Opinion

In a Warhol Smackdown at Christie’s, Which $30 Million Work Is the Better Bet?

Only one is truly worth that kind of cash.

Only one is truly worth that kind of cash.

Richard Polsky

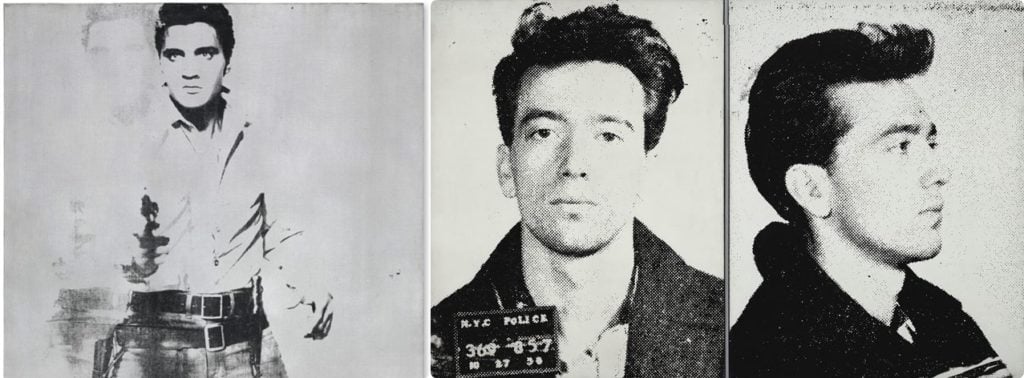

On Thursday, Christie’s will auction off two classic Andy Warhol paintings: Double Elvis (1963) and Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr. (1964). Each carries a pre-sale estimate in the region of $30 million.

Assuming you were comfortable spending that kind of money, which one is the smarter buy? Both have sterling provenances and compelling backstories. But one comes out decisively on top.

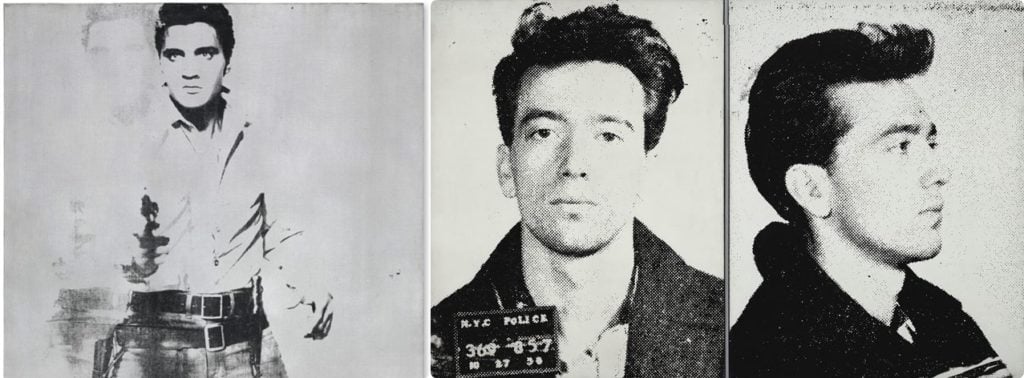

As most Warhol aficionados know, Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr. was an extension of a mural commissioned by the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Under the auspices of fair organizer, Robert Moses, Warhol provided a 20- by 20-foot mural for one of the pavilion’s outdoor walls—the only work of public art he ever made.

Andy Warhol’s Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr. (1964). Image courtesy of Christie’s.

In something akin to genius, Warhol used the venue to silkscreen a group of individual portraits of America’s 13 most wanted men.

However, within 48 hours of the mural’s debut, then New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller—who would go on to be the subject of a Warhol portrait himself in 1967—ordered them removed. Apparently, he was running for re-election and was concerned that seven of the 13 men had Italian surnames. Warhol’s response was to have the portraits painted over in silver.

Amid the World’s Fair debacle, Warhol also produced gallery-size canvases of each of the 13 criminals. (The subject of this one, John Joseph H, Jr, had robbed a liquor store with three accomplices.) A core group of the paintings were displayed for the first time in 1965 at Ileana Sonnabend’s legendary Paris gallery. As one might imagine, they were a tough sell.

