The 85-Year-Old Artist Marc Vaux Has a System for Making Decisions in the Studio—and It Might Help You, Too

Artnet Gallery Network

“Art is a business of making decisions,” says Marc Vaux, an octogenarian artist whose wall sculptures are now on view in “The Edge and Beyond” at Bernard Jacobson Gallery in London. “For me, there are only three ways of reaching a decision: randomly, rationally, or intuitively.”

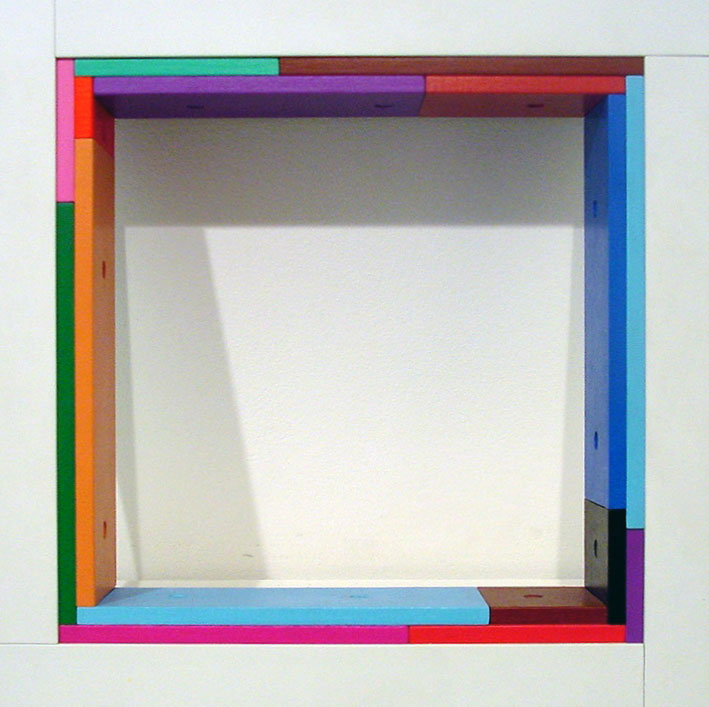

All three aspects of decision-making are manifest in each of Vaux’s works. Take, for example, his wall relief SQ 0/3 (1992), which features a square aluminum structure lined on the inside with overlapping layers of painted MDF—four on each side. The size and distribution of the colored pieces are random, determined by a computer program. The structure of the piece, a simple square, is the rational part. Finally, the colors are intuitive, chosen in the moment by the artist.

Marc Vaux, SQ 0/3 (1992). Cellulose on aluminium and acrylic on MDF, 10 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 2 in. Courtesy Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

For him, in fact, color is always the intuitive part, and he has strong theories about the ways in which it operates on an emotional and physiological level. “Color is known to have a direct effect upon the central nervous system, arguably the most effective modifiers of human response, over sound and touch,” the artist said in a monograph of his work from 2011. “I see no reason why color can’t be equated with melody and be as memorable.”

Born in 1932 in Swindon, England, Vaux first came to prominence in the early ’60s when his work was included in “Situation,” an exhibition at the Royal Society of British Artists, which brought together a group artist peers, such as Robyn Denny, William Turnbull, and John Hoyland, who made large, abstract paintings in response to the Abstract Expressionism movement happening across the pond. Not long after that, though, Vaux’s work diverged from that of his contemporaries as he honed in on mostly formal concerns, and began making sculptures and more experimental wall-hanging works.

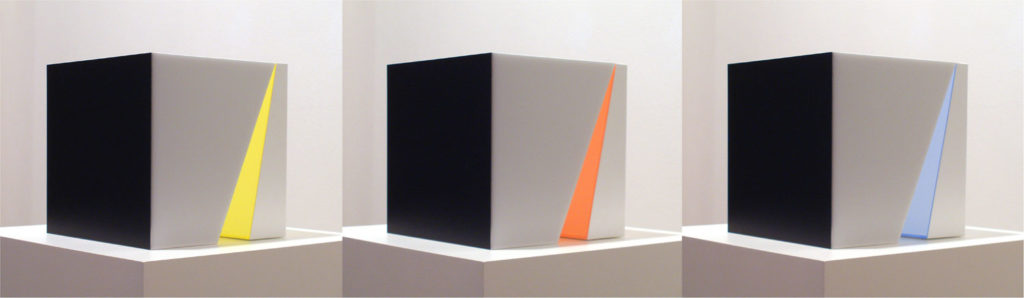

Marc Vaux, Light Cube (2006). Acrylic, 8.46 x 8.46 x 8.5 in. Courtesy Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

Since then his work has been shown around the world, and is now included in major collections throughout Europe, such as those of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Gallery, and the Museum of Modern Art, Belgrade. Vaux turns 85 this month, and still works in his London studio every day, continuing to fine-tune the methods he and ideas that have defined his art.

