Meet Amy Ernst, Who Has Quietly Been Making Dazzling Collages and Prints for Decades

Katie White

Amy Ernst doesn’t shy away from the fact that she is the granddaughter of the hyper-famous Surrealist artist Max Ernst, and the daughter of Jimmy Ernst, the Abstract Expressionist. (Her grandfather, too, she’ll let you know, was a portrait painter.)

Earlier this fall, Ernst had a solo exhibition at Die Galerie in Frankfurt that coincided with “Surrealism and Beyond,” an exhibition of work by her grandfather and father, along with Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, and Roberto Matta.

But as a collage and print artist herself, Amy Ernst has a wealth of knowledge and interests all her own. We recently sat down with Ernst, who shows with New York’s Gallery of Surrealism to talk about her favorite bygone art supply store, her love of Flemish painting, and how a fascinating family member you probably know nothing about is inspiring her latest creations.

Portrait of Amy Ernst, 2019.

Coming from the family you come from, did you always know you were going to be an artist?

I didn’t start out being an artist, nor did I want to be one. I was interested in the theater. I started working in the theater at 14, doing the grunt work, behind the scenes. I started with the Straw Hat Festival in East Hampton at the John Drew Theater under the guidance of Edward Albee, and then with the Yale Repertory Theatre. I knew that place well. My mother went to Yale for graduate school back in the 1940s. I grew up with these people around me, like the actress Maureen Stapleton. I thought I was running away from being an artist. Later on, I realized that it chose me.

Your father, Jimmy Ernst, he didn’t encourage you to make work?

No. He told me, “Don’t marry an artist. Don’t be an artist.” And ta-da! I also married an opera singer, which didn’t go very well. But nevertheless, when I’d come home and draw and he’d see me and just say, “Loosen up, loosen up, you know?” Then he’d put out a big piece of paper for me so I could draw something big. He’d say “Bigger! Bigger!” I’d be worried about drawing on his table but he didn’t care. My father, I wasn’t allowed in his studio when he was working. Still, sometimes I would go in. I would knock on the door and ask if it was okay. My grandfather, on the other hand, nobody was allowed in the studio when he was working. I only visited him at his studio a few times as an adult.

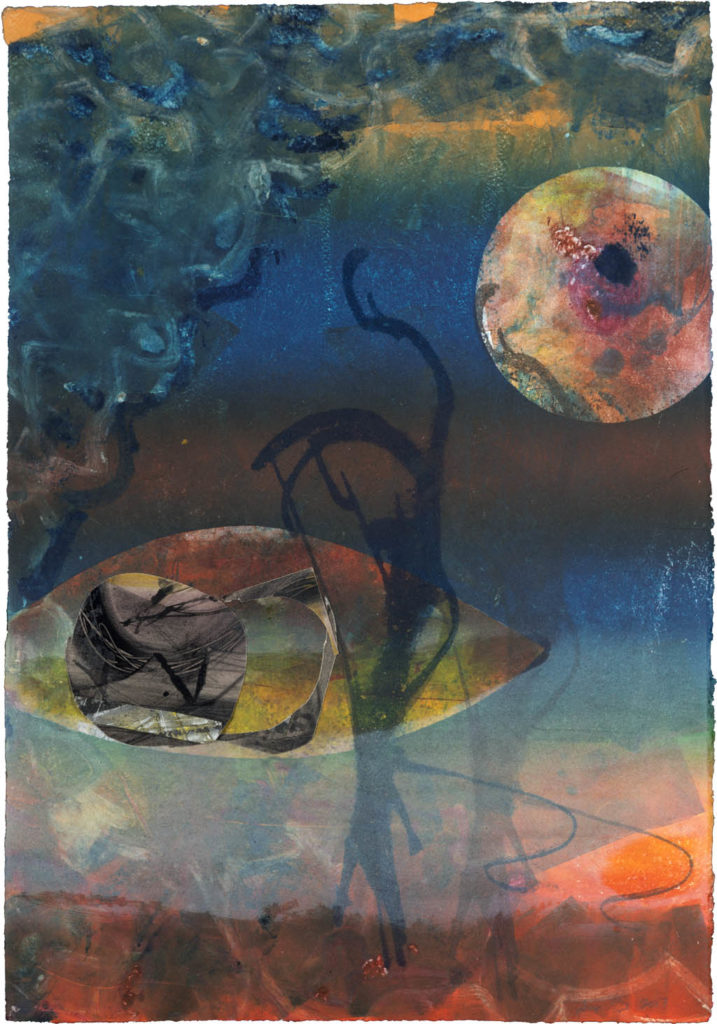

Amy Ernst, Sea Urchin in Flight (2017). Courtesy of Gallery of Surrealism.

