Art World

How Maverick Artist Cy Gavin Painted His Own Way From Bermuda to the Rubell Foundation

Founding his own space and retreating Upstate, Gavin has created his own path.

Founding his own space and retreating Upstate, Gavin has created his own path.

Terence Trouillot

He’s a rising star now, but the young Cy Gavin never thought he would become an artist. “To be an artist, for me, meant that you came from immense privilege,” he told artnet News. “I just loved art.”

Now Gavin has two sold-out solo exhibitions at Sargent’s Daughters under his belt, one in 2015 and one 2016, and is featured currently at the Rubell Foundation in Miami. Next year, he’ll be in Paris: He’s currently working with Victoire de Poutalès and Hélène Nguyen Ban, the gallerists behind VNH Gallery, for a show of new works in February 2018.

Gavin is best known for his stunning and beautiful paintings that are all motivated from personal experiences and his relationship to his family, his past, and the medium itself.

He draws inspiration from Bermuda, the homeland of his father, and a place the artist has often visited to conduct research on his family’s history. His art incorporates the country’s flora and fauna, as well as its complicated history as a pivotal site during the transatlantic slave trade, and as the first island in the Atlantic to attract wealthy American tourists seeking an alternative to summers in Europe during in the 1920s.

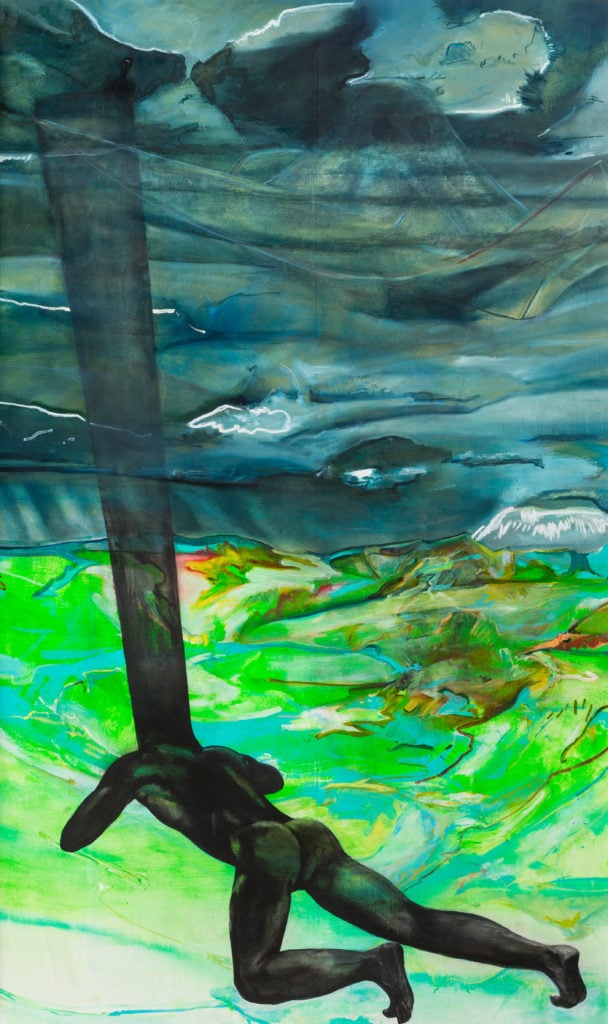

Cy Gavin, Between Heaven and Earth (2015). Image courtesy the artist.

“I was surprised when I went to Bermuda for the first time—the history of slavery there is invisible, even though it’s omnipresent,” he explains. “There are brown people everywhere. There’s no trace of it. No mention of it in the historical society. They have every detail of colonial life with no mention of black people.”

