting and applied art at the Delhi College of Art, I discovered photography only as a subsidiary in my last year. Seeking places where I could study further, all I could find were the short courses at Triveni Kala Sangam. Today we have a few forward-thinking institutions that are opening their doors, but they are still far too few, and not always affordable to all.

Shahidul started Pathshala to encourage young photographers across every class of society, and it is no coincidence therefore that today he is being held for supporting young students. In our hierarchical subcontinent, where age is seen as supreme—for many good reasons, too—it’s inspiring to see men like Shahidul stand with the young.

A great doctor recently said to me, “All doctors are roughly the same, it’s more important to be a good human first.” Shahidul Alam is that good man, for whom photography might be the means, but the true aim has always been to use images to highlight injustice and inequality—through Chobi Mela (perhaps the most respected photography festival on the subcontinent), Drik Picture Library (with its formidable collection of images), Pathshala (which has produced some of the most eminent photographers in Bangladesh), and, not least of all, his own powerful work. And to have shared his knowledge and resources freely so that this endeavor cannot and will never die—we are all eagerly awaiting his release so that he can continue his important work.

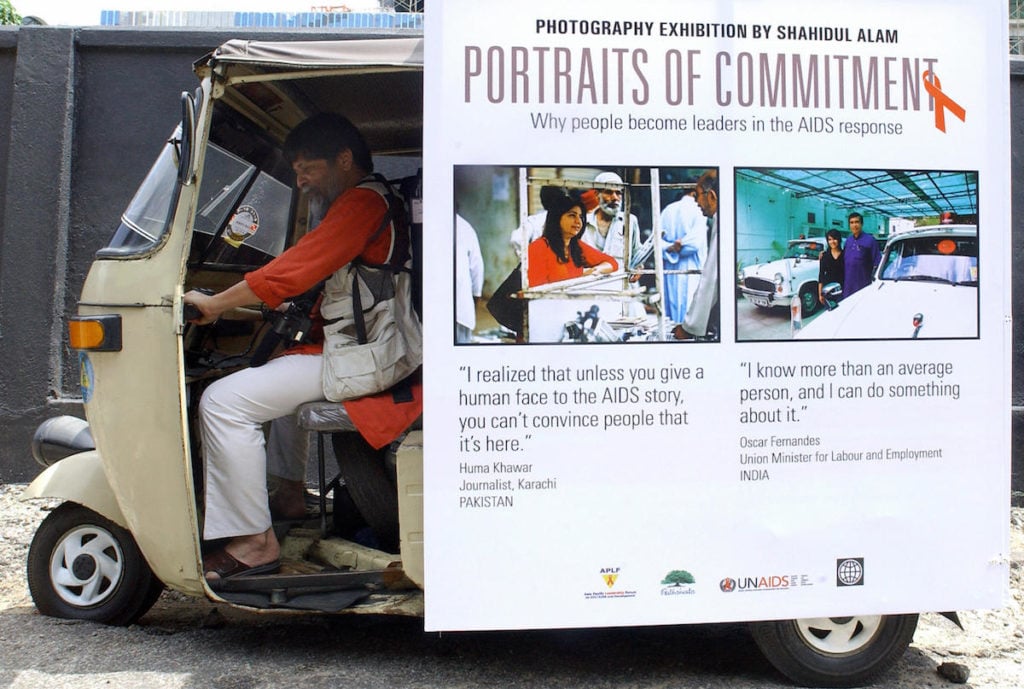

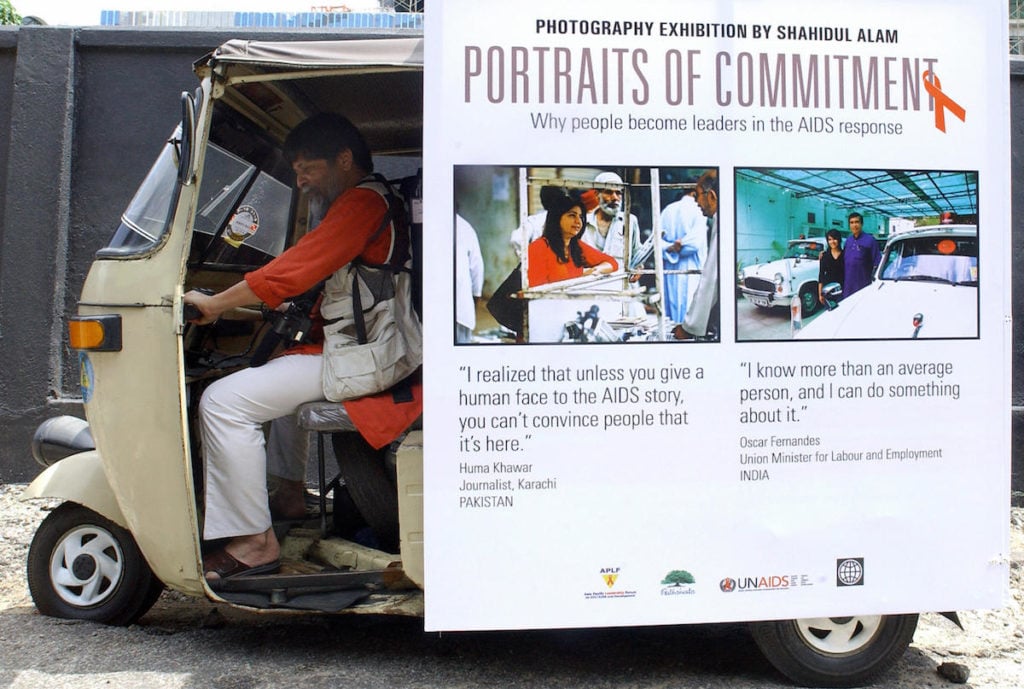

Shahidul Alam drives an auto rickshaw as he launches his mobile exhibition of “Portraits of Commitment” in Colombo on August 19, 2007. Photo courtesy Sanka Vidangama/AFP/Getty Images.

