Art Criticism

The Prospect 5 Triennial Reflects Contemporary Culture’s Hunger for Widespread Yet Specific Historical Reckoning

The fifth edition of the important art survey is in its final week.

The fifth edition of the important art survey is in its final week.

Ben Davis

There’s a great moment at the Prospect 5 triennial, “Yesterday We Said Tomorrow,” at the Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University in New Orleans, where five artists face off in dialogue across four galleries.

A room full of Mimi Lauter’s atmospheric abstractions speak to Naudline Pierre’s colorful fable-on-canvas of winged women. The dream-like atmosphere and buoyant fantasy of Pierre’s work in turn plays as a knowing contrast with Ron Bechet’s large charcoal drawings of rugged swamp floor, which ground you back in the grit of nature. You can feel the deliberate interchange of energies.

Centering the Newcomb presentation are multiple works by the great Barbara Chase-Riboud, a revered artist in her eighties with an unmistakable vocabulary of massed forms and drapery. Alongside several sculptures, Chase-Riboud’s intricate drawings punctuate the walls of a main gallery, their hieroglyphic qualities accentuating the gallery’s other showstopper: Elliot Hundley’s densely coded, mural-sized pinboard epic, The Balcony.

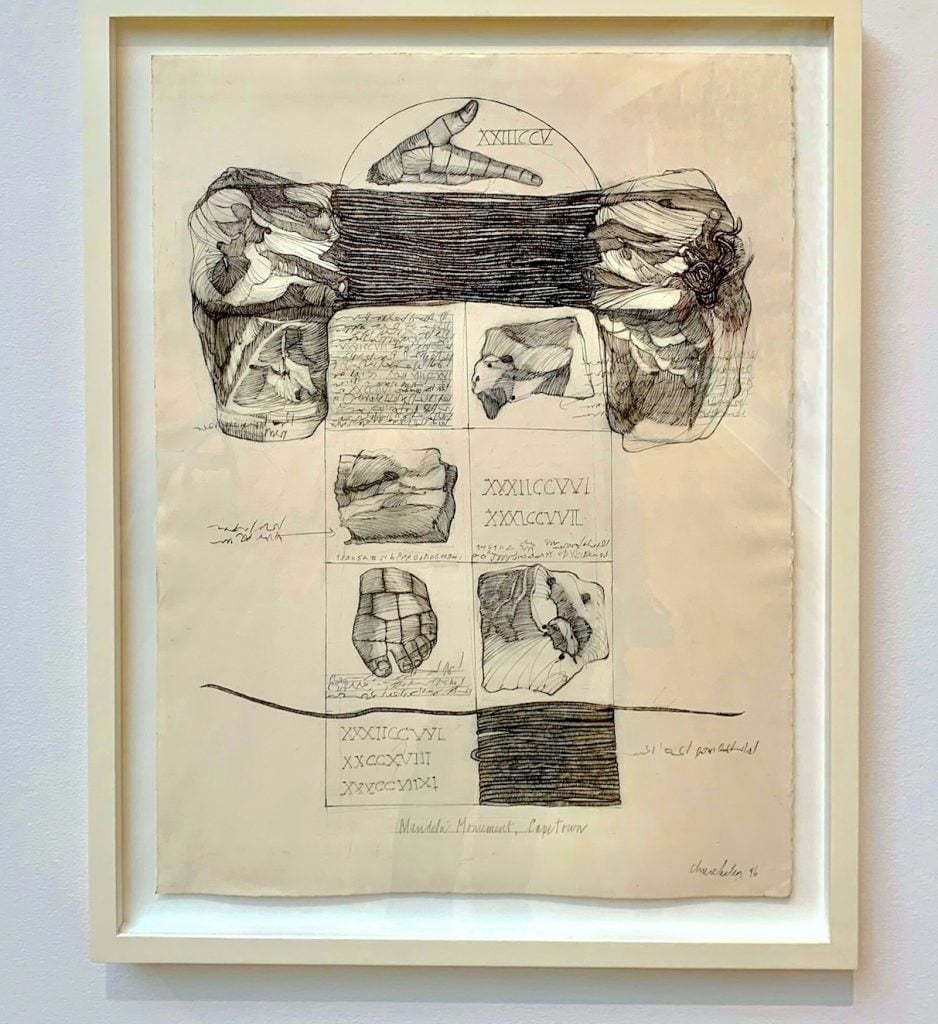

Chase-Riboud and Hundley play off of each other in more than formal terms. Among the former’s drawings are ideas for monuments, such as a Mandela Monument and a tribute to Malcolm X.

