Opinion

State of the Culture, III: How ‘Contagious’ Media Killed Art Criticism

The internet has radically changed the way we write about art—and what kind of art gets covered at all.

The internet has radically changed the way we write about art—and what kind of art gets covered at all.

Ben Davis

In parts one and two of this series, I looked at how a changing media environment was putting pressure on art institutions and artists, respectively, altering their relationship with the public at the same time. For my final installment, I’ve gathered my thoughts on my own little piece of this puzzle: the sphere of writing about art, and the evolving role of art criticism.

These days, Jonah Peretti has achieved web-media guru status, having been a prime mover behind both HuffPost and Buzzfeed. There is a story to be told, however, about how this new wave of media was incubated within art, sprung from the side of “culture jamming” or “tactical media”—terms for lefty media-hacking stunts of the kind pioneered by the Yes Men.

Jonah Peretti of Buzzfeed speaks onstage at the TechCrunch Disrupt NY 2013. Photo by Brian Ach/Getty Images for TechCrunch.

In the ’90s, he had styled himself as a postmodern critic of the emergent commercialization of the web, looking to Marxist-psychoanalytic philosophy, queer theory, and appropriation art as strategies to “challenge capitalism and develop alternative collective identities.” Then in 2001, at grad school at MIT and riding the energy of the anti-globalization movement, Peretti got his first taste of the limelight after attempting to subvert Nike’s sneaker customization service, requesting a shoe emblazoned with the word “SWEATSHOP.”

Nike declined. Peretti sent his email exchange with the shoe giant to a few friends; it spread quickly and became a sensation.

He wrote about/theorized the experience in an essay in the Nation called “My Nike Media Adventure,” lauding the emerging activist power of what he called “micromedia” to reshape the public sphere.

“My guess is that in the long run this episode will have a larger impact on how people think about media than how they think about Nike and sweatshop labor,” he concluded. The experience of the political power of email forwards led Peretti to coin his own term: “contagious media.”

The term caught on. Shortly after the Nike incident, Peretti joined the then-Chelsea-based art-and-technology incubator Eyebeam, where he would found the Contagious Media Lab. In 2005, he and his sister, comedian Chelsea Peretti, scored a show at the New Museum, also called “Contagious Media.”

Installation view of “Contagious Media” at the New Museum, 2005. Image courtesy the New Museum.

The show celebrated the viral artifacts of the day, like the Dancing Baby, “All your base are belong to us,” and Hot or Not (a site which, incidentally, inspired the creation of both YouTube and Facebook). It also included squirm-inducing projects from the Perettis about white people’s tone-deafness about race (Black People Love Us!, 2002) and sexual harassment (The Rejection Line, 2002).

Curator Rachel Greene—who went on to literally write the book on net art—touted their work as heir to 1970s media activism, with a “strong relation to the identity-based and political artwork of the 1980s such as the works of American conceptual artist Adrian Piper.”

The show was not well reviewed. Still, a conference accompanying the “Contagious Media” show attracted artists and designers and creative directors, all trying, as NPR explained at the time, to crack “the science of goofy stuff on the Web.” Jonah Peretti also took the occasion to organize the Contagious Media Showdown, placing web-art projects in head-to-head competition with each other to see which could spread fastest.

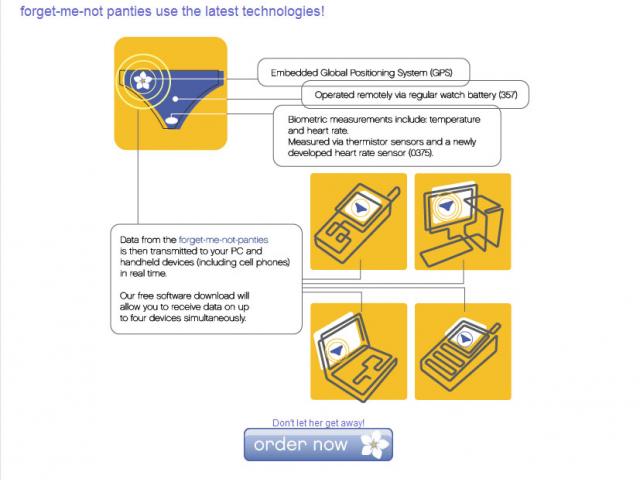

The satirically bro-ish winning entry was a line of GPS-enabled women’s underwear that you could connect to your computer (“including cell phones!”): the Forget Me Not Panties. Its website racked up 615,562 unique visitors during the Showdown. (By contrast, it would be a big deal for the New Museum when, seven years later, its Carsten Höller showcase cracked 100,000 visitors.)

