Galleries

Student Reveals How to Sue Richard Prince and Win

Will this result in a wave of copyright infringement suits?

Will this result in a wave of copyright infringement suits?

Cait Munro

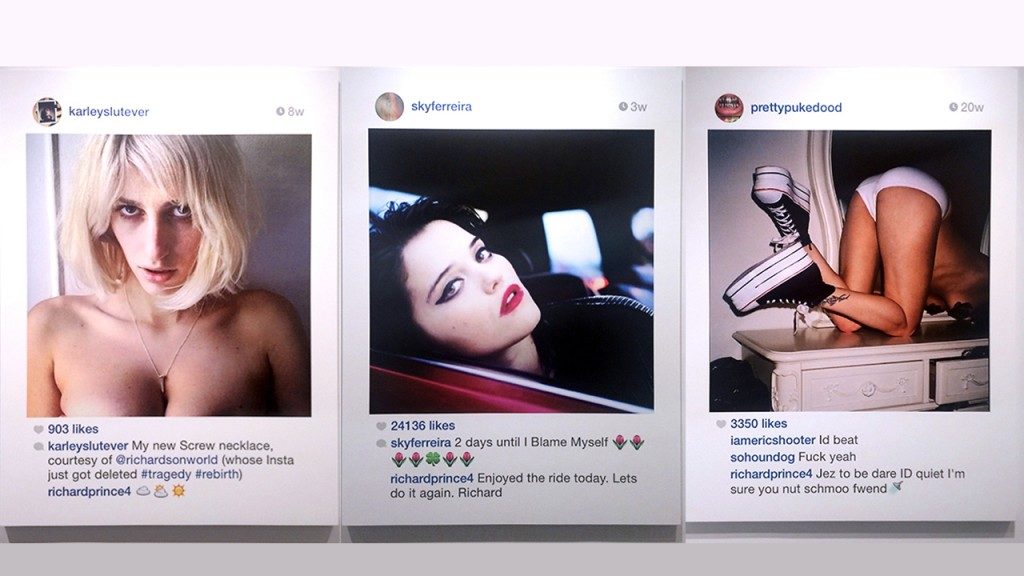

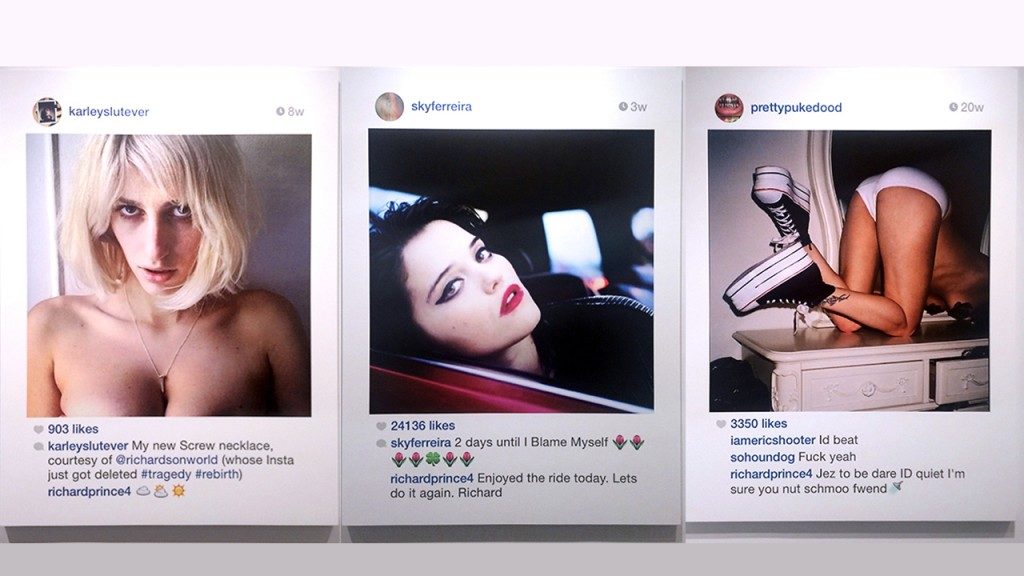

When controversy came calling a second time with Richard Prince’s Instagram-sourced “New Portraits” in May (which writer Paddy Johnson detested), several of his subjects spoke out.

Some felt flattered by their inclusion in the controversial series, and some struck back, but most felt they didn’t have the means to create a case against a blue-chip artist. “I’ve been asked, ‘Why don’t you just sue him?,'” Anna Collins, a college student whose picture was used in the series told Business Insider. “But it’s not that simple. I’m a 19-year-old girl and here is a rich, successful man.”

Richard Prince.

Photo: Courtesy of AP.

But how might a college student go about winning the case, especially given Prince’s massive victory against photographer Patrick Cariou in 2009? This question is the subject of a lengthy investigation by Nate Harrison of the photography site American Suburb X, succinctly titled “How to Sue Richard Prince and Win.”

Harrison, who is open about his own lack of critical appreciation for the series, which he calls “cynical opportunism masquerading as a critique of authorship,” posits that the key to winning a copyright infringement case against Prince would obviously lie in proving that the “New Portraits” don’t comply with fair use according to the Copyright Act of 1976.

Prince’s win against Cariou solidified his ability to pull from whatever source, as long as the resulting artworks can be perceived by a “reasonable viewer” as transformative. The key would be to prove that the “New Portraits,” despite Prince’s comments below the greatly enlarged images, do not transform the works enough to merit protection.

Installation view of Richard Prince, “New Portraits,” at Gagosian.

Photo: Courtesy of Paddy Johnson.

“[In Cariou v. Prince] the court essentially indicated that authorial intent is of lesser concern, because what ultimately yields meaning in a work is that which the reasonable viewer…brings to it,” Harrison writes.

Of course, a lot depends on just who this “reasonable viewer” is. Art critics and scholars—though many may openly despise Prince’s artworks—are actually likely, Harrison posits, to defend them based on the notion that if they are hanging in the rarefied realm of the art gallery, they are inherently meant to be understood differently than in their original context.

And yet there are no real aesthetic changes made to the portraits. Prince himself even admits that the comments he adds, which could be the real saving grace, don’t amount to much. “The language I started using to make ‘comments’ was non sequitur. Gobbledygook. Jokes. Oxymorons. ‘Psychic Jiu-Jitsu,'” he writes in a Gagosian press release.

Thus, “the reasonable observer variant of transformative fair use would spell trouble for Prince’s “New Portraits,” Harrison writes. Moreover, the portraits copy the “look and feel” of Instagram, which could even supply grounds for the social media site to file its own claim against the artist.

“Artists should be encouraged to explore the possibilities that copying provides,” Harrison concludes. “But that doesn’t absolve them from taking responsibility for their actions. Artists are obligated to the images they re-use. It’s important that they do critical things with them, and not merely reproduce cultural and economic capital for the one percent while feigning comradeship with the social media masses.”

So read up, Prince victims! The appropriation art master might not have as much leverage as you think.