Art Criticism

Here Is What the Riddle at the Heart of the 2022 Whitney Biennial Actually Means

A philosophy unites the show's many enigmas—but it wants you work to uncover it.

A philosophy unites the show's many enigmas—but it wants you work to uncover it.

Ben Davis

In an official interview about the 2022 Whitney Biennial, David Breslin, who co-curated this show along with Adrienne Edwards, explains the duo’s overall ambitions. “There’s a phrase that we toss around a lot: ‘buck wild,’” Breslin says. “It needs to be weird. It needs to press something. It needs to be authentic and genuine to an aspirationally wild mind.”

It’s a striking quote, mainly because, well, you’d never guess that this is what they were shooting for. The Biennial has its weird moments (most notably a characteristically gnarly Pop Surrealist video installation by Alex da Corte). But like all big art shows in the U.S. recently, its dominant tones are reverent and restrained, its themes ethical and memorial.

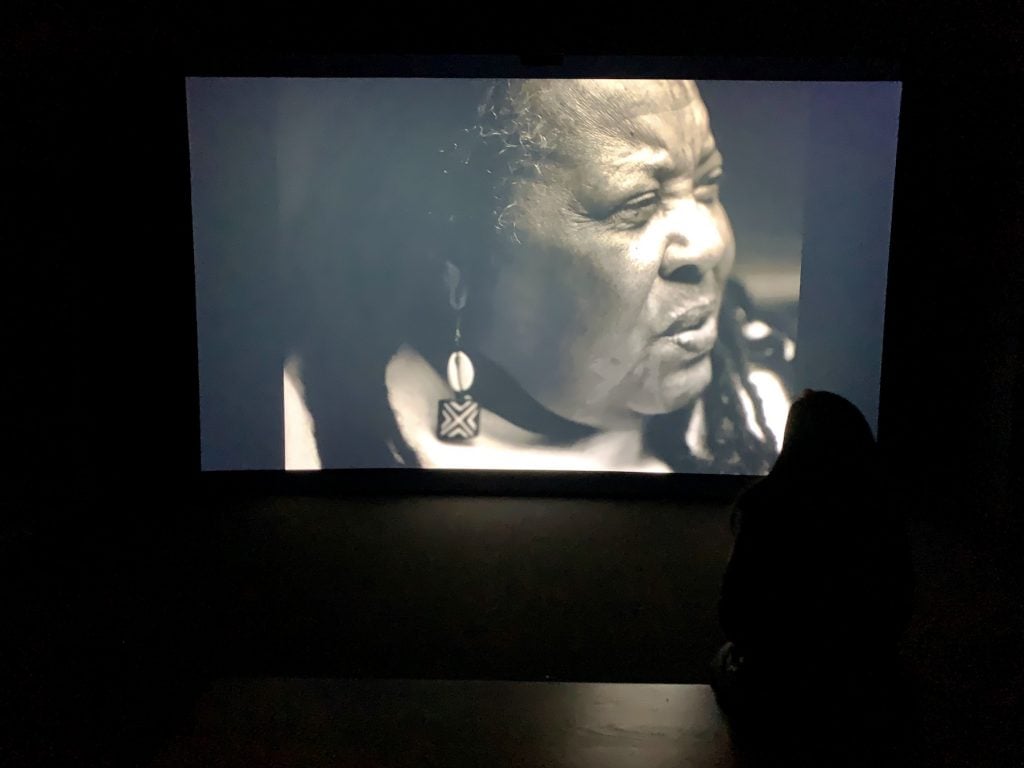

This Biennial’s major touchstones range from wryly didactic conceptual art (Rayyane Tabet, Emily Barker) to practices of ritual mourning (Coco Fusco, Mira Na), and from melancholy sci-fi surrealism (Daniel Joseph Martinez, Andrew Roberts) to an awed, hour-long documentary honoring a Civil Rights spiritual leader (Adam Pendleton’s Ruby Nell Sales).