Screenshot of the Forget Me Not Panties website.

Two days after the Contagious Media Showdown ended, Peretti helped launch the Huffington Post: a model powered by celebrity and liberal sentiment, high volume and low-to-no pay.

One year after that, Peretti would found Buzzfeed. Initially, it was a project with no writers at all, just an algorithm that measured how “contagious” things were around the web.

As any reading person knows, in the decade-plus since, journalism in general has been reshaped, first by the rise of online media, then by the takeover of public conversation by social media. For the most part, the forces stretching art coverage are simply local permutations of these larger forces.

Mary Louise Schumacher, Ossian Ward, and Sarah Douglas on the panel “The Privatization of Art Journalism” at Art Basel in Miami Beach 2017. Image courtesy Art Basel.

As ARTnews editor Sarah Douglas said candidly on a recent panel:

The traditional art magazines, the ones that rely on the advertising model, are struggling—I say this with caution because in some ways art news is thriving like never before—and art coverage in newspapers around the country is shrinking, or, just as importantly, changing. Becoming shorter, punchier, social media friendlier.

The causes are familiar to anyone who follows the endless tide of bad news about the media industry. As attention migrates online, the web’s accelerated velocity puts stress on the old default values of print.

On the internet you can track what your readers actually respond to in real time. The Big Board overlooking Gawker’s offices and showing traffic was a minor media scandal back in 2010. Now every online newsroom, artnet News included, has something like it glowering over all of their work: a screen quantifying what is hot, and what is not, at any moment.

Such tools also tell you, among other things, how readers are finding you (social, search, email newsletter, link from another site, etc.), making plain the degree to which a publication has lost the ability to control an audience’s attention. A stunningly small percentage of any website’s readership comes through its homepage.

Promotional image showing Chartbeat in use in an office. Image courtesy Chartbeat.

Facebook, Google, and other aggregators own the attention of the audience—they have become the real homepage. And every new article competes individually in these streams against every other possible kind of thing that might fascinate or inflame an audience, from the President’s latest toxic Tweet to GPS-enabled underpants to your cousin’s new baby pictures.

(According to Facebook’s recent tweaks to its algorithm, stories would likely be prioritized in this order: baby pictures, toxic Tweet, underpants, art news story.)

The old idea of a publication as a balanced whole breaks down, replaced by the idea of “content” as an unending stream of disconnected items, all in competition to justify the time and effort put into them.

For culture, such an environment creates a newly flattened sense of value. “If you want to look at the entries as art or entertainment or social commentary, it is possible to think a project is great, even if it is not popular,” Peretti told the now-defunct local-news site Gothamist during the Contagious Media Showdown. “But for the showdown the ultimate yardstick is traffic.”

In effect, every day is a Contagious Media Showdown now.

All of this is just a way to put into context a very common, much lamented feature of the contemporary art-media landscape: the waning of “serious criticism.”

Heck, I’ve written about this before. Seven years ago, in an essay called “Total Eclipse of the Art” I wrote:

Readers care a lot more about reporting on the art world than they do about reviews of art. By whatever metric you use—Web traffic, reader feedback, or just percentage of the collective brain taken up—people are more inflamed by the latest institutional scandal or art-related celebrity sighting than they are by quaint, old-fashioned discussions of what, exactly, makes an artwork good… As in a solar eclipse, the halo around art grows ever brighter and more distinct, even as the light source itself vanishes from view.

This was actually before the real takeover of “metrics” intensified scrutiny and atomization; before Chartbeat entered my world; before social-media analytics; etc.