The first owner of Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr. was Mickey Ruskin, the proprietor of the bar and beloved New York artist haunt Max’s Kansas City. Chances are that he acquired it in lieu of charging Warhol and his entourage for food and drink.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that the British advertising executive and mega-collector Charles Saatchi recognized the investment potential of the “Thirteen Most Wanted Men” series. During that era, he went on a well-documented buying spree of contemporary American blue-chip art, loading up on early Warhols—including Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr.

Given the painting’s stellar history and wall appeal, would you be wise to spend $30 million on it? Like most things in life, it comes down to your point of reference. If your goal is to own a single quintessential Warhol, an example from the “Thirteen Most Wanted Men” series is not the right picture for you. Instead, Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr. would have far more resonance displayed in a collection surrounded by other important Warhols.

The estimate is also a bit aggressive. To date, the priciest work from this series to sell at auction fetched $4.7 million with premium in 2011, according to the artnet Price Database. By contrast, this same Double Elvis sold at Sotheby’s in 2012 for $37 million with premium (on an estimate of $30 million to $50 million), above the current expectations.

But let’s assume that your collection contains other world-class trophies—which is entirely possible for a buyer of a $30 million picture. Are you then better off with one of the “Thirteen Most Wanted Men” rather than an Elvis? Probably not. Simply put, Elvis Presley is a “top ten” iconic figure of American popular culture.

During the trial to determine the fate of Warhol’s estate, the prominent dealer André Emmerich, who once represented artists Sam Francis and David Hockney, was brought in as an expert witness on behalf of the Warhol Foundation. In a surreal debate, Emmerich argued that Warhol’s estate had been overvalued. (The foundation was likely seeking to lower its payment to a lawyer originally hired to settle the estate, who was being paid a percentage of its total value.)

André Emmerich testified that the value of Warhol’s work was likely to fall in the future. His reasoning was that Warhol’s celebrity portrait subjects—specifically Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Elvis Presley—would soon be forgotten. It’s hard to determine what Emmerich was thinking. Since that trial, Elvis has been honored by not one, but two, United States postage stamps.

