Reviews

Kevin McGarry On the Future of Art Criticism According to Jason Farago

It’s a bold move to do a print journal in 2015, to say the least.

Photo via evenmagazine.com. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town.

It’s a bold move to do a print journal in 2015, to say the least.

Kevin McGarry

There’s a new art magazine in town, and that’s not a euphemism for blog.

During Frieze New York, Guardian contributor Jason Farago launched a print journal. Even—named after the titular punctum of Duchamp’s masterpiece The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even—will come out three-times-a-year and is proportioned much like a finger-width paperback. At this size, it’s a pleasure to page through and carry. The antithesis of another fashion-cum-art-cum-lifestyle reader, the design is in the service of text, with images placed throughout as visual footnotes.

In his manifesto prefacing issue number one, Farago tells a tale of two art worlds: the market art world of galleries and superficial bridges to popular culture (like social media) and the discursive art world of scholarly essays and symposia. This he casts as one of several parallel dichotomies holding art discourse in limbo these days:

How can we account, then, for the pervasive sense that contemporary art is not moving forward, is spinning its wheels? At a time of unprecedented attention for visual art, not to mention a perpetual market boom, why the endless nostalgia?…. Either we ask art to do things it cannot do, making fantastical claims about subverting authority or rewiring society, despite decades of evidence that art has no such power. Or else we fail to notice all the things art actually can do, and reduce it to the selfie backdrop of the day…. Even is a new effort to refashion the dominant discourse, to figure out just what art can do.

It’s a lofty goal, but an honest one. Perhaps a more difficult promise to institutionalize is that Even will be a publication where, essentially, people stop being polite and start getting real.

Cover of Even magazine. Photo courtesy of Even.

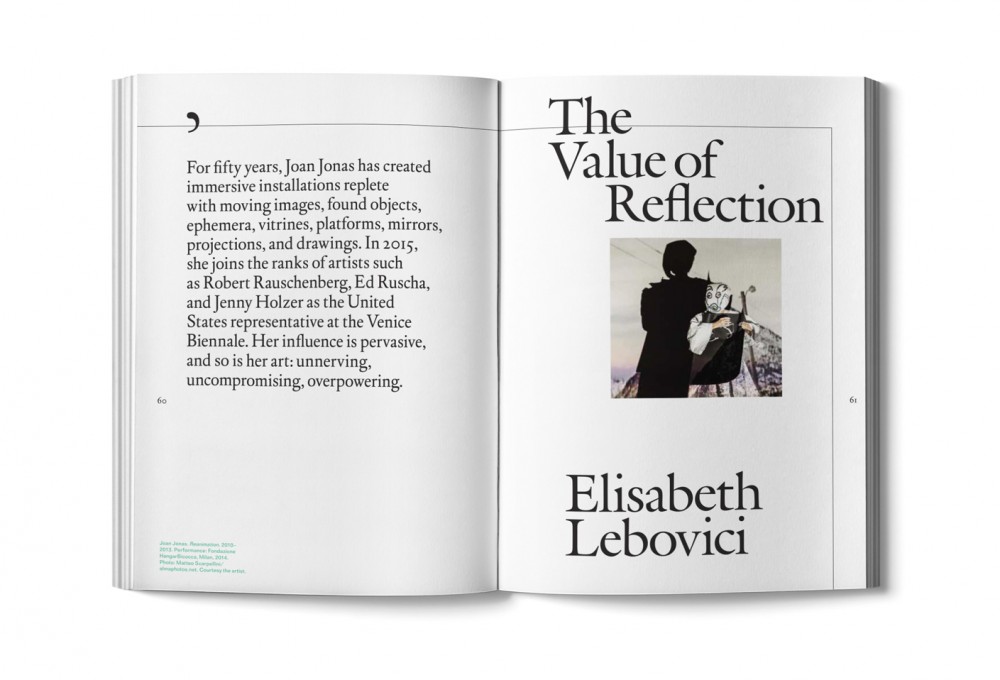

The centerpiece of the Summer 2015 issue is a roughly 5,000-word piece on Joan Jonas timed with her United States pavilion for the 56th Venice Biennale (see Everything You Need to Know About the Venice Biennale 2015 and The Most Outlandish Things Seen at the 56th Venice Biennale So Far). The writer, Elisabeth Lebovici, begins with an extended description of Jonas’s polyvalent work Mirage (1976/1994/2005), which combined 16mm, video, sculptures, and performance at New York’s Anthology Film Archives, only to interrupt herself with a candid aside to the reader:

Are you following this?