Barbara Chase-Riboud, Mandela Monument, Capetown (1996). Photo by Ben Davis.

Hundley’s 40-foot painting, meanwhile, is named after a Jean Genet play; the “balcony” in question is a brothel in a city undergoing an unnamed, unexplained, and possibly imagined revolution, as the clients take refuge there to live out baroque, eccentric fantasies. The flow of images that form the texture of Hundley’s piece captures the sense of the drama of momentous unfolding history but also the confusion of fantasy and reality.

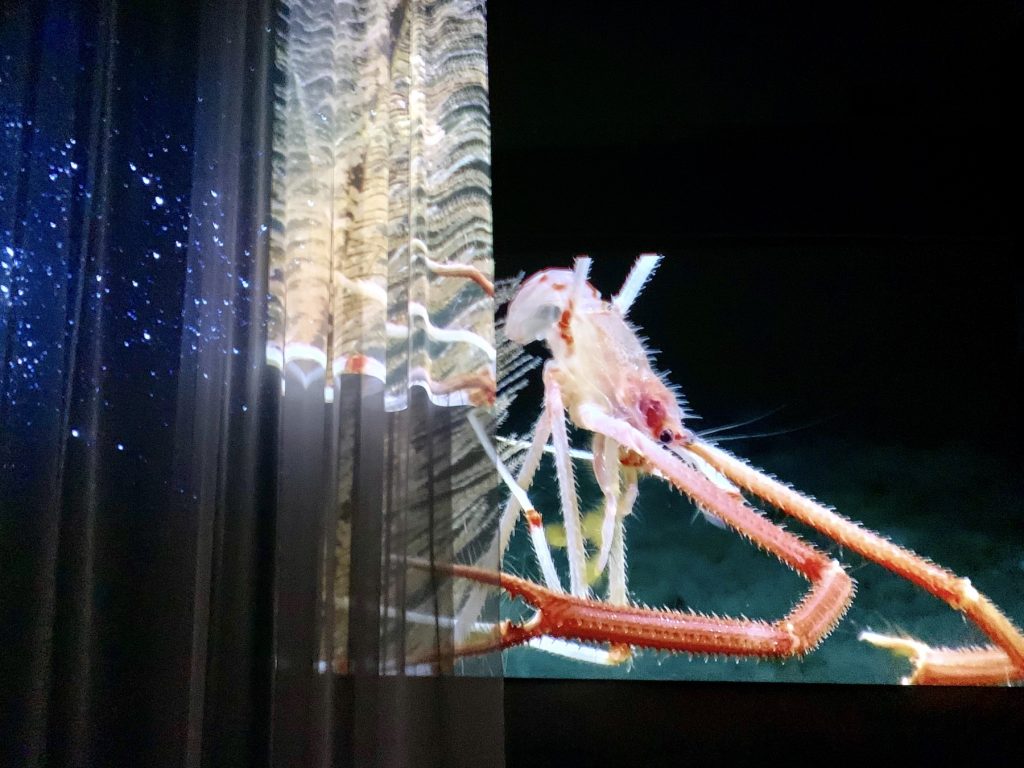

Detail of Elliott Hundley, The Balcony (2020-21). Photo by Ben Davis.

The major themes of this show are all there in this juxtaposition at the Newcomb: honoring the marginalized, questioning how history is received. The way their contrast makes them greater than the sum of their parts is a tribute to curators Naima J. Keith and Diana Nawi.