Adam Pendleton, Ruby Nell Sales (2020-2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

I mean, the show is called “Quiet As It’s Kept.” If there is a “vibe shift” in culture going on towards the irreverent and the ironic, it’s not happening at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

It’s interesting to think about why this show has to feel the way it feels, and whether it has split intentions. But whatever else you can say about it, the 2022 Whitney Biennial is rewarding—if you give it the time that it demands.

I’m not going to say a lot about the distinctive installation of the show, since a lot of the reviews so far have harped on it. What I will say is that I am on the curators’ side: I think it’s inventive, and I think it all has a point.

James Little, Borrowed Times (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

On the 5th floor, walls have been removed, with paintings shown on free-sanding partitions scattered around the space, in a slightly disorienting way. This device has drawbacks in terms of audio works, but it works symbolically, since one point of the show is to free art up from some fixed habits of seeing. On the 6th floor, by contrast, everything is painted black and there’s lots of video. This works too, since another point of the show is the need for commitment, care, and attention.

What I will talk about is the centerpiece of the show on the 6th floor: an empty black gallery that serves as a riddle for its deepest themes.

A vial is shown beneath a spotlight in a clear display box. It is “Thomas Edison’s Last Breath,” per a wall label (the vial is on loan from the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan). The text also relays the story of the odd object—Henry Ford admired Edison so much that he had a friend bottle his dying breath—without explaining why it is here or what it means.

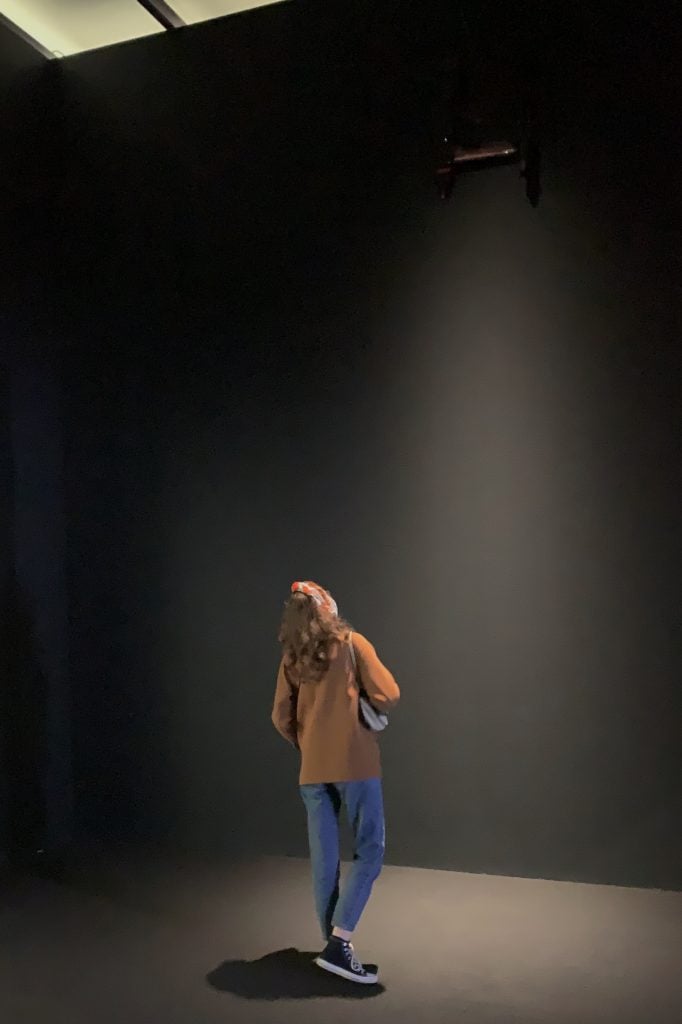

A visitor looks at a vial containing “Thomas Edison’s Last Breath.” Photo by Ben Davis.

The soundtrack to the room is an audio work by Raven Chacon, the experimental composer whose inventive spins on the musical score as a concrete poem are shown as visual art one gallery over. His audio environment here is, in fact, just a collection of sighs and sounds of moving air. Chacon recorded it during the Standing Rock protests in 2016, at a silent demonstration led by women—a political play on John Cage’s 4’33”.