How did you start making artwork then?

Well, I’d always had the stage sets. Then I went to Indiana University to get my Master’s in Arts Administration and Business after reading Lee Seldes’s book The Legacy of Mark Rothko, about how his estate was sold out from his daughter, and I decided that nobody’s going to do this to my family. I came back to New York in ‘84, and I was making these stage sets, little set designs in collage form. Most of those were sadly lost or destroyed. My father had recently passed away, and my marriage wasn’t working out, so perhaps it was out of loneliness that I started branching out, taking classes at the Art Students League. I’d also started to have trouble with my eyes, macular dystrophy. At night I can see very well without my glasses, like a cat, but it can be hard to see in the daylight, which influenced the way I chose things. The colors got brighter, the images more abstracted. I tend to use similar forms like ovals and circles that I’d cut out of tracing paper and make certain dyes and cuts when I’m doing my printmaking. When I was painting, if I didn’t like something, I would just cut right into the canvas, which I’m very sorry about with some of the pieces that I deconstructed because they could have become something else.

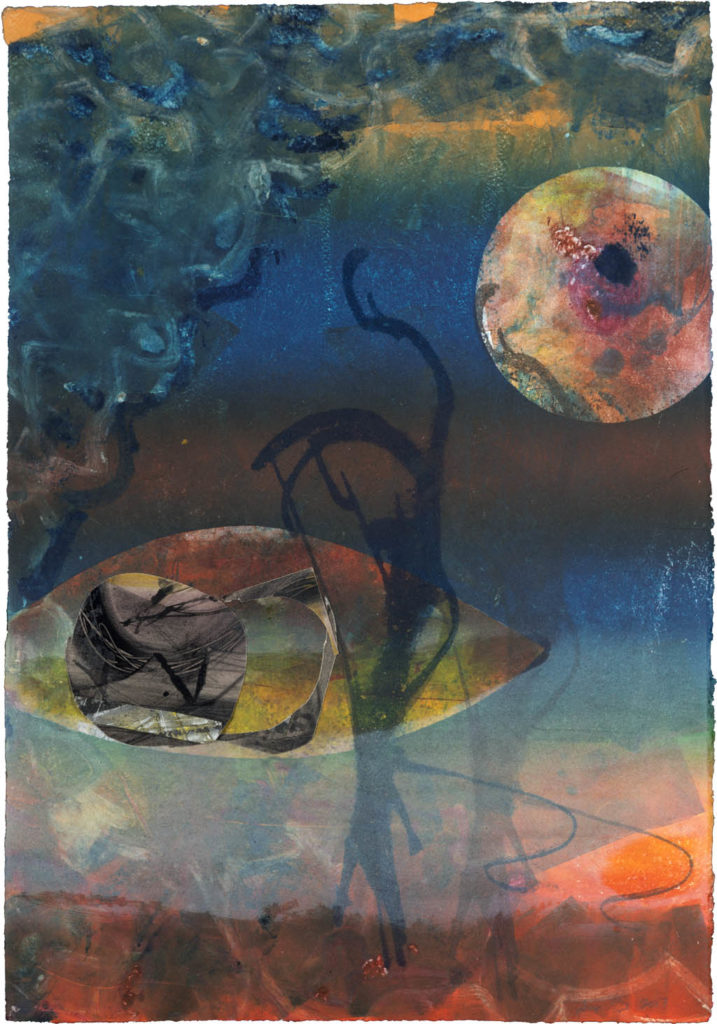

Amy Ernst, Within the Ancient Walls (Blue Clouds Over Ancient Walls) (2014). Courtesy of Gallery of Surrealism.

You mentioned to me that your grandmother, your father’s mother, Louise Straus, the first wife of Max Ernst, has had a particular influence on your life, though you never met her?

