Opinion

State of the Culture, IV: Why the ‘Art World’ as We Know It Is Ending

There's breakdown of institutional roles underway.

There's breakdown of institutional roles underway.

Ben Davis

In Part I of this series on the State of the Culture, I looked at the changing environment for museums; Part II was dedicated to the changing rules for artists; Part III examined the new dynamics of art media. In Part IV, I try to sum things up.

***

Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas is a kind of parody of 19th-century cocktail-party clichés. There’s an entry for “Photography.”

It reads: “Will replace painting.”

“Technology is changing everything!” has been a cliché for as long as there has been technological change. On the other hand, cliché and parody are both different ways that society brings fearsome change down to manageable mental scale.

Photography didn’t replace painting. But it did, after all, dramatically transform what people valued in it. Almost everything we know or think about modern art comes from that fact.

There was an awful lot of routine and dutiful European painting, whose main justification was to offer evidence of things seen. That went by the wayside—and you got dramatic and adventurous new kinds of art in its place, as artists were freed up from their habitual justifications for making what they did.

Who can predict where it is all going? It does seem, however, that an awful lot of the routine and dutiful functions of art (and writing about art) are probably in the process of being reformatted by the last decade’s worth of technological changes, if not superceded.

Left: Francois Boucher, Portrait de Marie-Emelie Baudoin (1760); Right: Recreation of Boucher’s painting by Audrey Pirault (@audrey.pirault) for Paris Musées’s 2016 campaign using Instagram influencers to recreate paintings.

People are always talking about the intensifying love affair of fashion and art. Well, in the fashion world, there’s a cold war between social media “influencers” and fashion critics for relevance.

If the main point of culture writing is just what Renata Adler once disparagingly called the “consumer service” function—“this is okay, this is not okay, this is vile, this resembles that, this is good indeed, this is unspeakable,” all the stuff that boils down to ‘Should I buy? Should I go?’—then getting attractive people to show up and show off for their many followers may actually be preferable, from an institutional point of view, than critical appraisal. Influencers, as Fashionista wrote, “move product.”

(I just received an invite to a “special press/influencer preview” for an exhibition at the New York Public Library—the first time I had seen those two terms grouped together in exactly that way in an art context. The subject is ’60s counterculture. The hashtag is #WantARevolution.)

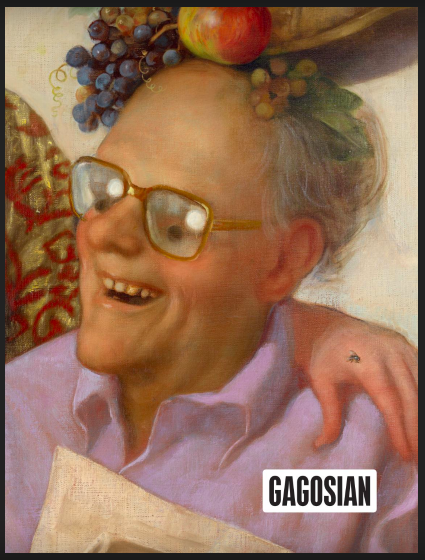

The cover of the fall 2017 issue of Gagosian Quarterly.

Nevertheless, I could also point to many examples of fine-art publications trying to cut new paths through the jungle. In just this last year or so, the following initiatives entered the picture:

I’m sure I’m missing some other good ones.

Still, even this very proliferation of experiments from new points of origin suggests that the underlying assumptions around art are shifting. It shows how the discourse is up for grabs, and how different functions—publisher, artist, dealer, museum—are collapsing together into new mixtures.

Why focus on the challenges then? Of course, tons of people are obsessed with social media already—if there’s one thing social media does it is monopolize the conversation. I just think the topic deserves to be treated as more than as it is now, which is as a cosmetic question: audience development for museums, career development for artists, media strategy for publications.

It is more deeply unsettling than that for art.

In 1972, Lawrence Alloway wrote a dense but important article for Artforum, “Network: The Art World Described as a System.” In it, he surveyed the changes to the values of art that had come in the decade before (i.e. the ‘60s) when, in fact, the term “art world” had come into currency (usually dated to Arthur Danto’s essay “The Artworld,” of 1964).