Finally, high up on the wall opposite the Edison vial, hidden by a light and impossible to see, is a mystery object, not even marked with a label. Edwards, at the press call, suggested it related to the Black experience in the United States. A page from the catalogue dedicated to this mystery room has Breslin say, simply, “It’s story is not mine to tell.”

A visitor views a mysterious object that is part of the 2022 Biennial but left unlabeled. Photo by Ben Davis.

So, you have a ghoulish relic celebrating a history defined by the relations of wealthy white men and industrial power. And around it, a silent Native presence and a hidden Black presence. In that puzzle you have an entire theory of cultural importance and artistic mission.

But most importantly, the show doesn’t want to come out and tell you what’s on its mind. You are being asked to do work to get to the bottom of it.

With this room in mind, the more you dig into “Quiet As It’s Kept,” the more you find that it is teaching you to distrust what you see, and think about what you don’t.

This is very clear in Guadalupe Rosales’s suite of lucid photos, showing becalmed sites in East Los Angeles, their emptiness haunted by the fact that they are where people close to her were killed.

A visitor interacts with Alejandro “Luperca” Morales, Juárez Archive (2020-ongoing). Photo by Ben Davis.

It’s true in another way of Alejandro “Luperca” Morales’s Juárez Archive, which lets you see important sites in his hometown of Juárez, Mexico, inset in little plastic view finders that you have to pick up to peer into. This archive was made under Covid restrictions that kept Morales from his home, so the images are from Google Street View—real memories strained through found images.

In Lucy Raven’s video, you are shown a sequence of nondescript desert landscapes. Off-camera, explosions go off. Blast waves slowly unfurl across the image, in super-slow-mo. What you see are just the effects of cataclysmic force that you don’t see.