“Yesterday We Said Tomorrow” still has the challenge of previous versions of this event of feeling somewhat centerless; Prospect New Orleans wants to be a city-wide event, but in practice this means that big parts are diffused among a lot of smaller spaces that struggle not to come off as feeling like asides. (I should say that I didn’t see all the parts: when I visited in November, not all of the show was open, as various satellites were still coming online. The organizers chose a “staged opening,” after Hurricane Ida smashed the city and wreaked havoc on their plans.)

Works by Cosmo Whyte. Photo by Ben Davis.

However, there are plenty of discoveries and highlights in Keith and Nawi’s Prospect 5. At the Contemporary Art Center—the central hub of the show, and the only large space wholly given over to it—there are stylishly severe charcoal images by Jamaican artist Cosmo Whyte appropriating historic photographs, and an affecting film essay by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz about the routines of survival in Puerto Rico after its own recent hurricane disasters.

Film by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz. Photo by Ben Davis.

Kevin Beasley, normally known as a sculptor and installation artist, has produced a suite of detailed drawings of a property he has purchased in the city’s Ninth Ward. Their snapshot detail is striking. So is Sky Hopinka’s hushed video diptych following the history of indigenous presence along the Mississippi river. A display of multiple works by the late Carlos Villa includes a robe-like patterned vestment studded with feathers, meant to represent the mixing of influences in his Filipino heritage.

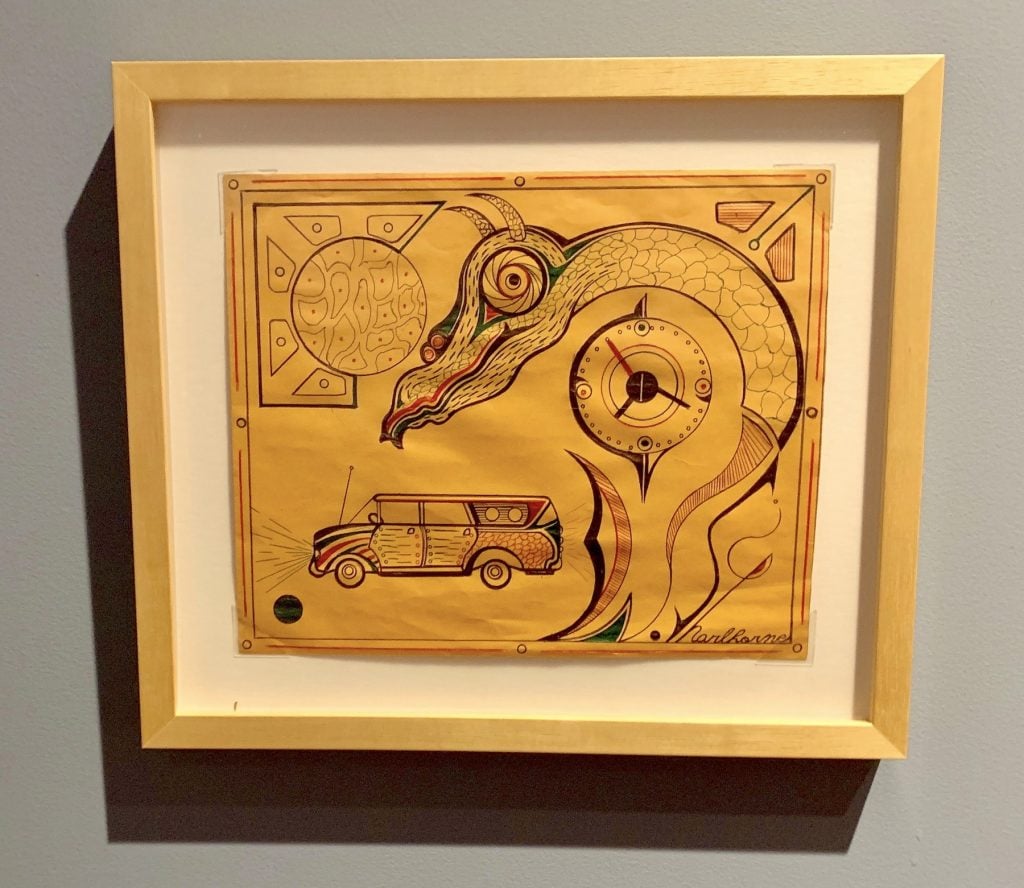

At the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, there’s a gallery given over to a selection of drawings of imagined architectures and beasts by Welmon Sharlhorne. Sharlhorne, self-taught while incarcerated at Angola prison, places a clock somewhere in each drawing—a personal symbol, it seems, of art-making as a way to fill time. The work is fantastic.

