The Self-Taught American Painter Horace Pippin Has Long Been Overlooked by Museums and the Market. Here’s Why That Should Change

Katie Rothstein

Artist Stories brings to light the careers of artists whose life stories and work may not be part of a traditional art history education. In this series, we’re sharing stories from art history as a first step to building a more diverse canon.

Horace Pippin was the first African American artist to be the subject of a monograph and, during his life, was featured in both commercial and museum exhibitions around the country, At the time of his death, in 1946, the New York Times noted that Albert C. Barnes, founder of the Barnes Foundation, described Pippin as the most important Black painter in America. And yet, in the years since, his name has faded into relative obscurity.

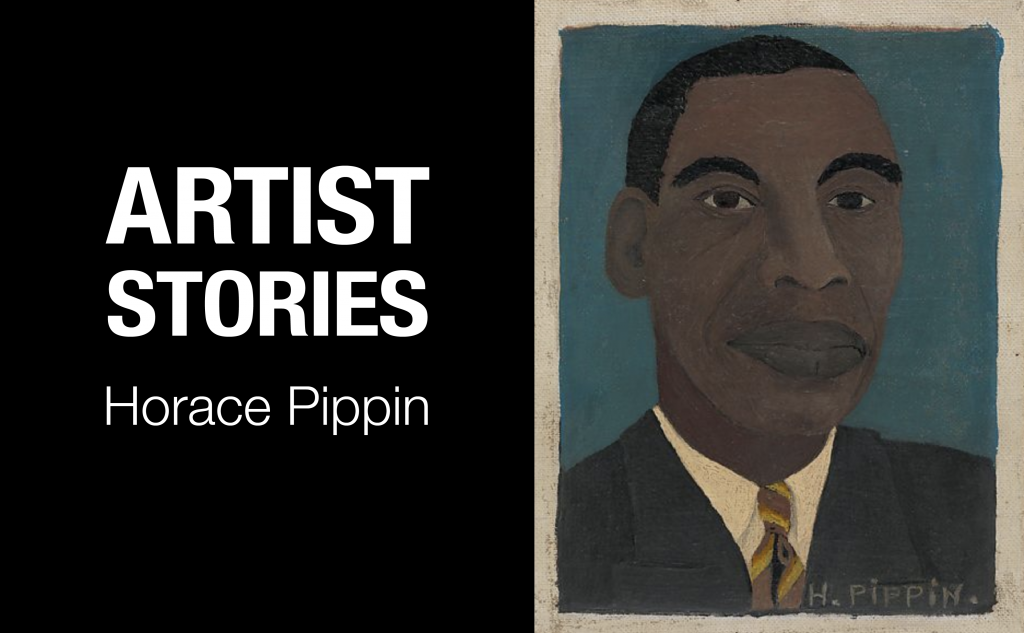

Horace Pippin, Harmonizing (1944).

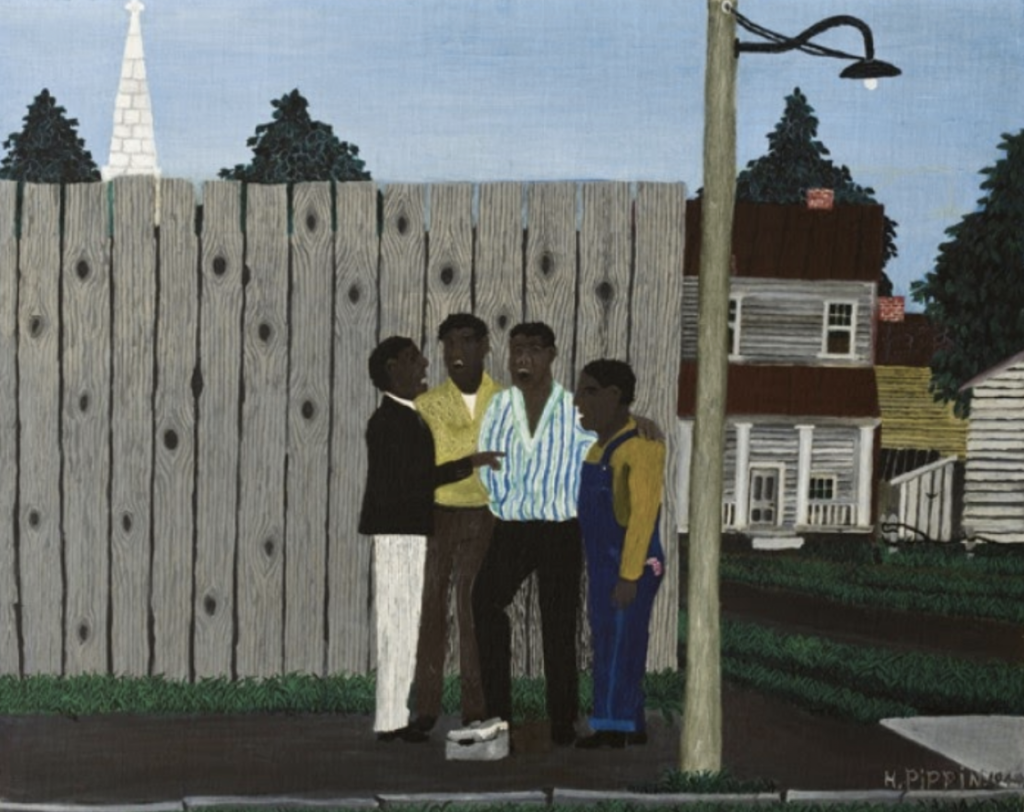

Born February 22, 1888, Pippin was a direct descendant of enslaved peoples and a World War I veteran. While serving with the all-Black 369th Infantry, also known as the Harlem Hellfighters, Pippin was wounded by a German sniper. He lost mobility in his right arm and never completely regained it. When he returned from the war, Pippin began making art in part as a form of physical therapy. He taught himself to paint by holding the brush in his right hand and using his left arm to move it.