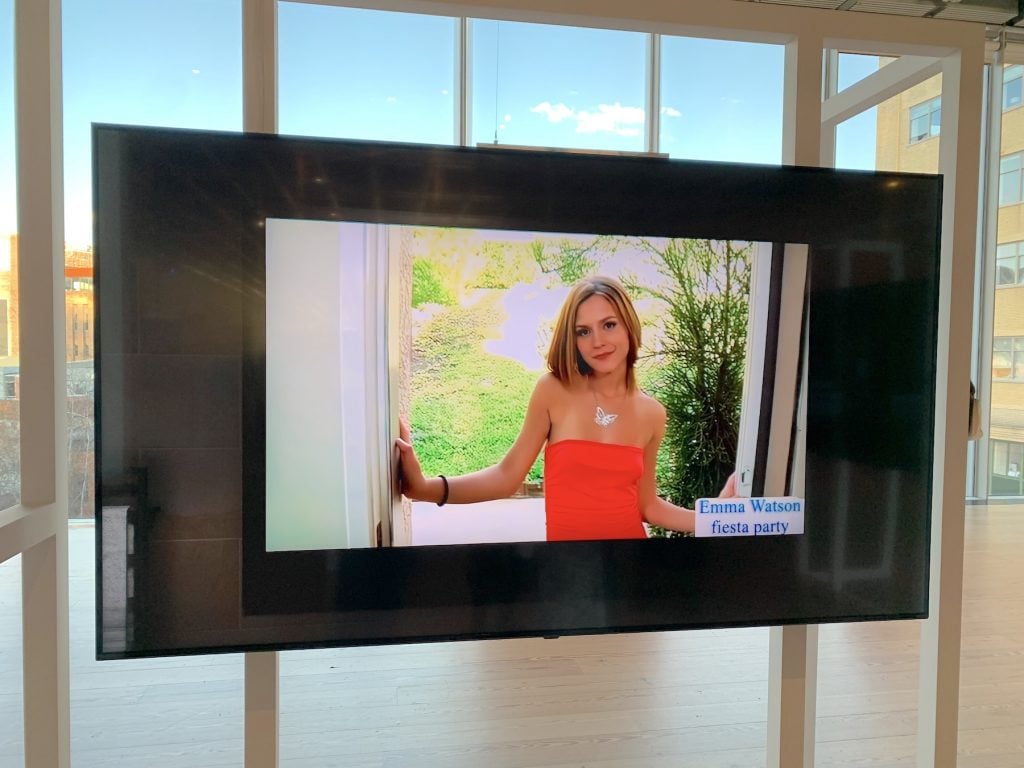

Jacky Connolly’s Descent Into Hell creates a dream narrative, shifting between aimless, surreal vignettes starring mostly female background characters from the famously ultra-violent video game Grand Theft Auto, then cutting briefly to AI-augmented deepfake footage of Harry Potter actress Emma Watson spliced into an adult film. It’s as if you are watching an invisible spirit searching for an avatar to inhabit, but never coming to rest, discovering instead how broken and corrupted digital reality is.

Jacky Connolly, Descent Into Hell (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

More affirmative is Jonathan Berger’s An Introduction to Nameless Love. This is a gallery full of freestanding panels made of gleaming brass text, each an account of a different intense, life-altering instance of non-romantic love. For instance, the text titled “The Empress” tells of how a connection with a captive turtle, glimpsed in a tank, transformed into a life-long advocacy for turtles.

Again, the Biennial intentionally cuts against immediacy. Only three or four people are allowed into the Berger space at a time to read literal walls of words, which demand time to absorb and decode, to fit together a voice, a story. By displaying them as sacred texts, Berger is asking you to treat these unconventional stories with care, not consume them as outlandish novelties.

Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love (2019). Photo by Ben Davis.

Here, you can also feel the thoughtful program the curators have set themselves butt up against what the Whitney actually is as an entertainment machine: having spent 10 minutes or so waiting in line, you suddenly become very conscious of how long you are lingering in Berger’s environment, as people glower at you, waiting their turn.

There is a lot of video in the show. It requires a serious investment of time and attention—a fact which, I think, is another variation on the theme that the show wants you to commit to think with it.

Trinh T. Minh-ha, What About China? (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

Trinh T. Minh-ha’s alt-doc What About China? (2020–21) lingers across more than two hours. Her voiceover reflects on how during the pandemic, she found new significance in images she took during a trip to China in the early 1990s. She asks questions about the fate of the peasantry amid the country’s historic transformation, offers examples of folk songs, and reflects on the meaning of Chinese architecture and classical Chinese landscape painting. It’s a massive, complex web of a video essay.

Kandis Williams, Death of A (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

Kandis Williams’s 27-minute Death of A (2022) offers a brooding, four-channel video that has a Black actor recite Willie Loman’s tragic monologues from Arthur Miller’s mid-century “Tragedy of the American Dream” play Death of a Salesman, stripped of that opus’s specific narrative. Archival clips of mushroom clouds, U.S. military training, protest, and Black pop culture play on an opposite screen, filling it up with conflicting new associations.

In a ground-floor gallery made to feel like the hold of a ship, the art collective Moved by the Motion (Tosh Basco and Wu Tsang) riffs on another Lit 101 classic, Moby Dick.

Fred Moten in Moved by the Motion, EXTRACTS (2022) in the Whitney Biennial. Photo by Ben Davis.

It is a lush, narrative-less 36-minute montage of free-floating, dancerly vignettes, with model-like actors portraying the crew of the Pequod (it also has a cameo by Fred Moten, the poet-philosopher known for his thinking about the need to claim opacity as a political virtue, cast as a sorcerer-like figure). Moved by the Motion’s film aims to tease out Melville’s queer, anti-colonial, and ecological resonances, bringing them closer to the surface.