Welmon Sharlhorne, All the pretty people of life (n.d.). Photo by Ben Davis.

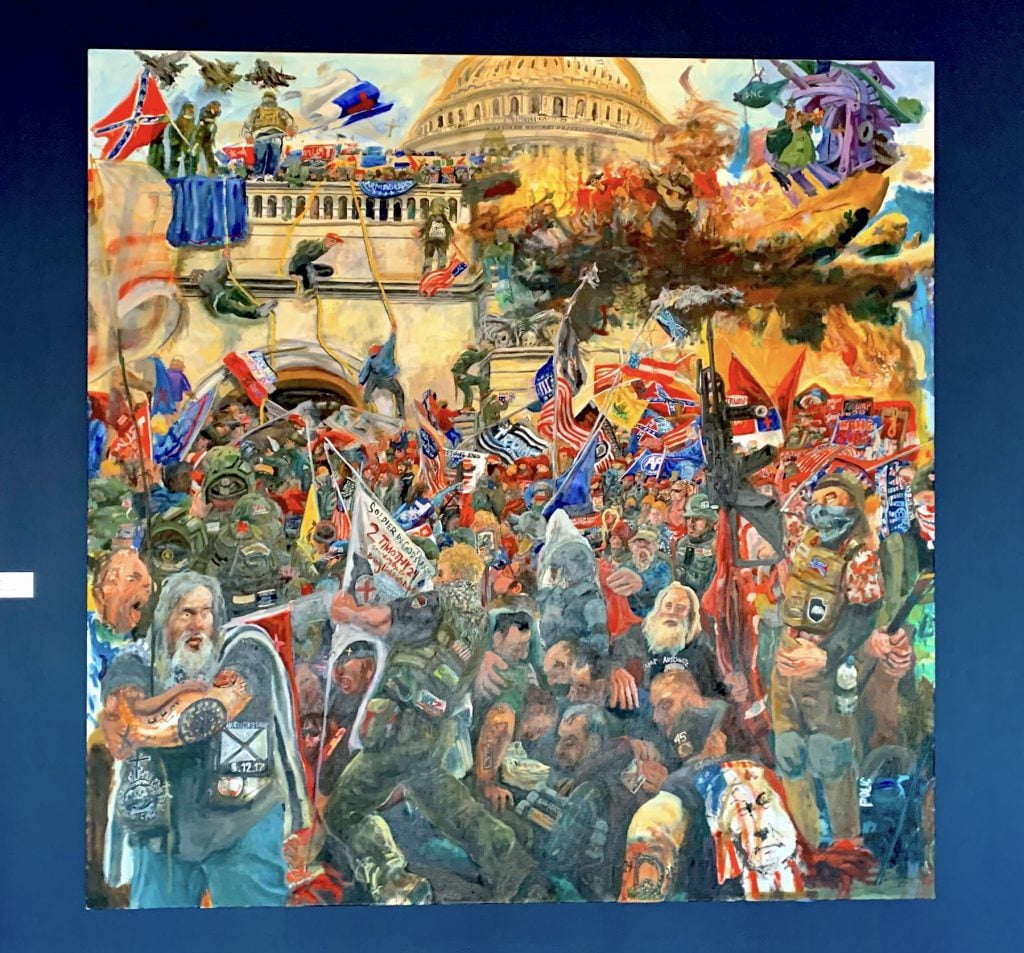

Katrina Andry’s woodcuts, also given their own gallery, reflect on the history of colorism with lucid symbolic economy. And Celeste Dupuy-Spencer’s cycle of large canvasses are one of the more effective examples of contemporary history painting that I have seen lately, compressing the darkness of American history into eddying, symbolically charged scenes.