To my mind, Alloway’s most clarifying point is this:

What is the output of the art world viewed as a system? It is not art because that exists prior to distribution and without the technology of information. The output is the distribution of art, both literally and in mediated form as text and reproduction.

It is not the creation of art that defines our sense of an “art world,” as Alloway viewed things. Plenty of art-making is done in places where there is no art scene, let alone art world.

The conversation around and among the art, the system that places it into self-conscious relationship with itself and with the rest of the society, is decisive; it is the world.

The artist as celebrity in the 1960s: TV host Ed Sullivan (left) with Salvador Dali, who is showing how to paint with a spray gun. Photo courtesy AFP/GettyImages.

Alloway saw his moment as one of plate tectonic shifts. Old-fashioned ideas of artists as solo outsider geniuses were rubbing up against a new sense of visibility and importance provided by increasingly assertive institutions for circulating art: the museums, which were now actively shaping contemporary art rather than presenting established historical treasures, and the media, which was increasingly shining a spotlight on artists as celebrities and art as a lifestyle.

Alloway thought artists and critics were holding onto a kind of split consciousness. They had the righteousness of feeling that art was pure and special and above-it-all but also the sense of self-importance and visibility of having their images (or writing) reflected in mainstream institutions and powerful media.

You can say that the sense of a space called the “art world,” as we think about it, was formed by the bubble of energy created by these two currents meeting.

For his part, though, Alloway thought we should junk the pretensions of purity and enjoy surfing what he called the “fine art-pop art continuum.” He considered this ecumenical mindset more egalitarian, mixing high and low culture into fun new combinations without the “dogmatic avowals of singular meaning and absolute standards” of traditional elite culture.

Looking back on our last 10 years as Alloway looked back on his, what you see is an accelerating breakdown of the authority of traditional “institutions of circulation.”

If an “art world,” in Alloway’s formulation, is dependent on the context of art institutions and the media for its sense of self, now those establishments are dependent for their sense of self on the mobile internet and social media.

Museums and galleries compete for one attention space with every other kind of entertainment experience; artists compete with every other kind of social media persona for creative micro-celebrity; and media cannot, without some heroic effort, justify attention on the local dimension of experience unless it somehow plugs into the national (or, better yet, global) conversation as a “trending topic.”

And yet even as its fundamental assumptions about the world are modified, Alloway’s “Network” text looks very prescient—right down to its prophetically cybernetic name.

Chinese tourists pose for pictures at Art in Paradise, an illusion art museum popular amongst tourists, on February 26, 2015 in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Photo by Taylor Weidman/Getty Images.

In fact, at moments he sounds like a regular “post-internet” thinker, several decades before artist Marisa Olson coined the term for a contemporary mindset half-in, half-out of media space at all times and indifferent to the distinction. Here’s Alloway:

It is presumed that aura is lessened when art is reproduced mechanically. Some properties show up more than others in reproduction it is true: autographic solidity is lightened and connections with other artists and the rest of the world are facilitated, but these are nondestructive emphases. It is not possible to restrict the meaning of a work to its literal presence; art consists of ideas as well as objects.

What could better represent the promiscuous aspirations of Alloway’s “fine art-pop art continuum” than a unified, omnipresent space that collapses levels of culture into a single feed? That blurring has effects on meaning: “Now that art is seen in wildly differing contexts, the diversity of response to art is public too.”

In effect, Alloway was prefiguring the idea of “context collapse,” the term social media theorists use to describe how the rapid circulation of images and text eliminate local controlling contextual assumptions; the effect that can lead to explosive, sudden bursts of meme-ified popularity or unwanted scandal.

As Helen Lewis explains the idea: “no matter what your intended audience is, your actual audience is everyone.”

Few contemporary art lovers would disagree with the idea that “art consists of ideas as well as objects.” The notion that context is meaningful—that it even, in many ways, is the meaning—is one of the most fundamental lessons of post-‘60s contemporary art. But what happens when art can no longer control the context of its own reception at all?

One of the most minor things that happens is that our terminology feels dated. Art that becomes more permeable and porous and submitted to asymmetric laws of attention ceases to be able to define a “world” for itself.

You go from a domain you can think of as the Art World to something you should probably define as something else entirely, something that sounds more extensive but also less solid and specific in its connotations: something like the Culture Network.