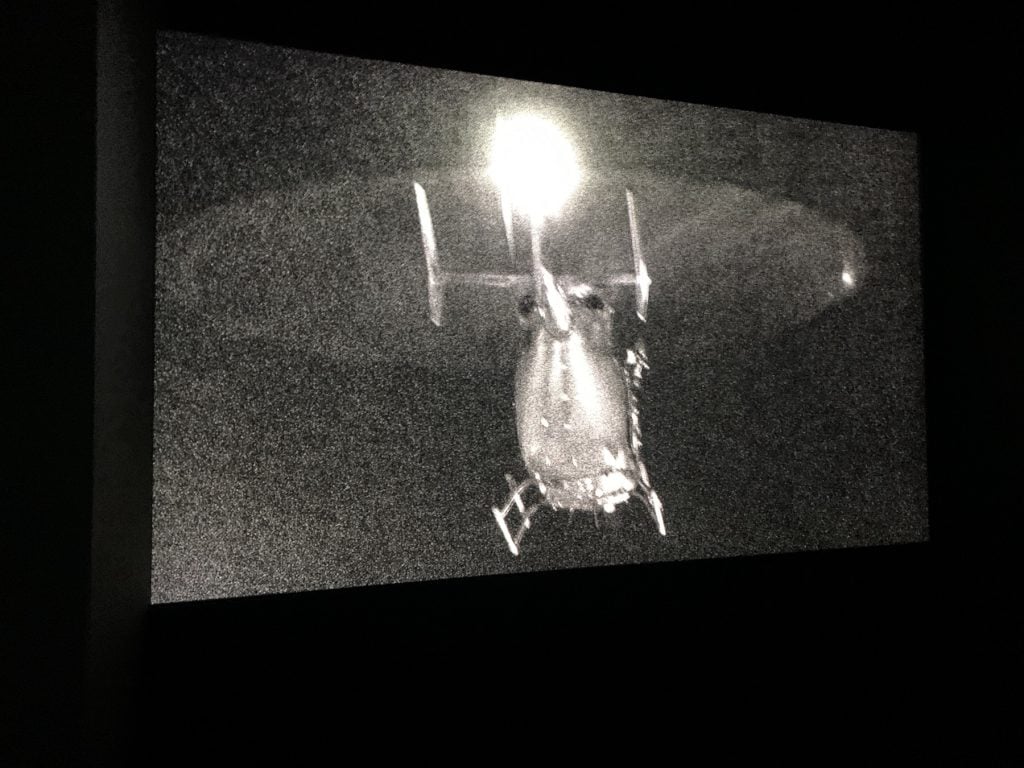

An outlier in “Quiet As It’s Kept” is Alfredo Jaar’s video installation. You enter the darkened gallery where the film plays at certain regular times, like a ride. Within, you see vivid imagery of an incident during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in Washington, D.C., when demonstrators were terrorized by helicopters that descended frighteningly close to them.

Image from Alfredo Jaar, 06.01.2020 18.39 (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

Jaar has implanted the ceiling with industrial fans that come on as the onscreen helicopters descend, intensifying as the action mounts. Hair and clothes whip around. The roar of the fans becomes deafening.

Jaar has said that he knew he had to create an experience that was under five minutes, because of the vanishingly short attention spans of the contemporary art audience. In other words, the work is designed to do exactly what the entire rest of the show, with its focus on fragmentation, indirection, and hard-earned reflection, is meant not to do: Give you a visceral, clear, and easy-to-grasp political epiphany.

When it comes to painting, abstraction is the order of the day.

The turn toward abstract art in this show continues a trajectory begun by the 2019 Whitney Biennial. There, a rhetoric of retreating from visibility already manifested, even in figurative work like Jennifer Packer’s painterly, semi-abstracted portraits of Black subjects—a device curator Jane Panetta explained by saying, “by not giving over fully to the viewer, that becomes this protective gesture and even a way to keep some of the intimacy to these sitters.” (Packer’s great Whitney survey on the 8th floor closed just as the Biennial opened.)

The curatorial turn seems readable as a reaction to the market dominance of figurative art featuring Black subjects, or queer themes, and an uneasiness with the resulting sense of the voracious consumption of identity as a product or as a too-easy symbol of social justice. In this way, the sheer space given to abstract painting here dovetails perfectly with the Biennial’s larger theme about the ethics of looking.

Awilda Sterling-Duprey, …blindfolded (2020-ongoing). Photo by Ben Davis.

In “Quiet As It’s Kept,” the key artist on this level may be also the most senior figure: Awilda Sterling-Duprey. The Afro-Puerto Rican artist makes energetic, convincing abstractions, shown in the space at the center of the sunny 5th floor galleries. Her recent series of “Dance Drawings” are made while blindfolded and listening to jazz, in a kind of creative ritual of embodied art. Video of her performing is shown on the reverse of the scaffolding displaying her canvases here.

