A lot is riding on the upcoming Supreme Court case focused on Pop artist Andy Warhol’s use of a photograph of the musician Prince made by Lynn Goldsmith. Was the use fair, creating something new of cultural value, or was it nothing more than bald copyright infringement? In addition to the briefs filed by the Andy Warhol Foundation (the “Foundation”) and Goldsmith, more than 36 different amicus curiae, or friends of the court, have asserted their interest in the outcome through legal briefs.

These include contemporary visual artists, major artist foundations,, and museums across the U.S., but also documentary filmmakers, writers of fan fiction, multiple art law and copyright law professors and libraries and archives. Additional briefs are from a number of self-styled intellectual property legal groups, news media photographers, the Motion Picture Association of America, SAG-AFTRA (the union representing television and film actors and other media professionals), the recording industry, and Republican Senator Marcia Blackburn from Tennessee (home of the Nashville country music industry), and a licensing trade group. (All amicus briefs can be found here.)

Each of these groups has its own interests to advance—artistic, economic, intellectual, and beyond. Much focus has been trained on Warhol as a celebrity artist, a seeming proxy for the big-money art world. But from the copyright perspective, what applies to Warhol applies to every artist, and that is the problem with deeming Warhol a mere “celebrity plagiarist,” as the Second Circuit did. Warhol is of course only one of countless artists who use pre-existing material for conceptual reasons, to make new work. That is why the test for one artist’s fair use of another’s material is not how much more fame or money the second artist acquires, but whether the later work produced adds something different to our culture by transforming its source material.

It is also important to understand that truly big money circling the edges of this fair use case is circulating outside the art world. Standing behind the individual photographer asserting that Warhol improperly used her image is a very large licensing industry. Consider that the global art market was estimated to be worth $65 billion in 2021, with the U.S. accounting for just over 40 percent of that (about $28 billion). Collectively, the global entertainment and media market is reported to be worth more than $2 trillion last year, with the motion picture industry self-reporting $226 billion in sales. Also filing an amicus brief? The Digital Media Licensing Association.

Licensing is a steadily concentrating and maturing industry, substantially (but not exclusively) made up of private players. While Shutterstock has continued to acquire companies over time, Getty Images went public just this year with an initial market cap of close to $5 billion.

All this while the world is flooded with digital images: Instagram users upload on average more than 100 million photos per day, or more than 1,000 photos per minute, existing everywhere at once. There are reportedly 500 million daily active users on Instagram, and 1 billion monthly active users. It is easy to understand the concerns of creators who fear that their works risk becoming lost and devalued in this context.