Ruthless quantification is not going to be kind on things as finicky and subjective as aesthetic judgement in general (see the New Yorker‘s Alex Ross last year on “The Fate of the Critic in the Clickbait Age“). The culture pages are thinning out fast at media outlets everywhere.

But the new landscape is going to be particularly unkind on judgement of experiences that are smaller-scale and more local. Because no part of the media is being more ruthlessly pulverized by the new media logic than local news.

This is an important point: As an institution, the ordinary art review—the kind of writing with the implicit understood justification of answering the question, “Is X experience good enough that I should go see it in person?”, what Orit Gat calls “service criticism”—is by the nature of its object a sub-genre of local coverage.

Viewed that way, there is an implied upper limit on how many interested readers you can get: the number of people who might actually go to see a gallery or museum show. The numbers say pretty definitively that the amount of people who seek out review coverage of art shows they can’t personally go to or aren’t personally connected to is small.

You have seen online art coverage deflect towards news and opinion at least in part because these have a range that carries beyond this local “service” context.

The realities of scale needed to compete online are so relentless that giant media brands like the Times and the Guardian have decided that actual national-scale markets aren’t big enough for them. They have decided that their audience needs to be everywhere. Indeed, the Times has set its sights on being the “indispensable leader in global news and opinion.”

Global thought leaders: Thomas L Friedman, Brandon Busteed, David Coleman, and Stefanie Sanford at The New York Times Next New World Conference. Photo by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images for New York Times.

When, on the other hand, the Times terminated its tri-state art coverage, it reasoned that “the resources and energy currently devoted to these local pages could be better directed elsewhere.”

Simultaneously, “service criticism” is hit from both sides, because the change of its readership’s habits is matched by a change in the status of its object.

Capitalism by definition is based on the constant drive to expand profits. And so capitalism applied to culture must grow its share of your attention constantly, which means crowding into new spaces, creating new audiences, shortening the distance between cultural production and consumption.

Crowding into new spaces: Visitors at the Musee des Tissus (Museum of Textiles) in Lyon. Photo courtesy Jeff Pachoud/AFP/Getty Images.

The young Marxist theorist Jonah Peretti wrote about this acceleration of internet culture as a terrain of struggle for radicals: “In a fragmented cultural milieu, capitalist, consumer culture can thrive unopposed.” The slightly older Contagious Media champion Jonah Peretti saw the genre as powerful exactly because it opened up a vast new front of networked cultural consumption:

The Internet is powered by bored office workers who sit at their desks forwarding emails, surfing the web, reading and writing blogs, and IMing funny links to their friends. These people have inadvertently created the Bored at Work Network (BWN). It is amazing to me that the BWN can distribute media to literally millions of people each day without any centralized coordination. The BWN is bigger than CNN, bigger than Fox, bigger than NBC, CBS, or ABC and it is powered primarily by people goofing off at work.

Since that pronouncement, the rise of the mobile web probably changes the calculation a little—but it mainly adds the Bored at School, the Bored in Line, and Bored on the Toilet networks to the mix. The front of media is everywhere and constant.

The point of tracking down the arty connections of “goofy stuff on the web” is to show that in a way it is dangerously more comparable to certain functions that art claims for itself than you might think. Not totally—but enough to crowd it.

And “contagious culture” is optimized for efficiency of consumption. A reader being offered a review of a piece of art that they can go see elsewhere is being asked to take at least one more step than someone reading something that they can experience as it is meant to be, right there, in-browser.

Maybe all this sounds hyperbolic. But the research shows that all “location-based entertainment”—experiences that you have to go to, instead of them coming to you—is becoming something a general public consumes more rarely. The NEA says consumption of most kinds of culture is falling, except for digital consumption, which is surging. The Times is running opinion pieces with titles like “Is Staying In the New Going Out?”

That is another headwind for art writing, in its consumer service mode at least.

These are not especially happy thoughts, but we ought to look the situation in the face to decide how to crack the puzzle and proceed.

The analytics tell me that this article is way over its optimum length, though, so I will finish up with a part IV tomorrow.