Yes. I went to Manosque, in France, where my father’s mother hid out during the war. I never met her but my father always told me I was very much like her. She was an art historian and a curator who got her doctorate in art history, at the University of Bonn. By the war years, she and my father had already been separated. He had gotten a job typesetting at a publishing and eventually made it to New York. She was Jewish and being hidden by the writer Jean Giono, who maybe didn’t do such a good job. She was translating Giono’s writings from French into German. He was supposed to be helping her get her papers in Marseille. She was ultimately captured by the Vichy and was one of the last people killed at Auschwitz. Giano’s daughter, who’s in her late 80s or 90s now, I met her and she told me, through translation, that I looked like Lou.

At the back of the house there, there was a swing attached to a tree and I went out and introduced myself to the spirit of my grandmother and told her I was sorry we’ve never been able to meet. My life since that trip has kind of been about acknowledging her. There’s a book in German about her life called Notre Dame de Dada by Eva Weissweiler I’ve been wanting to have translated. In recent years I’ve also been finding old photographs from my mother’s side of the family, of people I don’t know, from the 1880s and 1890s. I want to find images of these women in black and babies in long dresses and incorporate them into my works.

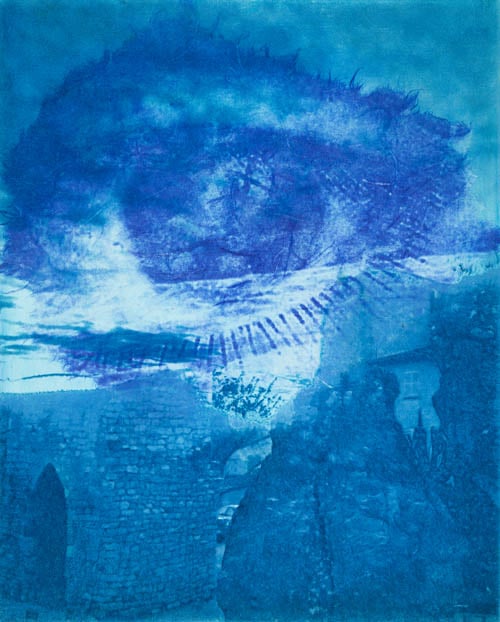

Amy Ernst, The Madness Within Itself (2016). Courtesy of Gallery of Surrealism.

Have you always worked in collage and print?

For a while I was working in encaustic and was taking classes at the Met, looking at all these Medieval paintings. Encaustic is very dangerous, because of the solvents. You could blow yourself up. But I learned how to make fish-eye glue. I’d get the fish eyes from New York Central Supply which had everything. You’d see the little eyes looking out at you. My father used to shop there as well, my grandfather too. I also incorporate things I find in nature, sticks of wood that I scan and incorporate in my work.

Am I right to think you work intuitively?

I try to, let’s put it that way. I try not to be influenced by the work around me. It’s very, very hard, of course. One thing my father always told me, when you start a new project, take everything down. So you’re thinking only about the work at hand. Don’t be influenced by color or dimension or anything like that. I try to follow that. I tend to work in series, though. I live in Florida now, but when I’m in New York, I work in the studio of my friend, the print artist Lisa Mackie. Oftentimes I go into the studio thinking I’m going to make one thing and it turns out entirely differently.

Amy Ernst, Dream Catcher (2017). Courtesy of Gallery of Surrealism.

Who do you see as your influences?

Not one artist, necessarily, but more eras or styles. In the late ’80s and ’90s, I was incorporating Medieval and Renaissance images into collages of what I called Renaissance Surrealism. The Netherlandish painting Petrus Christus was my favorite. I also tend to cut up wallpaper books and magazines. Friends would say, “Don’t come near my library!” Somewhere in the cabinet of the mind where the gets rusted and stuck, I’ve filed away images I’ve seen at museums, the Met. I’ve always loved Flemish work, and Medieval and Renaissance too.

Why do you think that is?

The hands and the eyes in those paintings. I never try to think too much about why I like it or what it means because it puts too much pressure and closes up the work. I try not to become too attached. I want people to be able to see it in their own way. These works take a lifetime and a moment. The works I like might even be the most successful. I tend to work on multiple things at a time, and just tape works and leave it for awhile so I can come back.

How do you know when a work is done then?

When you ask that question. That’s what my father said to his students at Brooklyn college. It’s better to stop then to go too far. Sometimes I deconstruct a work and make it into something else, though, just like we do with our lives.