No?

Of course not. This thumping defeat of ekphrasis—the old Greek rhetorical tradition of understanding a work of art by describing what you see—as a workable basis for interpretation is precisely one of the principles I want to defend here.

But, weirdly, in light of this declaration, what follows are pages of short descriptions stepping through chapters of Jonas’s nearly five-decade career via individual works, doing little to secure poor Ekphrasis. It’s a bold move to do a print journal in 2015, to say the least. The reader in mind for this article is a Jonas novice, and, honestly, one would probably get a better sense of her work, faster, watching a series of ten one-minute-long clips online.

The piece is by no means bad, but it isn’t exactly a page-turner or penetratingly hardcore. And it does not venture far away from the type of artspeak one finds trammeling other publications, evidenced by enlarged pull quotes like the following:

In Jonas’s Mirror Pieces, acknowledging the presence of the spectator does not mean acknowledging the spectator as the artist’s doppelgänger. If the viewer is the artist’s double, it’s only an imperfect, dissident, unglorified, melancholic sort of double, rather like the cursed nymph Echo.

Business as usual.

The next essay is by Zachary Woolfe on the Bjorkpocalypse and its antecedents and aftermath (see Ladies and Gentlemen, the Björk Show at MoMA Is Bad and Is the Björk Show Debacle Klaus Biesenbach’s Ruin?). To offer a coda to a show that opened less than ten weeks before the magazine went to press (and which is still on view) is an admirable turnaround. Woolfe dexterously dispenses with a dead-on review and encapsulates the “wave of incomprehension and distaste wider and angrier than anything” he has seen in years. Then, after an express history lesson touching on figures from different spots on the 20th-century art-music continuum—Cage, Duchamp, Glass, and Reich, to name a few—he skips over pulpy questions like asking how Klaus Biesenbach should be punished, and continues onto a productive one: How has it become so agreeable for artists and curators to subsume music into the art world in such a dilettantish way?

The near total erasure of the boundaries delimiting contemporary art could have led to a grand interdisciplinary future. Instead, it seems to have offered a permission slip for artists to overlook developments in contemporary music and just make their own tune.

Amen! Good read.

Laura McLean-Ferris opens the third of Even’s three inaugural features with an evocative account of Anne Imhof’s performance “DEAL,” which was staged at MoMA PS1 this past January, and in which the artist gurgles buttermilk as she phases through a spectrum of extreme emotions (see Anne Imhof’s Massive Bunnies Debut at MoMA PS1). McLean-Ferris identifies the performance as an example of work that viscerally manifests the effects of networked society:

These artists are not taking on the task of picturing something too large to see (perhaps it’s worth recalling Stéphane Mallarmé’s direction to “paint not the thing, but the effect that it produces”). Instead, the feeling of the network is what’s crucial here. So, then, to the effects: here we have a generation of artists working with dependency, sociality, contagion, implication and guilt—issues that are both structurally germane to the art world and also increasingly relevant to the world beyond it.

Even magazine. Photo courtesy of Even.

Citing works by David Douard, Alisa Baremboym, and Ian Cheng as ones that eat themselves, McLean-Ferris relates them to last summer’s celebrity-spawned meme the Ice Bucket Challenge, which she manages to unpack as a compelling metaphor for cannibalistic power dynamics within social networks—a nasty, wet substitute for what she points out are usually represented by “fluffy clouds, immateriality, and a vague concept of sharing.”

She returns to the Imhof narrative then jumps into the “situations of deep dependency” in which art world players—from freelance individuals of all kinds to massive institutions offered money from dubious sources—find themselves:

When every actor in a network is aware, painfully aware, that they are part of the same social milieu, criticism becomes increasingly fraught.

It’s a great piece, and it’s a compliment to say that it feels cramped for space—there’s much more here that remains unsaid, and the meatiest, most original ideas are outweighed by descriptive passages (albeit vivid ones). This is essentially an op-ed, a journalistic genre missing from the art world as an able conversation starter.