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Don’t You See That I Am Burning (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

Most importantly, the Ogden also turns over a large section of its Prospect display to the Neighborhood Story Project, a local history initiative, which offers up a series of artifacts, altars, and dense information displays about female spiritual leaders in New Orleans and their practices.

In fact, this show-within-a-show is so dense that it comes to seem the symbolic center of gravity of the entire biennial and its curatorial sensibility: reverent and didactic, but also community-directed and infused with a rhetoric of care.

Display from “Called to Spirit: Women and Healing Arts in New Orleans,” curated by Rachel Breunlin and Bruce Sunpie Barnes as part of Prospect New Orleans. Photo by Ben Davis

Some 80 percent of the artists in “Yesterday We Said Tomorrow” are Black, and the most persistent theme of the art in the show is the memorialization of Black history. At the Historic New Orleans collection, Dawoud Bey offers a video triptych that drifts across the remains of the most completely preserved slave plantation, trembling with portentous music.

Video by Dawoud Bey at the Historic New Orleans Collection. Photo by Ben Davis.

For a mobile project parked at the University of New Orleans gallery, Nari Ward creates an audio collage, to be played from a mobile speaker system. Against a background of droning and Morse code, it features swirling fragments of speeches on the theme of racial justice, so that James Baldwin’s voice alternates with the voice of Amanda Gorman, the young Harvard-educated poet made famous when she spoke at Joe Biden’s inauguration.

Battleground Beacon by Nari Ward. Photo by Ben Davis.

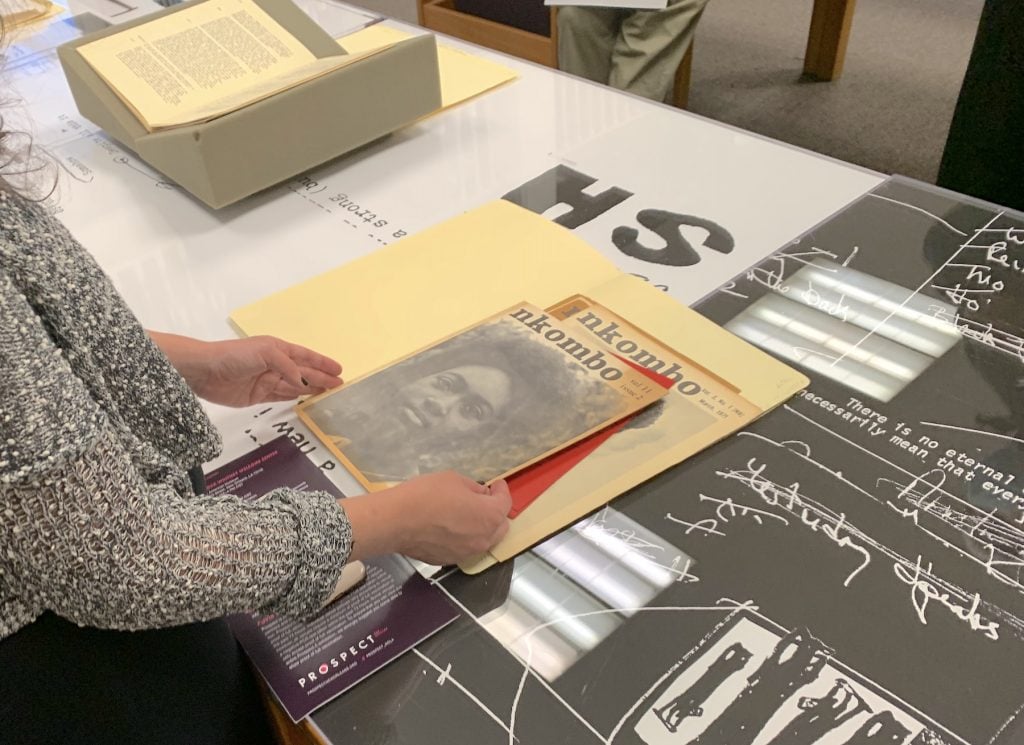

For a Prospect project at the Amistad Research Center, a Black cultural research institute located at Tulane, Kameelah Janan Rasheed encourages visitors to look over copies of Nkombo, a Black literary magazine from the 1970s.