Throughout the majority of his career, Vaux has focused on four-sided shapes, both in terms of form (square canvases and what he terms “wall constructions”) and content (painted square shapes in the vein of Rothko or Albers, for instance). However, within the last five years, Vaux has abandoned four-sided forms almost entirely, choosing to work now on ovular structures.

It came about as an attempt to eliminate horizontal and vertical lines in his compositions, formal elements that have dominated visual art—especially painting—since its inception. For him, it’s also a metaphor for our place in the universe, physically and metaphysically. “We live on a planet that goes around the sun in an orbit, while light travels in straight lines,” he says. “We’re talking about pure space here. In outer space, there is no vertical or horizontal.”

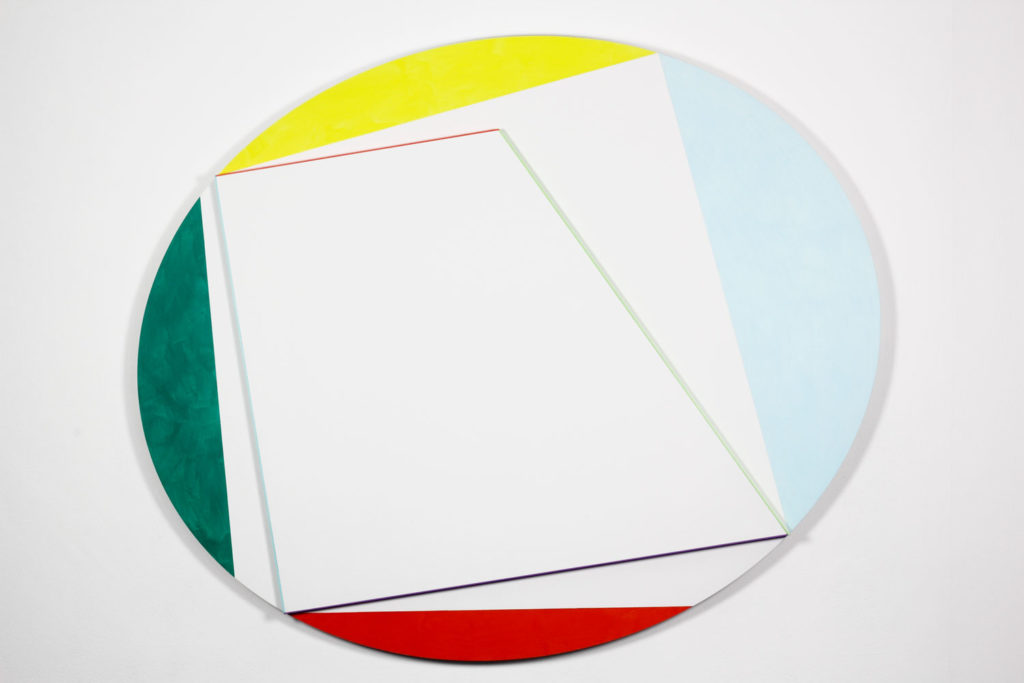

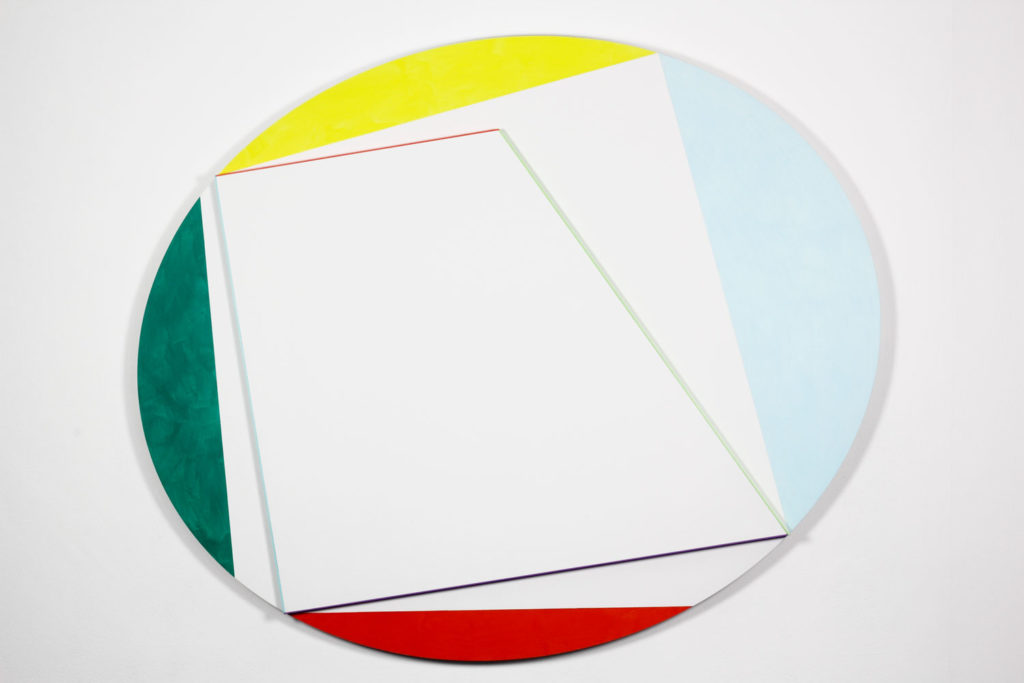

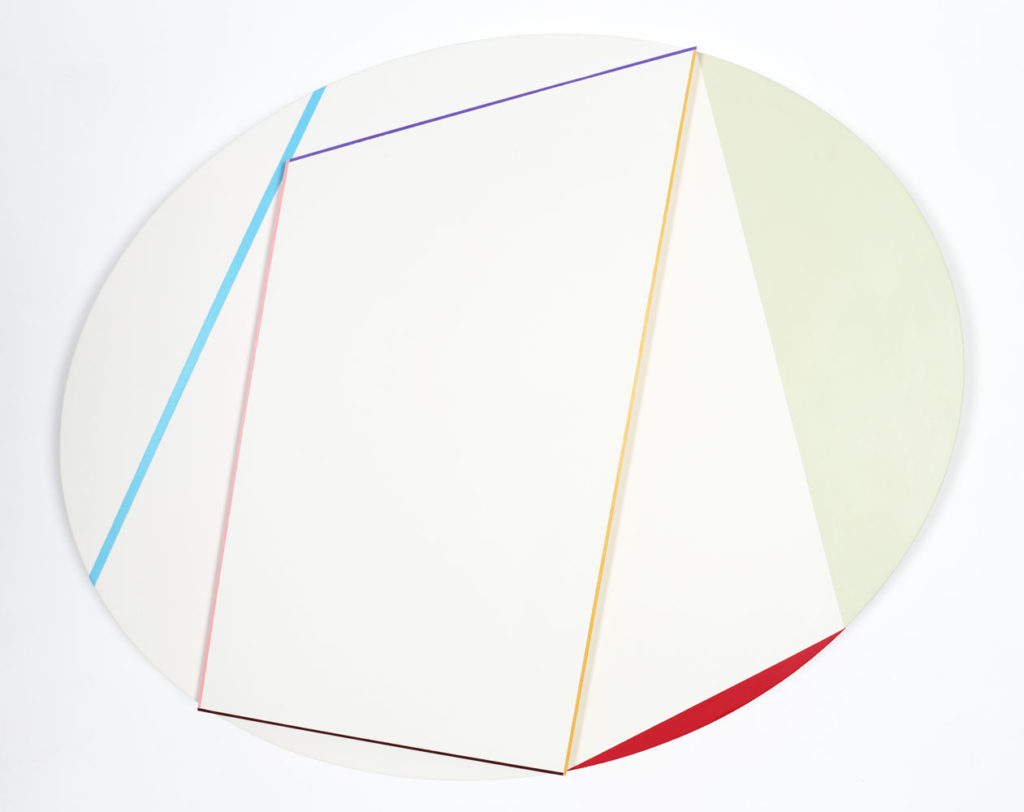

Marc Vaux, OVS.17 (2017). Acrylic on MDF, 15 3/4 x 19 3/4 x 1 5/8 in. Courtesy Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

It’s also about accepting the chaos of the world, and creating ways to work within it. For example, look at one of his new works, such as OVS.17 from this year. The main structure—the rational part of the composition—is an oval, and once again the colors represent the intuitive aspect. However, the colors never touch each other—they are divided by large, white shapes, the angles of which are determined randomly.

“My colors are hardly ever edge-to-edge these days,” he says. “I’m trying to avoid that as much as possible, because the minute you put colors edge-to-edge, and they are absolutely next to each other, they interact.” If you can figure out a way to use multiple colors in a work without falling into that trap, he says, “then you’re onto something.” An analogy occurs to Vaux. “I tend to think of color in the way that a cartographer would when making a map,” he says, “It defines an area.”