After completing his first oil painting in 1931, Pippin went on to complete some 140 canvases between then and his death, 15 years later. Some of Pippin’s paintings depicted scenes from the war, as well as the racism he encountered upon his return to the US. Others are history paintings, biblical scenes, or simply show Black people in everyday life.

Mr. Prejudice (1943) shows soldiers fighting both the war abroad and the war against racism at home.

Compared to contemporaries such as Jacob Lawrence, who has enjoyed continued scholarly and institutional attention, and whose influence can be felt in the work of contemporary artists such as Nina Chanel Abney, Sanford Biggers, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and Kerry James Marshall, Pippin has been largely overlooked.

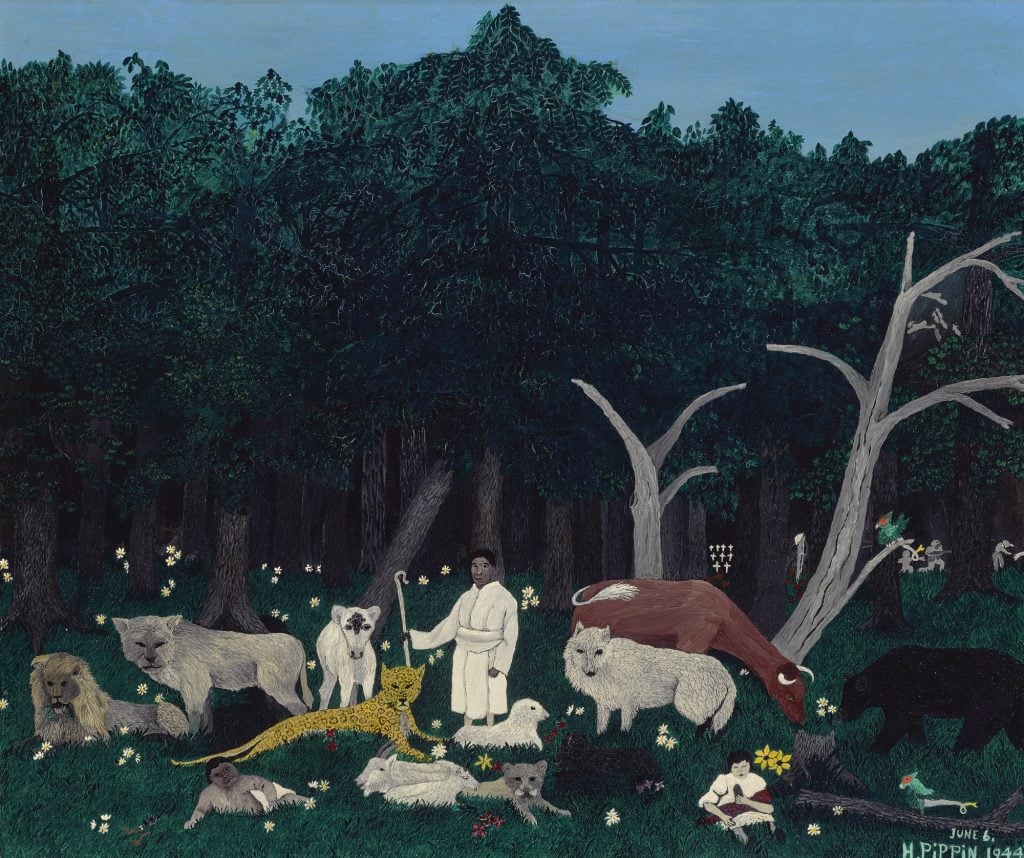

While Pippin’s auction record stands at more than $3 million for Holy Mountain I (1944), his next highest result is just $385,000, which was paid for that same painting when it was sold 30 years earlier in 1987, according to the Artnet Price Database. What’s more, his work has only come to auction 20 times since 1986. (Lawrence, by contrast, has had work come to auction 605 times, and his record is nearly double Pippin’s.)

Part of the lack of auction momentum for Pippin’s work almost certainly has to do with a dearth of support from institutions, which have long overlooked artists of color. Since 2013, Pippin has had only one solo exhibition, at the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Pennsylvania.

Holy Mountain I (1944) sold for over $3 million at Sotheby’s in 2018.

Another reason that Pippin remains relatively unknown in the mainstream art world likely has to do with lacking the particular narratives about education, influence, and lineage that art history tends to value. Pippin was self-taught, disabled, and a veteran. (Lawrence, on the other hand, was educated, married, and became a teacher himself.)

Whose stories are told? Whose are valued? Despite being one of the most important artists of his time—and his influence on contemporary painting remains clear—Pippin has received little recognition. It’s time to surface his story.

Interested in learning more about the artists you love? Sign up for Artist Alerts to receive free customized email updates about all your favorite artists.