‘Art Can Offer Respite’: Italian Old Master Dealer Carlo Orsi on Why a Slower Approach to Collecting Is Right for Uncertain Times

Artnet Gallery Network

Sometimes the best response to a crisis is the measured and mindful approach — at least that’s the ethos adopted by London’s Trinity Fine Art, a leading purveyor of Old Master works since 1984. In the past months, whilst the art world has scrambled to launch digital viewing rooms, online fairs, zoom talks, and countless newsletters, Trinity has taken a zen master approach to sales, aiming to deepen and cultivate relationships offline.

Recently, Carlo Orsi, a dealer of Italian antiquities and the owner of Trinity Fine Art, spoke with Artnet News about why the “slow art” approach is an ideal one for our unusual age.

The world has changed dramatically in recent months. Can you explain any shifts the gallery has and hasn’t made to adjust?

At our core, we haven’t changed at all. We have avoided the race to do everything online—the virtual viewing rooms, the multiple newsletters. Our core business is based on a series of carefully nurtured, one-to-one relationships, which is a perfect business model for the current times.

Naturally, the externals have temporarily been modified and curtailed and we had to cancel travel plans and fairs and restrict access to the gallery, but we are, and always have been, a boutique gallery with a tailor-made approach that doesn’t rely on foot traffic, or a frenetic program of fairs and exhibitions. Before the current health crisis, the art world literally could not stop moving around and the shock of this unforeseen halt has led us to concentrate much more on interpersonal relationships and the immediate spaces in which we live.

You’ve mentioned that your gallery subscribes to the ethos of “slow art” with a focus on looking deeply at individual works rather than many works. How did the gallery arrive at this outlook?

The gallery’s approach is the result of my own personal ethos in this regard, which I have been refining and developing for over 20 years and is guided by a single imperative force: quality above all else.

When I started working as a dealer in the 1980s the pace was frenetic and quality was not my credo. As a proud son of my generation, I always wanted more and was in a hurry to get it, buying everything I could lay my hands on and selling it swiftly for small profits. The important thing was to always keep moving, to learn, and grow.

Since then, the pace of work has only increased with the exponential growth of mega-galleries in the 1990s and the globalization of the market, a phenomenon which we are still living through today. But that marked a turning point for me and my career, as I decided to give up the module of old-school, fast-paced generalized art dealing to instead specialize purely in Old Master paintings and sculpture, preferably Italian, and with that to exhibit only a few pieces, which sometimes were not even for sale.

In doing this, I purposefully distanced myself from the purely commercial “hamster wheel” aspect of the business, allowing more space and time for research. It was a counterintuitive choice in the 1990s, but now it can clearly be seen as an alternative to a globalized, increasingly homogeneous art market.

Carlo Orsi of Trinity Fine Art.

What is the experience you want collectors to have with the artworks you’re showing?

We want to encourage people to stop and really look—to go beyond the name of the artist and appreciate the object for both its craftsmanship and historical and cultural significance. We want to share our knowledge with our clients by way of the in-depth, scholarly catalogues since the acquisition of knowledge is a wonderful opportunity to enrich and broaden horizons.

Sure, my career was made by big discoveries and blockbuster names—Pontormo, Canova, Bronzino, Botticelli—but aside from those big hits we make a point of offering high-quality pieces by lesser-known artists. We want collectors to be reminded of what is—or should be—at the core of our trade: art, culture, extraordinary minds, and significant moments in time.

Do you think people will be more eager to fill their homes with art after the experiences of quarantine?

I don’t think that the experience of quarantine will necessarily lead to the acquisition of more artwork in terms of quantity. However, I feel that acquisitions will be more mindful and calculated, with more thought and research put into the process. The densely packed calendar of auctions and fairs of the past decade has dictated the timing of collecting, accelerating acquisitions sometimes at the expense of quality, and emptying the experience of communion with works of art.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Les Deux Majestés (The Two Majesties). Courtesy of Trinity Fine Art.

How has the gallery connected with, or tried to connect with, clients in a way that is slower-paced or more intimate?

In our effort to redefine and slow down the way we interact with art, we’ve been focusing on experience rather than goods. During the last decade, social economists have been suggesting that because of the rise of the digitization, people are left hungry for real, in-person, physical experiences.

Museums, just like brands, have been pouring money into this, trying to tighten their connections to their audiences and create compelling experiences that genuinely attract and hold their attention. We too have been focusing on creating something that can be felt, rather than just purchased or passively observed.

What’s an example of how the gallery has worked to establish these more intimate relationships between collectors and artworks?