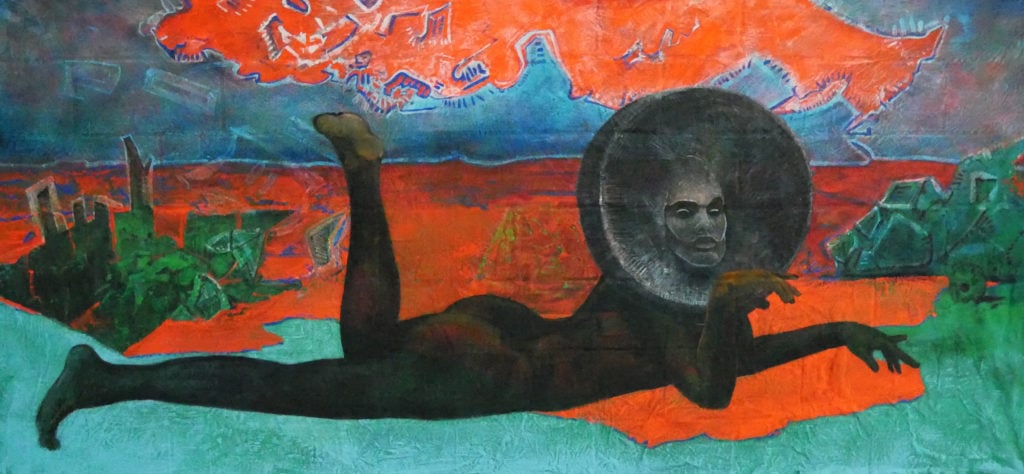

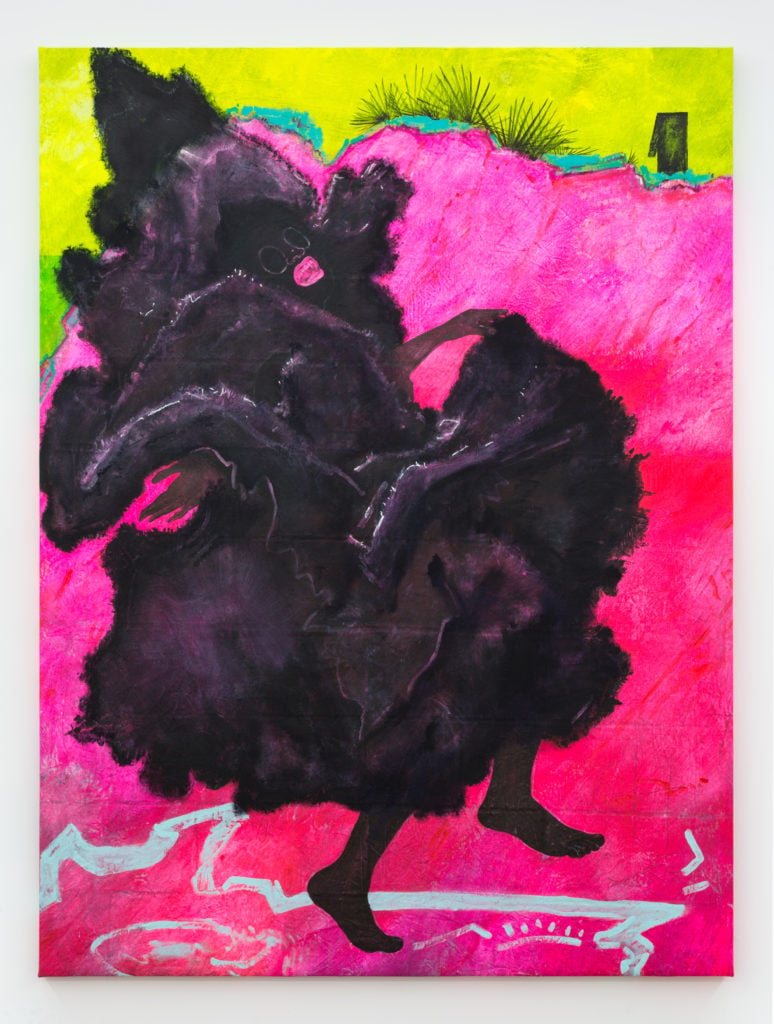

The works are intricate. These colorful, enrapturing paintings, using acrylic and oil paint, render loosely abstracted landscapes, often incorporating dark black figures—phantom-like beings who become the centerpiece of each work. The results are stark, arresting, strange, and imaginative.

The poses of Gavin’s figures are inspired by the dance traditions of the Caribbean and Bermuda. He has also taken to incorporating some of the natural materials he collected in Bermuda into his paintings (e.g. Bermudan pink sand, irises, etc.).

Cy Gavin, Tucker’s Town (2016). Image courtesy the artist.

Gavin grew up in Donora, Pennsylvania, 20 minutes south of Pittsburgh. A Rust Belt town, Donora was home to a lot of heavy-industry, including steel-making and coal-mining. Both his mother and father worked at glass factories; his mother still does to this day. He was also raised Jehovah’s Witness, and often traveled with his father going door to door to do missionary work. Bored from the monotonous routine, Gavin would sit in the car reading and drawing while his father was doing the “Lord’s work.”