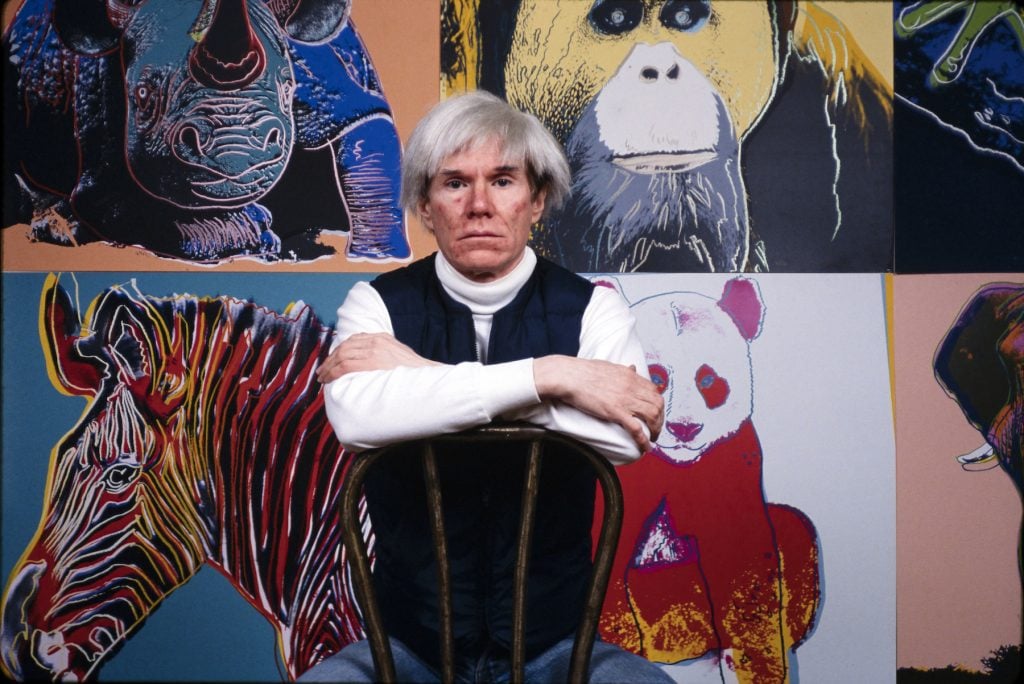

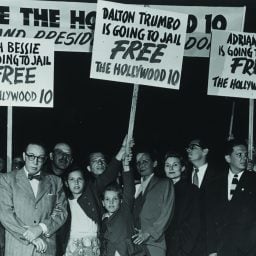

Andy Warhol, Unidentified Photographers (ca. 1981). The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; © 2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

But of these many amicus brief writers, only one is a friend with benefits. The United States government, represented by the Solicitor General (“SG”), is entitled to ask to participate in making oral arguments to the Court when it hears the case this month. The SG is an influential position, sometimes referred to as “The Tenth Justice.”

In this case, the SG speaks primarily on behalf of the U.S. Copyright Office, and on the face of the brief, in support of Goldsmith. However, the text of the brief itself betrays what seems to be real unease in dismissing the Warhol Foundation’s assertion that the artist was exercising his right to fair use of another’s copyrighted material when he created his “Prince” series.