Two of Farago’s own interviews are included as well. His talk with Beirut artist Marwa Arsanios yields fruitful perspectives on the Lebanese art scene past and present, and his questions to Belgian great Luc Tuymans produce this pearl: “I did for Condoleezza Rice what Andy Warhol did for Marilyn Monroe.” Both are solid, but nothing is out of the ordinary.

What’s much more novel is the format of the reviews in Even. Rather than a dozen blurbs on shows from around the world, four critics each gather three or four reviews along some common thread, hypothesis, or trend.

Karen Archey traces coolness and Zombie Formalism across three exhibitions: MoMA’s “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World,” a recent Reena Spaulings show at Gallery Neu, and the New Museum Triennial. Travis Diehl visits three LA shows—Pierre Huyghe at LACMA, Renée Green at the MAK Center, and Karl Holmquist and Ei Arakawa at Overduin & Co.—with the artists’ architectural gestures in mind. Jyoti Dhar offers a cross-sectional chronology of the New Delhi space 24 Jor Bagh by reviewing a 2011 show by Vishal K. Dar and Asim Waqif, a 2013 show by Raqs Media Collective, and a 2015 show by CAMP.

Even magazine. Photo courtesy of Even.

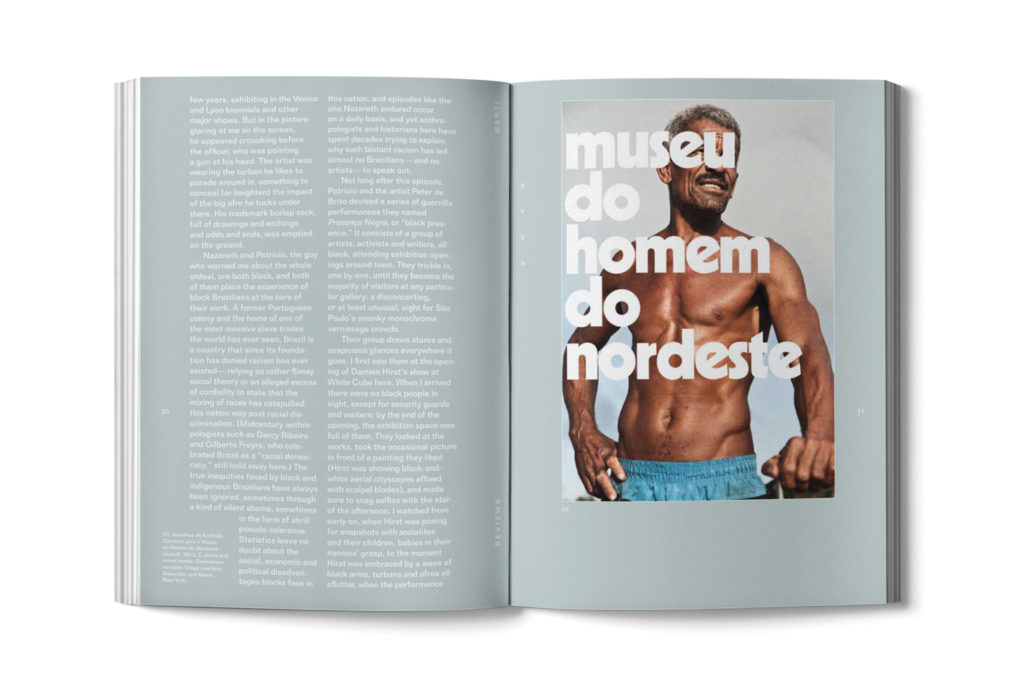

The best demonstration of how short-form reviews might be put in service of a concept greater than the sum of its parts, however, is from Sao Paulo writer Silas Martí, who explores Brazil’s endemic fascination with race and its component denial of racism via shows at Instituto Tomie Ohtake, Museu de Arte do Rio, Galeria Millan, and Galeria Leme.

Even, as a title, is odd. Plucked from art history, the word might refer to balancing the antipodal forces that stagnate the art world, but the magazine’s narrator uses it as often as possible as an awkward intensifier: “Here is a problem—a paradox, even,” “That seems to be the only possible way to understand where we are, or where we’re going, even,” “subscribe, even.” It’s neither catchy nor colloquial. But branding won’t interfere with a roster of mostly sincere and talented writers, will it?

Even’s maiden voyage should be considered a success, and if the journal stringently stays the course that avoids pretension, it could be the lifeboat from highfalutin malarkey it wants to be.