As a teenager, Gavin fell in love with art and drawing, regularly going to Carnegie Museum of Art in nearby Pittsburgh. “I spent my entire childhood in that museum,” he says, emphatically. “I couldn’t afford to go in—it was like $13 a ticket ($12 for kids today)—but there’s a way through the library there [connected to the museum], where you take the elevator down to the basement and go through the stacks and pop into the museum.”

Cy Gavin, Indian John Laughing at Gibbet Island (2016). Image courtesy the Rubell Family Collection.

Yet despite graduating from Carnegie Mellon University with a degree in art in 2007, and continuing to paint and make videos, it wasn’t until 2011 that Gavin decided he wanted to become a serious artist.

After a brief stint in San Francisco following his graduation from CMU, Gavin moved to New York in 2011 and started working with Lia Gangitano at the Lower East Side non-profit stalwart Participant Inc. He worked in development, and still helps maintain the gallery website.

Cy Gavin, Marsden Cemetery at Tucker’s Point (2017). Image courtesy the artist.

Soon thereafter Gavin began assisting artist and filmmaker Ellen Cantor on her project Pinochet Porn (Cantor’s last film before she passed in 2013), and worked as an archivist for Vito Acconci’s studio. He was heavily influenced by both artists, mentioning in particular Acconci’s shape-shifting character and incredible work ethic. “He was the hardest working person I’ve ever known.”

Gavin was accepted to Columbia University’s MFA program in 2014, where he worked closely with artists such as Fia Backström and Sanford Biggers, and art historian and curator Kellie Jones, whom Gavin considers his mentor.

Cy Gavin, Rosewood Tucker’s Point Golf Club and Cemetery (2016). Image The Rubell Family Collection.

“I wanted to be treated as an autonomous person who’s responsible for my time there,” he notes, “and Columbia was that way. You could do nothing and graduate or you could kill yourself and graduate. It was like you build your own adventure.”

At Columbia, Gavin opened a secret gallery in an abandoned building in East Harlem owned by the University. “It was a former locker room and shower,” he said. “And I asked Lia [Gangitano] to curate the show with two sculptors, Ektor Garcia and Michael Blake. I brought electricity, and air conditioning. I painted the walls white. It was a real gallery. And I was caught and got in trouble. But no one knew about the gallery until ARTnews did a story about it.”

The space was called The Can, and although short lived it caught the attention of the school’s faculty, students, and the art world.

After completing his MFA, Gavin was invited to be part of a six-month studio residency program at the Rubell Foundation in Miami. There he created a suite of works that drew inspiration from his time visiting Bermuda and driving through the South from New York to Miami, which are on view currently in “High Anxiety: New Acquisition,” at the Rubell Foundation Collection museum (though August 25).

These also draw inspiration from research into the advent of makeup and cosmetics during the time of Queen Elizabeth. “I hadn’t really thought of the colonial period as having vestiges of Elizabethan era,” he mentions. “It was the first time makeup was being invented to articulate difference. Makeup created a language around color and skin color, allowing character traits to be attached to color. Culture being shifted by the language of color is weird and painty to me.”

Cy Gavin’s studio in Dutchess County, New York. Image courtesy the artist.

Last November, Gavin moved his studio from his apartment in Manhattan to take up shop in a two-story barn just two hours north of the city in Dutchess County, New York. Once abandoned and filled with car parts and wasp nests, now the studio is a tricked out space with a curved leather sofa, a TV, acoustic Victor phonograph, and a sun-drenched studio upstairs where the artist has ample room to work on his large-scale paintings.

“I paint with my body and not my wrist,” he says, describing his process of creating his paintings. Recently, Gavin has been creating wands out of metal tubing to extend his brush, inhibiting some control on his mark making, but gaining more distance from the canvas to think compositionally and engage with the entire surface of the painting.

He’s currently working on next year’s show for Paris, though the gallerists have given him no limits, and he doesn’t know yet what form the show will take.

Cy Gavin’s studio in Dutchess County, New York. Image courtesy the artist.

“All the things I make are ad-libbed,” he told artnet News. “I have a general idea of what I’m doing but I’m figuring that out by looking at the work. I do everything in real time, and it takes me a long time to make paintings.”