Op-Ed

The UK Government Has Refused to Compensate Dealers Affected by Its Ivory-Trading Ban. Here’s Why That Has Big Implications

The country's handling of the ban could have widespread legal ramifications concerning personal property.

The country's handling of the ban could have widespread legal ramifications concerning personal property.

Tom Snelling

Ivory dealers and collectors in the UK lost out in May after three Court of Appeal judges dismissed efforts to appeal the country’s strict new ban on the trade of ivory.

On June 12, a company called Friends of Antique Cultural Treasures Ltd, founded to represent the interests of the trade, applied for permission from the UK Supreme Court to take its case against the ivory-trade ban to the top of the judicial chain.

The company argued, unsuccessfully, that the UK’s “world-leading” Ivory Act of 2018, which introduces a total ban (with narrow exemptions) on dealing in items containing elephant ivory within the UK, as well as a ban on exports and imports of such items, was contrary to EU law because the ban interfered with the free movement of goods and antique dealers’ rights.

This case shows that UK courts are likely to expand the situations in which private parties are deprived of the use of their property by the state, even if there are serious doubts about the evidence to justify the interference.

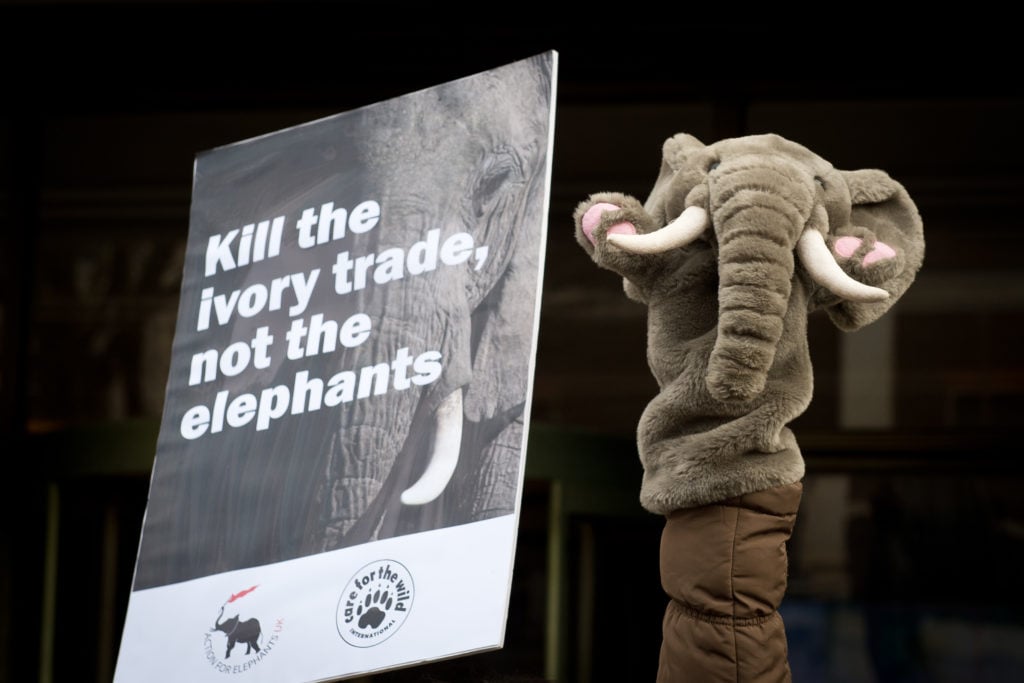

Ivory trade protesters in London in 2014. Photo by Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images.