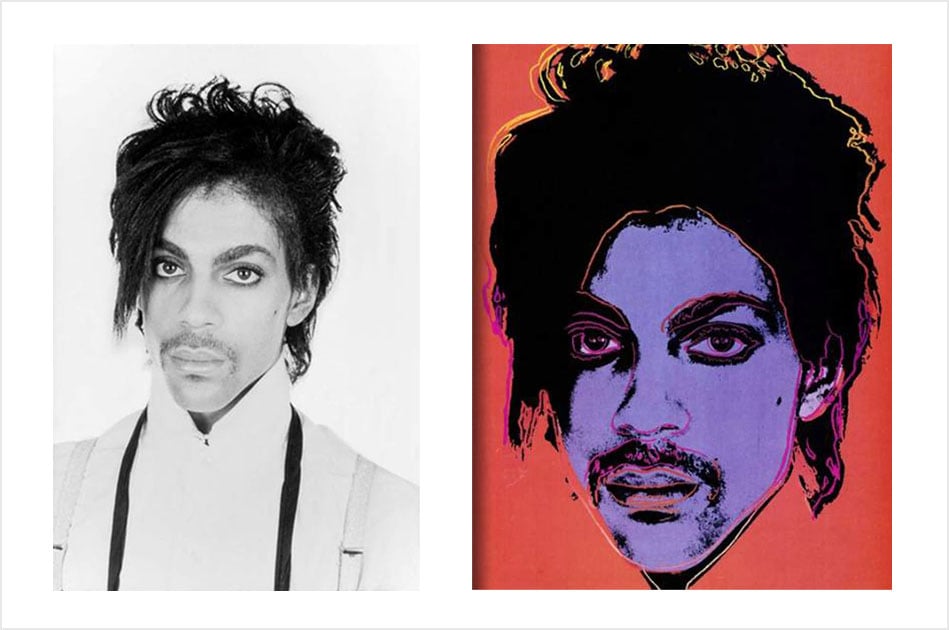

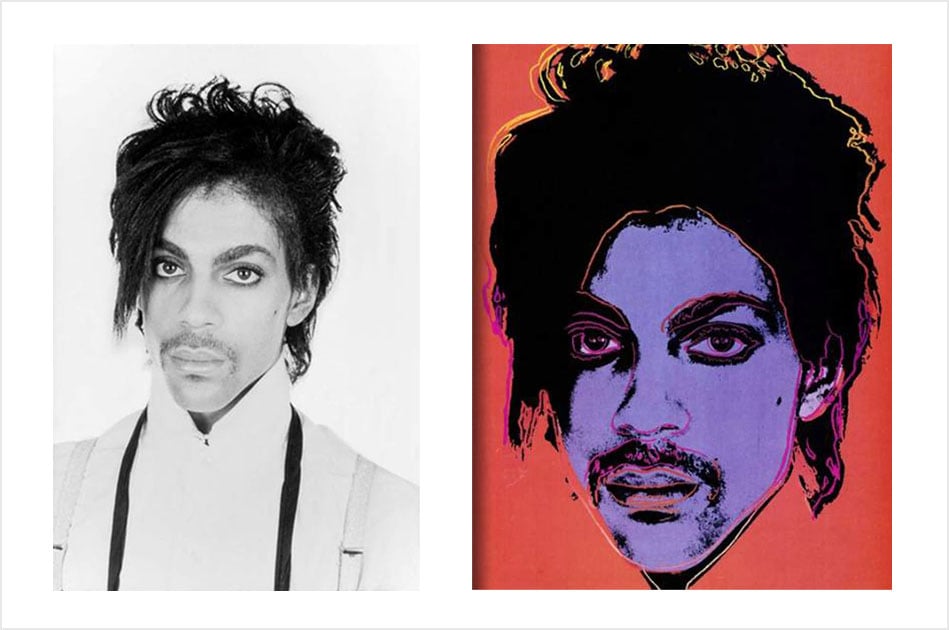

While the parties and amici have different perspectives on the legal issues before the Supreme Court, there is no real dispute about the underlying facts of the case: Goldsmith licensed her photo of Prince as an “artist reference” for use by another artist to create an image to accompany “Purple Fame,” an article that ran in Vanity Fair magazine in 1984.

A few particular facts are of interest here. Vanity Fair did not license Goldsmith’s photograph to illustrate the article, because as the record shows, the magazine wanted Warhol’s creative take on the rising star. Additionally, there was no license directly between Goldsmith and Warhol, and there is no evidence that Warhol believed he needed a license to do what many artists do when they take up a particular subject or theme: develop a series. In this case, Warhol’s focus on Prince resulted in 12 silkscreen paintings, two screenprints on paper, and two drawings (the “Prince Series”). And this is where things start to get a little contentious. Some interpret Goldsmith as arguing that Warhol had no right to make more “Princes” unless she was compensated.

Not long after Warhol’s Purple Prince appeared in Vanity Fair, Warhol died, and his remaining artworks and the copyrights were left to the Foundation. After Prince’s death almost a decade later, Condé Nast wanted to use Warhol’s “Prince” again, on the cover of a 2016 tribute magazine. They ended up licensing a different version from the series: Orange Prince.

Goldsmith then contacted the Foundation to discuss the issue and, feeling confident in its position, the Warhol Foundation filed for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement. Goldsmith countersued the foundation for copyright infringement—but interestingly, did not sue Condé Nast or Vanity Fair.

Lynn Goldsmith’s photo of Prince and the Andy Warhol artwork derived from it.

With all of the arguments from the many friends of the court, it is important to remember how the Supreme Court itself identified the question presented in this case when it agreed to hear it: “Whether a work of art is ‘transformative’ when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material (as this Court, the Ninth Circuit, and other courts of appeals have held) or whether a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of the accused work where it ‘recognizably deriv[es] from’ its source material (as the Second Circuit has held).” In other words, for a work of art to be considered transformative, is it more important that it have a different meaning from its source material, or that the source material cannot be recognized?

Against this backdrop, the SG takes the position that the foundation’s licensing of a different Warhol artwork from the Prince series for a magazine cover was not fair use. But it ignores far bigger questions. Goldsmith’s claims against the foundation were clearly centered on the question of Warhol’s creation of the entire series of artworks, bearing down on the interplay of copyright protections with First Amendment concerns. But the SG does not examine Goldsmith’s broader allegations that the entire “Prince Series” infringes her photograph, or her demands for relief—except to say that Warhol’s fine art uses are likely not infringing on Goldsmith’s copyright.

Why would the SG say its brief is filed in support of Goldsmith, while doing so in a manner so narrow that Warhol’s series of artworks depicting Prince would likely be found a fair use?

For now, we simply don’t know the reason for the SG’s position. What we do know is this:

- The SG’s brief rightfully emphasizes that copyright law does two things: it encourages both the creation and dissemination of creative works “while preserving breathing room for secondary uses.” Both original and secondary works must be protected in order to uphold the Copyright Law’s goal of promoting “innovation.” Fair use is just one of the ways the Copyright Act seeks to achieve this balance.