Through one eye, you see her paintings as engaging explosions of color on canvas; through the other, you have the living body of the artist behind the canvas, foregrounded.

Almost all the abstract art here is by artists of color and/or queer artists. The show puts me in a strange position in that it feels weird to mention this, but also weird not to mention it. Obvious markers of identity are absent in the paintings themselves, but each work is carefully described as being incomplete on its own, visually, without some knowledge of the cultural background of the artist in question.

Denyse Thomasos, Displaced Burial/Burial at Gorée (1993). Photo by Ben Davis.

Lisa Alvarado’s zigzagging “Vibratory Cartographies” are gorgeous on their own terms, but their dynamic yet precisely structured landscapes of color are also presented in relationship to Mexican American craft traditions and her own family’s migrant experience.

Rick Lowe’s big canvas crisscrossed by tendrils of black and white is meant to reference playing dominoes, itself a metaphor for the street life he has otherwise engaged with as a community-building artist in Houston’s Third Ward.

The late Trinidadian-Canadian artist Denyse Thomasos’s show-stopping, densely cross-hatched paintings from the 1990s are meant to reveal themselves as anxious, abstract diagrams of slave ships and prison architectures.

Dyani White Hawk, Wopila | Lineage (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

And all this makes sense. It’s nonsense to think that the cultural background of Jackson Pollock or Frank Stella or any of the other big U.S. white guy painters wasn’t always present as part of how people interpreted what they did—it was just so securely at the center that no one bothered to interpret it. A lot is hidden in that historical silence: As a matter of fact, Dyani White Hawk’s beautifully beaded shimmering geometry, a highlight in this Biennial, is intimately engaged with Lakota craft traditions but also explicitly presented as a reminder of how the heavies of mid-century Abstract Expressionism took inspiration from Native American art.