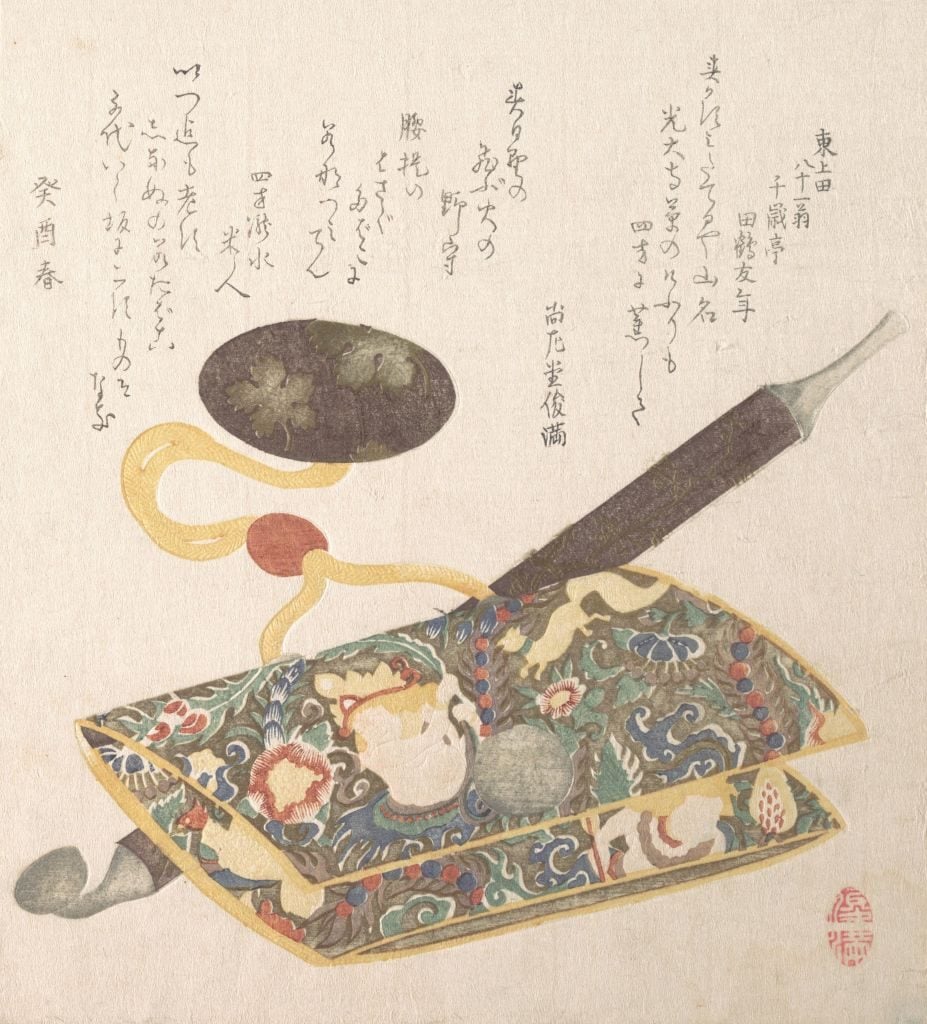

There is no doubt about the importance of attempts to protect African and Asian elephants in the face of harrowing and ongoing threats to their survival. The question, instead, is the effectiveness of banning, with limited exceptions, the sale of antique worked ivory, including netsuke (small carved ornaments, often attached to the sash of a kimono, and crafted in Imperial Japan between the 17th and the early 20th century).

This debate played out before Mr Justice Jay at trial last year. The government previously submitted that the ban would be proportionate even if there was no evidence that it would do any good, arguing that it “was a moral and political judgment which could be supported by intuitive common sense alone.”

Yet, bluntly put, the suggestion that trade in such antique ivory makes a direct or indirect contribution to the poaching of elephants today had not been proven.

Despite dismissing the Friends of Antique Cultural Treasures Ltd’s legal claims, which would require the UK to justify laws that infringe rights, Mr Justice Jay was sympathetic to the ivory dealers’ case, and was at times unimpressed by the evidence relied upon by the UK government.

He remarked, for example, that the government’s case was “somewhat of a mélange of evidential shards varying in their weight” and that certain arguments were “often very strongly held and emotionally expressed, and therefore not necessarily entirely dispassionate.”

1813, Japan, Polychrome woodblock print depicting the traditional Japanese smoking ensemble, pipe, tobacco pouch, and netsuke. Photo by: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The aspect of the appeal of most interest to me is whether the UK courts have failed to take into account the fact that the trading ban undermines fundamental rights—primarily the right to respect for property, and specifically that the ivory-trading ban could never be proportionate without a compensation scheme.

The start point is the first instance judgment. In his ruling, the judge noted that “if this were a case of complete deprivation of a property right, compensation would probably have to be paid in order to render the interference proportionate.”

But he noted that the Ivory Act prevents dealing rather than use, and that the delay in its implementation (it was given Royal Assent in December 2018, but has yet to take effect) gives owners of antique ivory a window in which to sell their holdings—although admittedly “almost certainly at a significant undervalue.”

The judge added that sales outside the UK are probably still permitted under the new law, all of which tempers the degree of interference with antique dealers’ rights. This is significant legally: where someone is fully deprived of their property rights, there is a strong argument that they should be compensated, and case law indicates that it will be exceptional for compensation not to be payable.

By contrast, in other cases—such as the one at hand—ownership is retained, but rights are controlled by the state, and the obligation to compensate is much weaker.

This left the ivory traders having to argue that the very essence of the right to hold ivory had been taken from them. The court disagreed, finding that there was no obligation upon Parliament to introduce a compensation scheme, for three reasons.

First, the court held that there was adequate time between the passage of the act and its implementation for everyone to plan around it.

Second, giving compensation could have a potentially chilling effect on other states considering bans that have no means to offer money to affected parties.

Finally, the court saw no evidence suggesting which dealers would be entitled to compensation, and in what amounts.

A Japanese netsuke. Photo by Artyom GeodakyanTASS via Getty Images.

The principles examined in the ivory-trading case are of importance beyond constraints on controversial products.

Recent history has repeatedly shown UK politicians willing to propose, or in some cases sanction, the seizure of private-sector property. This has been mooted during the Covid-19 crisis, in terms of the nationalization of PPE manufacture and, most recently, future vaccine technology.

The regularity of such exceptional circumstances coming to the fore increases the likelihood of the courts continuing to revisit (and, in my view, expand) the category of cases in which compensation need not be paid to those deprived of their property and its use.

This will be either because a measure, however “expropriatory” in form, is treated as a control of use of property, rather than a deprivation; or because the circumstances fall within the limited—but potentially growing—range of cases in which even an outright deprivation need not be compensated.

All of the above makes it intriguing to see if the ivory-trading case will be granted permission to appeal to the UK Supreme Court. But that will only happen if the application is deemed to raise an arguable point of law of general public importance.

Tom Snelling is a partner at Signature Litigation in the UK.