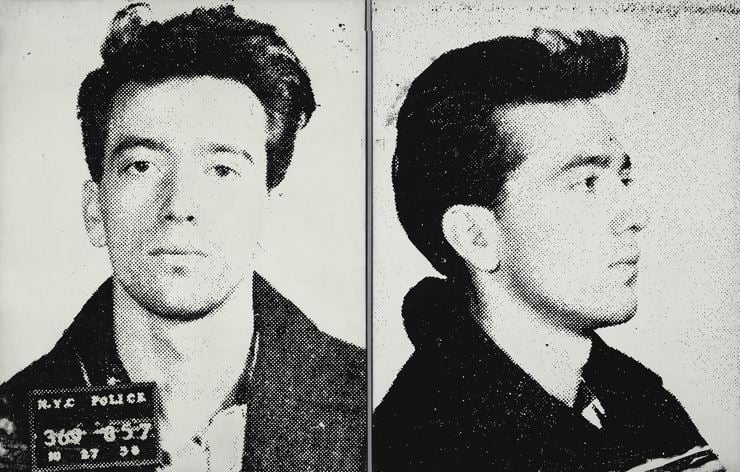

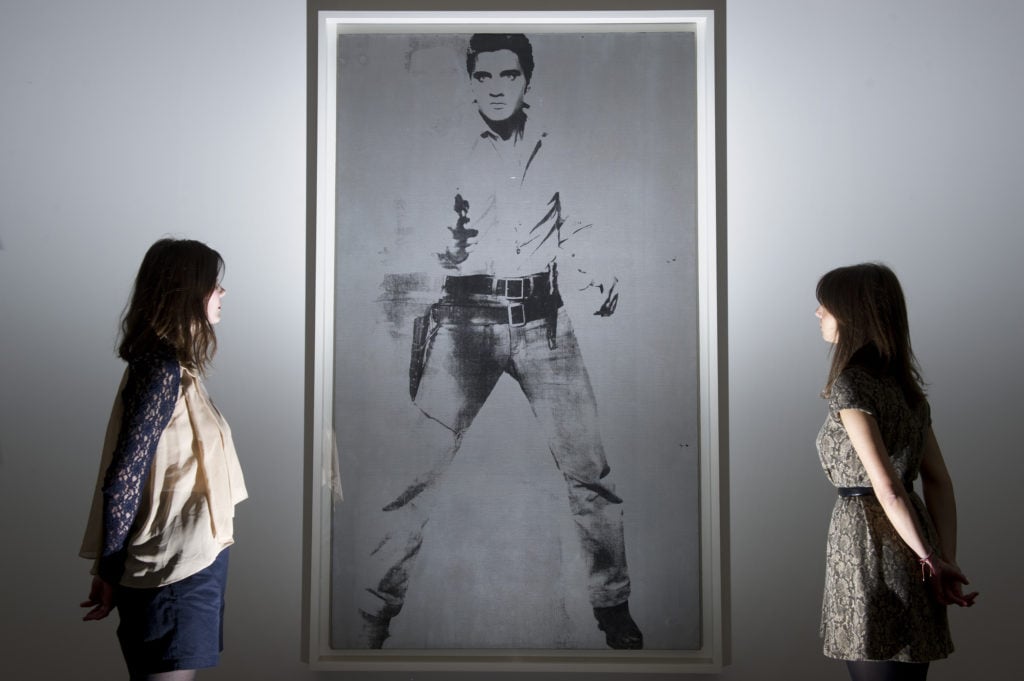

Steve Wynn had bought Warhol’s Double Elvis [Ferus Type] at Sotheby’s in 2012. Photo credit: CARL COURT/AFP/Getty Images)

Double Elvis, just like Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr., has a stellar provenance. Besides the Ferus Gallery, it passed through the Leo Castelli Gallery and was once sold by Ileana Sonnabend. It is now reportedly being sold by casino mogul Steve Wynn (who recently withdrew two other works from this week’s sales). It remains to be seen how the embattled figure’s ownership may affect its sale price.

The painting itself, however, has more than provenance in its favor. The composition is also perfectly “cropped.” It was originally shipped to Ferus Gallery as part of a roll of continuous Elvis images. Warhol, ever frugal, decided he could save a fortune by not sending fully stretched paintings. When the roll arrived in California, he gave his dealer Irving Blum vague instructions over the phone for how to cut the images into individual works. Blum got this one just right.

Although naysayers have said that the faint “double” impression of Elvis behind the central figure makes it less than a stellar example of a “multi-Elvis,” in some ways the ghostly quality of the second image makes the whole thing more compelling—inviting the viewer back again and again.

So, is the aura of Elvis enough to carry the day over the portrait of an obscure hoodlum? The ultimate reason that Double Elvis represents a better value today, and an exponentially greater value in the future, is because the direction of the art market. You now have countries (like Qatar), along with private museums and foundations founded by billionaires keen on tax advantages, buying the most expensive art available. These buyers will always insist on acquiring works of art that validate their station in life.

Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr. is a significant Warhol. But it is not a classic celebrity picture. Whether a mega-wealthy collector is sophisticated or not, he (or she) will pay whatever it takes for a work synonymous with the great Pop artist.

At least one buyer seems to agree with me. Unlike Most Wanted Men No. 11, Double Elvis boasts a third-party guarantee, meaning that an individual has effectively pledged to buy the work at an agreed-upon price ahead of the sale.

I’m with Mick Jagger, a Warhol subject in his own right, who once sang in the tawdry ballad, Cocksucker Blues: “I don’t have much money but I know where to put it every time.”

Richard Polsky is the author of two books by Andy Warhol, I Bought Andy Warhol (2004) and I Sold Andy Warhol (Too Soon) (2011). He is also the owner of Richard Polsky Art Authentication, which specializes in authenticating the work of Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Keith Haring.