Law & Politics

Richard Prince Moves to Dismiss Latest Copyright Infringement Lawsuit

Should an earlier decision overrule the new complaint?

Photo: © 2014 Patrick McMullan.Company, Inc.

Should an earlier decision overrule the new complaint?

Brian Boucher

Appropriation artist Richard Prince hopes a court will throw out the latest copyright infringement lawsuit against him, and has filed a motion to dismiss the case.

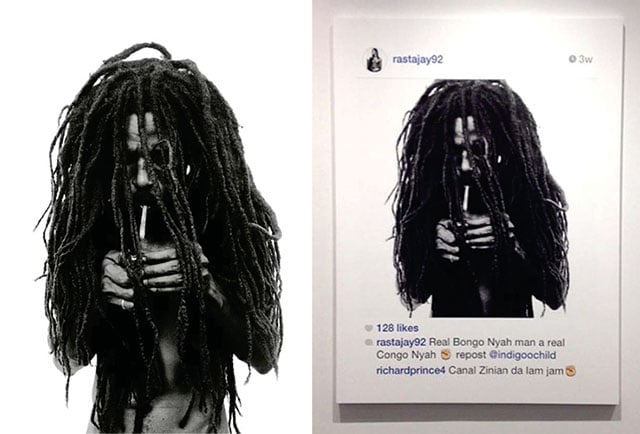

Photographer Donald Graham filed suit against Prince in January, asserting that one of the works in Prince’s 2014 exhibition “New Portraits,” at New York’s Gagosian Gallery, improperly used one of his photographs, showing a bare-chested Rastafarian man with long dreadlocks smoking a joint. Prince copied the image from a third party’s Instagram post.

Prince’s attorney, Joshua Schiller, of Manhattan firm Boies, Schiller & Flexner, argues that the piece is transformative of Graham’s photo, and thus should be protected under the “fair use” provisions of copyright law, because the central meaning of the work is as much in the social media context as in its appropriation of Graham’s photograph itself. He also suggests that the work should be protected because it does not affect the market for Graham’s output, which is another factor in fair use.

Legal experts surveyed by artnet News predict that the case could have major implications for intellectual property law.

Donald Graham’s photograph, left, and Richard Prince’s appropriation of it.

“In terms of the real estate of the screen, Graham’s image seems to dominate,” intellectual property lawyer Amy Goldrich, of New York firm Cahill Partners, told artnet News in an email. “But if you accept that what we are looking at is larger than the screen—the larger social media context—then the balance arguably changes.”

The exhibition that included the appropriation consisted entirely of large prints of screen grabs of other people’s Instagram posts, and provoked a round of outrage online among those who felt Prince had “stolen” their images.

“Mr. Prince’s New Portraits are novel, expressive works that transform outside material used as raw ingredients in the works’ creation,” says Prince’s attorney Joshua Schiller in an email to artnet News.

Schiller asserts that the Second Circuit of Appeals court’s decision in the landmark case Prince v. Cariou supports the dismissal of Graham’s complaint.

That decision found that the majority of Prince’s paintings in a previous show, “Canal Zone,” were protected under the “fair use” provisions of copyright law. Those works also used existing photos, also of a Rastafarian man, by French photographer Patrick Cariou.

In 2009, Cariou sued Prince, Gagosian Gallery, dealer Larry Gagosian, and Rizzoli, which published the exhibition catalogue. A March 2011 ruling sided with the French photographer, calling for the destruction of the remaining copies of the catalogue and the unsold “Canal Zone” paintings, but was largely overruled on appeal on the basis of fair use in April 2013, when the Second Circuit ruled that most of the paintings were protected, and sent the remaining few back to the lower court. Cariou later dropped his complaint on the remaining works.

“The Second Circuit recognized the transformative nature of Prince’s artwork in a landmark decision three years ago, and we believe the District Court will recognize the same here, as many reasonable observers in the media already have—that Prince’s artwork has a fundamentally different expression and meaning than Mr. Graham’s and promotes the progress of the arts,” Schiller says in the email.

“The fact that Mr. Prince is now appropriating from popular social media platforms like Instagram, as he has in the past done with tradition media like the New York Times and Time Magazine, make the current work challenged by the photographer Donald Graham just as deserving of fair use protections,” he writes.

In the email from his attorneys, Prince says, describing the “New Portraits” series, that he is simply using “electronic scissors.”

“The quote is fascinating, because Prince is effectively appropriating and updating his own language to describe what he did when he re-photographed the cowboys from the old Marlboro ads in the 1970s,” Goldrich said. “He talked about what he saw through the lens of the camera. It wasn’t just a printed ad cut out of a magazine. For him, looking through the lens transformed the cut-out ad into the photograph itself. Maybe Instagram did the same thing for the Graham photograph here. By this logic, he seems to be arguing that to make a screengrab is no different than to rephotograph.”