- Fair use analysis requires application of the entire four-factor test established in Section 107 of the Copyright Act, and analysis should focus on a “particular use” that is alleged to infringe.

- Yet the focus of the SG’s brief is just the first prong of the four-part analysis: the purpose and character of the use. The “particular use” identified by the SG is only the foundation’s licensing of the Orange Prince image to Conde Nast. The SG thus asks the Supreme Court to leave aside for now the larger question underlying the legitimacy of Warhol’s entire series. This leaves unaddressed the question of why Condé Nast selected Warhol’s “Prince” over the many available Prince images, including Goldsmith’s.

Something important is missing from the SG’s brief and, frankly, from other briefs in this case: meaningful discussion of the relevant market in which the impact of the choice of Warhol’s image over Goldsmith’s should be measured. The SG assumes that because the Warhol Foundation was able to license Orange Prince to Condé Nast, that the market is “images of Prince,” and asserts essentially that Warhol unfairly competed and in fact supplanted Goldsmith’s ability to license her own image of Prince—as if, but for the existence of the Warhol image, Condé Nast would have licensed from Goldsmith directly.

Let’s assume that is true. This means that there are only two images in this market: Goldsmith’s and Warhol’s. Yet that Condé Nast specifically wanted a work by Warhol speaks volumes.

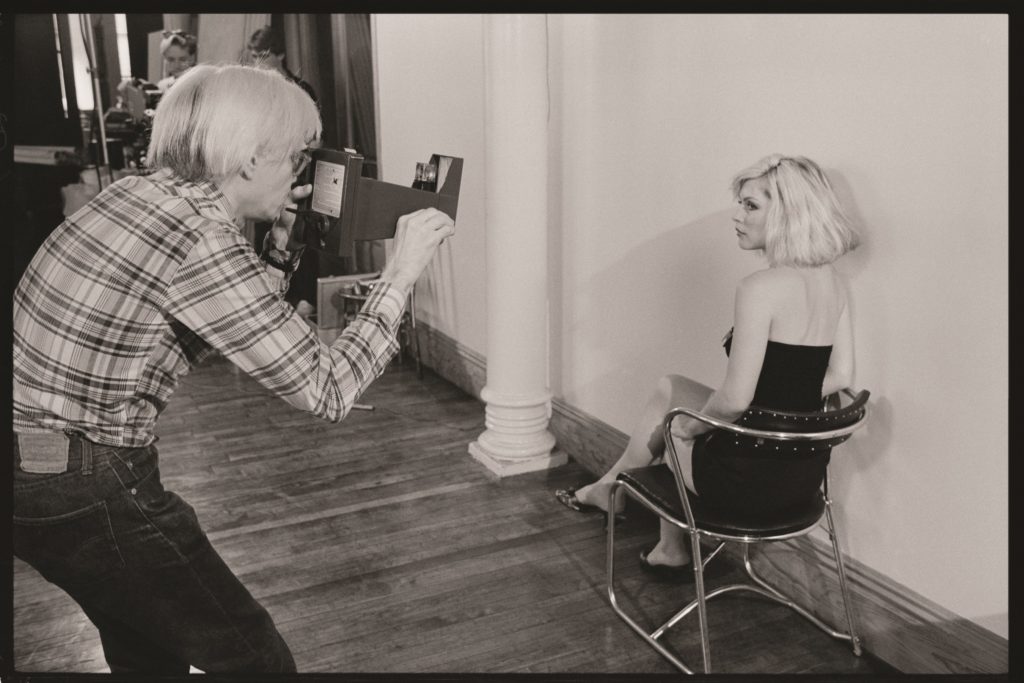

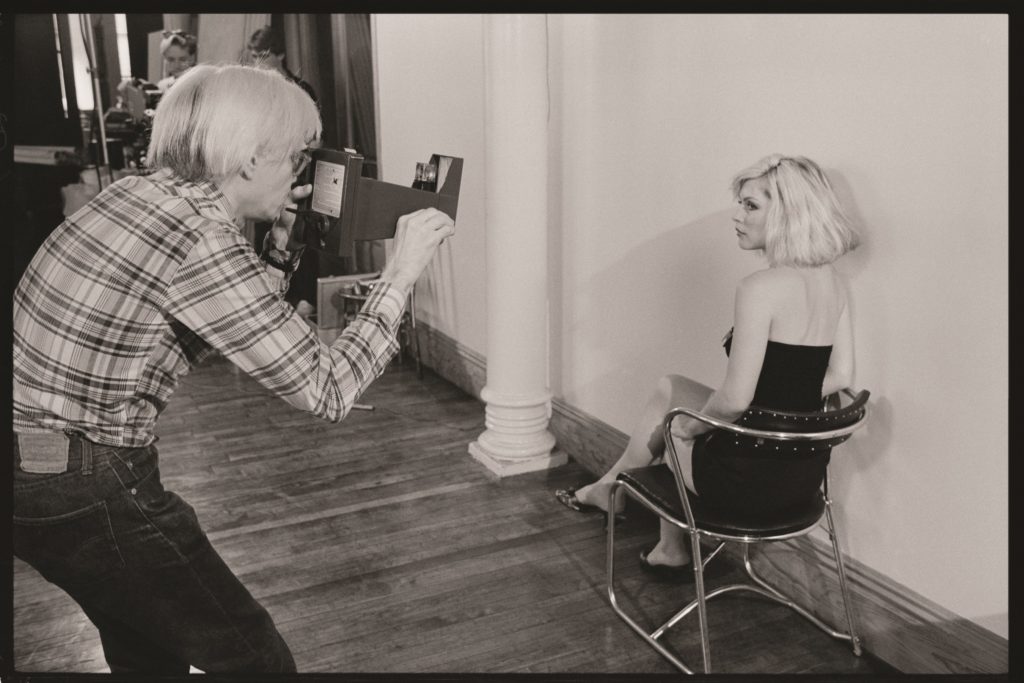

Debbie Harry and Andy Warhol. Photo: Chris Stein.

In addition, the record does not address whether available licenses offer any option suited to permanently existing artworks. It is assumed by many that a license for use in a work of fine art would even be available, and such is not the case. For example, Getty offers licenses, but by their express terms any such license may also be revoked by Getty after the fact, at any time for any reason that it chooses, and may require immediate destruction of the use. For works of fine art expressed in a physical medium, this would make destruction of artwork a matter of contract rather than of the combined interplay between Copyright Act fair use and the First Amendment. This framework is existentially inconsistent with using licensed material in works of fine art that may be sold to museums or collectors.

In its final written reply before oral argument, the Warhol Foundation attempts to bring the Supreme Court’s focus back onto transformativeness as a settled element of fair use analysis and jurisprudence.