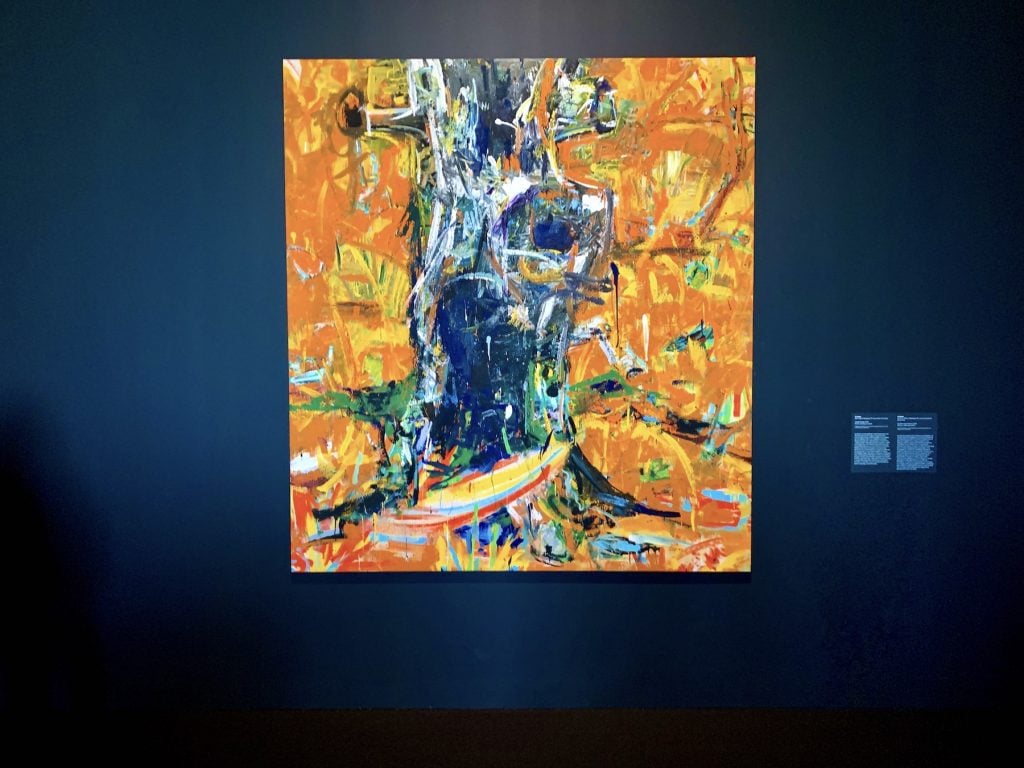

But consider a painter like the young art star Cy Gavin. He’s sometimes in the past been known for oneiric figuration that channels traditions from Bermuda, but is represented here by a painting that may be a tree, abstracted to illegibility, against a churning orange background. “Gavin, who grew up in Donora, an industrial town in Pennsylvania’s Rust Belt, is of African-Caribbean ancestry,” we read beside his canvas, Untitled (Snag). “His work personalizes landscape and embeds it within a particular time. Landscape becomes an engine to explore the subjectivity of the person who paints—and sees—it, as well as the histories each of us brings to that encounter.”

Cy Gavin, Untitled (Snag) (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

The two halves of that thought aren’t really pinned together, as if the author themselves was unsure why they were stressing Gavin’s ancestry as key to interpreting this particular work, maybe sharing my feeling that this show’s framing makes it seem reductive to mention and evasive not to mention. (Hilton Als, for one, reads Gavin’s landscapes through the lens of Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Hudson River School sublime.)

It feels as if there is something unresolved in the thinking about embodied abstraction in “Quiet As It’s Kept”—but maybe that is just the kind of tension the show wants us to linger on.

If there is one absent presence whose thought explains the texture of Breslin and Edwards’s Biennial, it is the artist David Hammons.

Known for his riddling conceptual takes on Black culture and deliberate frustration of audience expectations, Hammons happens to be one of the sources of the title “Quiet As It’s Kept”—this was the name of a show of abstract art he curated back in 2002, featuring artists (including Denyse Thomasos) “attempting to evade the gaze of those who would police the definitions of ‘black’ art.” Whatever the unknown object suspended in the darkness on the 6th floor is, its inclusion is certainly a very Hammons-like gesture of cultivated mystery.

And the key text of this show is also by Hammons. It’s present, but fittingly hard to find. It comes in a suite of videos by conceptual video-maker Tony Cokes, shown near a window alcove on the sixth floor. In Cokes’s almost parodically dry style, these videos are like a test of your patience: deadpan, horizontal panning shots across a waterline, overlaid with scrolling texts quoted from fiction or academic theory that riff on the politics of the image.

Tony Cokes’s video featuring text by David Hammons at the Whitney Biennial. Photo by Ben Davis.

Stick around through the nearly 50 minutes of scrolling text, and you get a famous 1988 interview with David Hammons—one of the great artist interviews, a rare open statement of method from an artist who avoids explanation. These words fly past:

[A]rt has gotten so…I don’t know what the fuck art is about now. It doesn’t do anything. Like Malcolm X said, it’s like novocaine. It used to wake you up but now it puts you to sleep. There’s so much of it around in this town that it doesn’t mean anything. That’s why the artist has to be very careful what he shows and when he shows now.

You can think of this Biennial’s difficulty and hyper-sensitivity to context-building as an attempt at generalizing this insight, reflecting today’s even more general sense that art’s audience is deadened to the deep meaning of images, primed for hot takes and reductive snap judgments. But it’s a real challenge to do that in an institution and at an event whose very job is to add to the feeling that there is “so much art around.”

These are times of deep uneasiness with power structures, including those found in museums, even as Black artists, Indigenous artists, queer and trans artists, are being foregrounded at unprecedented levels. So, you get a rhetoric of difficulty, of holding space but also retreating from legibility.

Whether the resulting in-its-head atmosphere connects with the “aspirationally wild minds” of today, I don’t know. But if this Biennial doesn’t feel quite like it can let itself go fully wild, there is also a quiet weirdness to it that sincerely reflects the disorienting headspace of the present, and that is worth the trip.

“Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept” is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, April 6–September 5, 2022.