For instance, we’ve held several small, private events in Italian museums, during which small groups of clients had the place all to themselves, to roam the rooms freely, experience the collection in its entirety, and to pause and contemplate particular works that grabbed their attention and “spoke” to them. The experience allowed them to draw cultural and artistic connections with their own collections and come out enriched and energized by their visit. Simply put: The time and space allowed them to renew their passion and commitment to art.

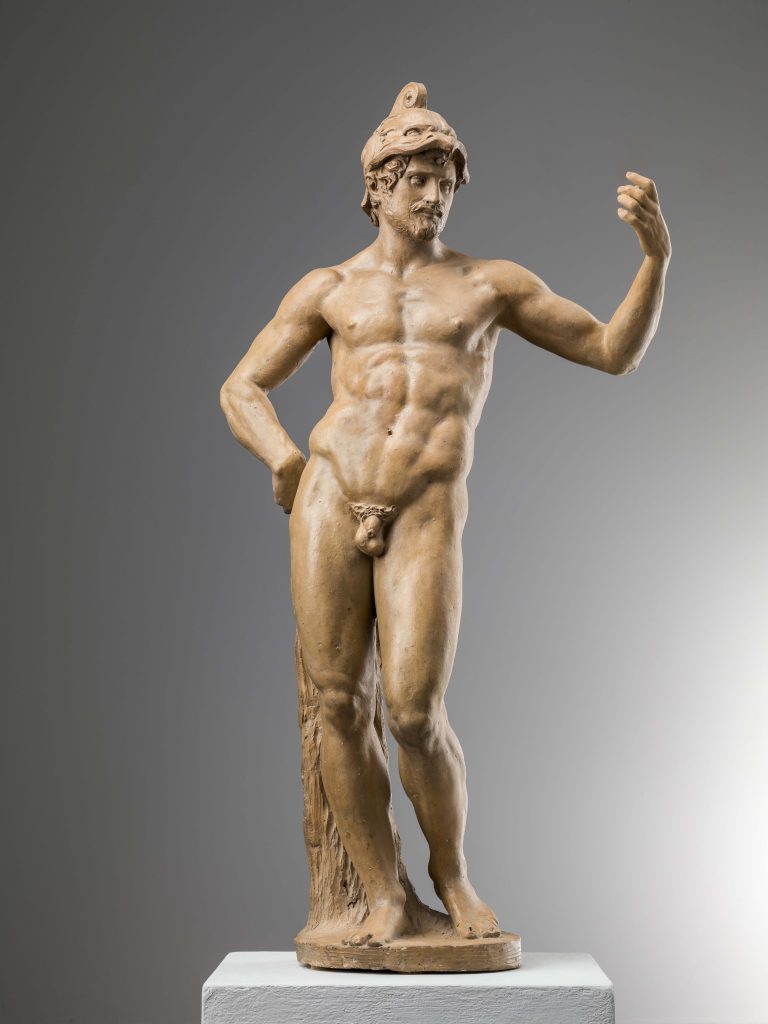

Stoldo Lorenzi, Mars (1565–1575). Courtesy of Trinity Fine Art.

Do you think that the more deliberate, slower pace will last in the future?

I would hope that the art trade could slow down, yes, but I don’t see it happening tomorrow. However, it must be recognized that the current market model has been pushed to its natural limit and that, lately, we are hearing new voices and ideas which propose the concept of art as a mindfulness practice, or the benefits of mindfulness-based art therapy.

It seems clear to me that as a community we are rediscovering the transformative value of art. In this current global crisis, we may be feeling anxious and adrift, and although I would not go as far as to suggest that simply looking at art could be a form of mindfulness, I am confident in saying that in difficult times, art can offer respite, answers, and a safe harbor amid the chaos.

Agnolo Bronzino, Madonna & Child with the infant St John the Baptist. Courtesy of Trinity Fine Art.

What’s one way that close, studied observation of artwork has had consequences for your career?

A good example would be my first big discovery: a small panel of uncertain attribution that I bought trusting my own instinct in the 1990s and which, 20 years later, would be finally accepted as a lost work by one of the most talented proponents of Florentine Mannerism, Agnolo Bronzino. A little-known piece with a dubious attribution, it was referred to me by a scholar, Philippe Costamagna (who recently published a book on connoisseurship). We both knew it existed from a black-and-white photograph, but it took a while to be able to see it first hand.

Once I made contact with the owner and saw the painting, I immediately bought it and that then started a series of consultations with art historians and museum curators to confirm the attribution. Finally, the piece was recognized as being by Bronzino and was subsequently sold to a prominent private collector. To undertake all this at the beginning of the 1990s was not by any means the obvious route, especially in Italy, where the art market was very much focused on interior decoration. In this case, I put aside the commercial aspect of the business, focused on the research, and in doing so discovered a masterpiece.