Nobody has argued that Warhol’s works were not transformative. Rather, Goldsmith’s supporters argue that it doesn’t matter if he did transform it—the foundation shouldn’t be able to license any of Warhol’s “Prince” artworks in competition with Goldsmith’s photograph.

Regardless of who one may favor or what one feels is essential to highlight in this case, one thing absolutely NOT at question is whether copyright law protects photographs as an art. Of course it does; nobody seriously argues otherwise. And via fair use, copyright law also protects further creation using pre-existing copyrighted material in ways that are critical to our free-thinking society. Our laws have historically balanced the recognition of protectable, enforceable copyrights with the right to use copyrighted material for other socially valuable reasons, such as creative expression.

If the Supreme Court takes the position urged by the SG, to focus only on commercial licensing of Warhol’s Prince, what will happen? The Court could say simply that, as the SG urges, there is no “categorical rule protect[ing] all appropriation art (or visual art more generally)“ and send the case back to the lower courts for a full hearing on the merits after further development of the record. The SG also refers to the “underdeveloped record” below, meaning that the SG thinks that facts important for a nuanced fair use analysis are missing. The implication is that a fuller development of the record, and the careful application of that more developed fact record to analysis under the four-factor test for fair use, could well go against Goldsmith.

Supporters of both photographers and of artists whose work employs appropriation are in favor of practical, meaningful, and sensitive application of the Copyright Clause in the U.S. Constitution, the First Amendment, and Section 107 of the Copyright Act. We will simply have to wait and see how it all plays out. For those who are interested, on the afternoon of October 12, the date of oral argument in the case, the Supreme Court’s website will post transcripts on its web site, and on the Friday of that week, the official audio recording of arguments will also be made available.

Amy Goldrich is an attorney whose practice focuses on the representation of artists working in all media, including artists who joined in the filing of an amicus brief in Andy Warhol Foundation, Inc. v. Goldsmith. She holds an LL.M. in Trade Regulation from New York University.