We owe so much to Shahidul Alam. He took on the white, male, colonial nature of our profession—and its gaze—years ago, long before most people had even thought to question it. He didn’t hesitate to take on Western media outlets for their shallow portrayals of what he so brilliantly terms “the majority world” (refusing to accept the more pejorative, Western-centric terms “third world” and “developing world”). And he didn’t just take the media to task—he created a platform for majority world photographers, turning Bangladesh into a place that harbors some of the most creative, productive photographers around the globe today. Shahidul doesn’t wait for permission, or for someone else to give him opportunities. He makes them. And he does that, and has done that, in the face of incredible odds.

Neo Ntsoma and Shahidul Alam. Image courtesy Neo Ntsoma.

Between 2002 and 2003, I was a tutor at Pathshala South Asian Media Academy in Dhaka, Bangladesh, under the leadership of Dr. Shahidul Alam. He was my boss. He later became a friend and now my true brother and uncle all wrapped up in one. What struck me most at the time was how passionately committed he was about mentoring young photographers, a gift he instilled in me and will forever cherish. Meeting him was a turning point in my life and career.

But most importantly, not only is he an incredible teacher and mentor, he is also regarded as “a leading light among non-western photographers in what he calls the ‘majority world.” His reputation worldwide as a spokesperson for the marginalised and disenfranchised cannot be disputed. In 2004, he founded Majority World photo agency with the intention to nurture and promote the work of photographers residing in “the third world” regions by opening new channels for them to tell their own stories, as well as the opportunity to establish their own digital enterprises. Through his global networks he has assisted countless photographers in making their vision a reality, particularly those that remained largely invisible to the global image market—myself included. I was one of the first photographers to be represented by his agency. Still the best decision I’ve made in my career to date. Today I can proudly say that people know of my work in countries that I cannot even read the language and it’s all because of his support.

I am a journalist, photographer, and co-founder of one of the world’s most prestigious photography organizations, FotoFest International. I and my partner, Fred Baldwin, co-founder and chairman of FotoFest, have known Shahidul Alam professionally and personally for 35 years. In the field of photography and international journalism, he is respected throughout the world as an educator, photographer, and emissary for the country and people of Bangladesh. Through his school and photo agency Drik and the media festival he founded in Bangladesh, he has given professional training and jobs to hundreds of young Bangladeshis, providing them with a means to have respected careers and a sustainable livelihood. He is sought after as a featured speaker across the world. I have been at conferences with him from Mexico, Brazil, and London to Abu Dhabi, Beijing, and New York. He is an innovative thinker, a consummate professional, and a widely honored spokesperson for his country, Bangladesh. His arrest and treatment in recent days at the hands of the Bangladeshi government has deeply negative reverberations across the world.

Anne Wilkes Tucker, curator emerita, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Within the history of photography there have been a few—a very few—photographers who maintained their career and simultaneously created pathways for others. In the majority world, those pathways were harder and opportunities close to nonexistent—no professional schools, no agencies to market their work, and no mentors. Shahidul Alum founded the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, which trained hundreds of photographers from all over southern Asia. He also created the Drik Picture Library photo agency and directed Bangladesh’s first photo festival. The festival allowed students to see exhibitions of works by internationally recognized photographers and to meet them. It also provided opportunities for the invited guests to become aware of the depth of work being done in Bangladesh and neighboring countries. Alam created networks. It’s his voice and influence that the country wants to silence because it is a voice of empowerment.

Shahidul Alam last November at our CatchLight Summit in San Francisco. Image courtesy

Christopher Michel.

CatchLight, San Francisco nonprofit promoting photography and social change

Anyone who has had the pleasure of meeting Shahidul Alam knows him as a warm and brilliant soul. We are honored to have him as an advisor to CatchLight. He is a courageous and visionary leader in the arts and has worked for decades to protect human rights in Bangladesh by building spaces for photographers and photojournalists to learn, grow, share, and to reflect their own communities. We join the global outrage at this violation of his freedoms and recognize the vital role that the media plays in holding government accountable, everywhere. He has improved the world for so many, and it is now time for us to help him. We demand his safe and immediate release and remind the global community to stand behind his call for political justice and freedom of speech.

Shahidul Alam is a force that has not only changed the world around him with his images but has created an entire generation of visual storytellers through his photography school. With his unyielding generosity, courage, and foresight, he always sees the purpose and power of the visual medium. His impact on photography in Asia and beyond is immeasurable.

Lars Boering, director, World Press Photo

Shahidul Alam is a legend in world photography, a friend whose decades-long commitment to the arts and journalism has made new perspectives possible. Nobody should be detained for peacefully expressing their views, and Shahidul must be released immediately and unconditionally.

Shahidul Alam is one of the most important cultural personalities in Asia. He is the photographer’s Nelson Mandela. Alam is a wonderful personality, a great photographer, and a freedom fighter. Shahidul Alam is a hero!

I feel sad and outraged that my friend Shahidul has been in still being held in prison in Bangladesh.

I have appreciated his ongoing support for my “Drowning World” project. A few years ago he admonished me, “How could I be doing a global project about flooding and climate change without including Bangladesh?” When I did finally travel to Bangladesh in 2015 to document a flood, he and the team at DRIK were hugely supportive.

For me he is a truly inspiring figure—both a great photographer and a social activist of utmost credibility. He has had a huge impact on photography in Bangladesh, mentoring many emerging photographers and establishing a great teaching institution. He is also such a kind and gentle person.

This portrait was made over Skype during a recent call with him:

Portrait of Shahidul Alam. Photo courtesy Gideon Mendel.