A visitor view Kameelah Janan Rasheed looks at the final issue of Nkombo. Photo by Ben Davis.

Also tapping this energy is the other clear highlight of “Yesterday We Said Tomorrow” for me: the conjoined display, in an abandoned library annex of the Ogden Museum, of works by Glenn Ligon and Jennie C. Jones.

Around the edge of the space, Ligon has studded a series of his signature black-painted neons. Each one memorializes a date when a monument to the Confederacy was taken down in New Orleans, a cluster in 2017 and a cluster in 2020. The chapel-like architecture and the neons’ placement on the ceiling panels above the central annex make them read like beats in an unfolding devotional narrative. You are supposed to get a sense, looking at the dates, that history has happened. But Ligon’s conceptual austerity also feels deliberately removed from celebration.

Project by Glenn Ligon. Photo by Ben Davis.

The accompanying work of Jones, a multifaceted and accomplished experimental artist who’s been getting long-deserved attention, alternates two sound compositions in the chapel-like space, one a blending of multiple gospel choirs singing “A City Called Heaven,” a majestic Civil Rights anthem associated with activist Mahalia Jackson; the other a Jones composition incorporating droning sounds of energetic healing practices, distended bells, and samples of Black composer Alvin Singleton’s experimental music, building in layers and never quite resolving, in a beautiful way.

Taken all together, the Ogden’s architecture, Ligon’s date markers, and Jones’s music create an effect akin to visiting a contemporary shrine, a gathering point for introspection on history and the present.

“Yesterday We Said Tomorrow” feels very much of a piece with the moment that has made the New York Times’s “1619 Project” a contemporary sensation among liberal audiences. Back in 2007, when it was founded, the stated goal of Prospect New Orleans was to contribute to economic revitalization in the tourism-dependent city following Hurricane Katrina: “Since people in the art world tend to be flush, when they show up, they like to live it up,” Cameron explained at the time. Arriving after the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, the stated goal of Prospect 5 is “to examine our nation’s violent history and its current injustices through art,” Keith writes in the catalogue.

I wonder how much these two goals have merged, as meditating on privilege becomes a dominant form of elevated cultural consumption for the “flush” cultural tourism audience. And I wonder what that merger means, and how it shapes how I might think about the pressures on this show.

At the Happyland Theater site, a video by Rodney McMillian plays, Preacher Man II. A preacher character, in a black cowboy hat, re-performs a speech by Stokely Carmichael, civil rights activist and coiner of the term “Black Power.” In a triennial whose overall themes are sacral, here is the fire and brimstone: The speech—I believe the text is Carmichael’s “The Pitfalls of Liberalism”—denounces white liberals for condemning the oppressed Black masses for violent resistance while failing to accept the violence of the white power structure and capitalist economic order.

Rodney McMillian at the Happyland Theater. Photo by Ben Davis.

The Prospect 5 pamphlet advises that “the ideas feel painfully relevant to our moment.” Yet there is something distanced about the video. The staging is so low-fi and static as to be almost anti-aesthetic. The central figure is framed at a distance against a sunny, unspectacular wooded background. It’s paired with another video featuring a rickety staged reading of Barry Goldwater’s The Conscience of a Conservative by a man in a rubber Ronald Reagan mask, amplifying the sense of burlesque.

Maybe there’s a sense somewhere in there that the project of reanimating radical history is both worthy and fraught—a sense of being stuck somewhere between the Mandela Monument and The Balcony.

“Prospect 5 New Orleans: Yesterday We Said Tomorrow” is on view at venues throughout New Orleans, through January 24, 2022.