People

artnet News’s Exclusive Interview With LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner

Is it time to reconsider Shia LaBeouf's art practice?

Is it time to reconsider Shia LaBeouf's art practice?

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

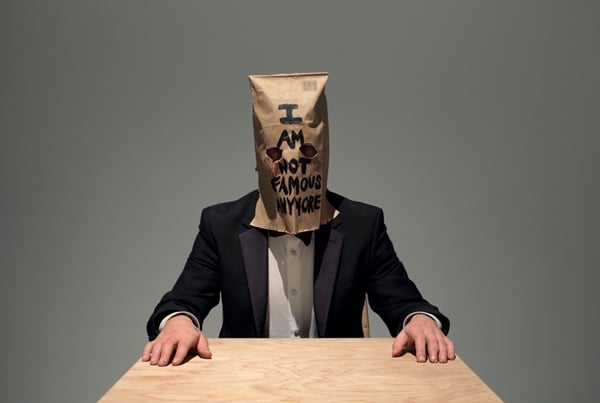

In February 2014, at the premiere of Lars Von Trier’s Nymphomaniac in Berlin, Hollywood actor Shia LaBeouf strutted down the carpet wearing a paper bag over his head that read “I am not famous anymore.”

Thus began the actor’s art career. What was seen and written about by many (including myself) as yet another bizarre stunt by a young celebrity, was in fact the debut performance of LaBeouf’s ongoing collaboration with artists Nastja Säde Rönkkö and Luke Turner. LaBeouf was taking a stab at conceptual challenges à la Joaquin Phoenix’s I’m Still Here performance or James Franco’s kooky art interventions rather than having—as was assumed at the time—a public meltdown.

Ultimately, an appreciation of this very particular oeuvre relies on LaBeouf’s celebrity status. And yet, LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner’s performances are entirely in a world of their own: part (meta)meditation on the effects of new media on our emotional lives, part post-modern take on classic durational performances in the vein of Marina Abramović and Sanja Iveković.

I approached the three artists to find out more about their activities. They sent their answers by email, reprinted here verbatim.

How did your collaborative practice begin?

Shia: i made a short film

line for line

shot for shot

of a comic strip

written by Daniel Clowes

i never attributed any writer’s name to the work

and never asked anyone if i could do it

the film won an award at Cannes

this was like a death

(one of the good things about modern times

is if you die horribly

around a cell phone camera/ twitter/ tv etc…

you will not have died in vain

you will have entertained millions)

i then had to answer for my fuck up

i quickly started looking for an answer

scouring the internet

looking for philosophies that would back my play

reading theories on appropriation

ran with that for a few days

before the ceiling came down on me

then i found the metamodernist manifesto

which read a bit over my head

lotta big words i had to look up

& i felt out of my depth

but then

there it was

one line towards the end

which struck me

“error breeds sense”

now i am far from an intellectual

but i like intellectuals

they teach me things

(i also hate philosophy but love philosophers –

cuz they can say whatever the fuck they want)

but this line

hit me hard

it was an epiphany

as i feel like my fuck ups

have been an impressively embarrassing welcoming

to the rights & duties of grown-ups in a way

like a puberty ceremony

i would call this moment

reading those words

my bar mitzvah

it read like

“play ball”

–

Luke knew Nastja from [art] school

showed me her work

I flipped

Luke thought she would have shared sensibilities

& when we all met each other in LA

a little tribe was born.

Luke: In all honesty, I didn’t know exactly who Shia was back then when he first got in touch, but his whole life was up there for the world to see—which seemed quite a peculiar thing in itself—so I was quickly able to gain a sense of his outlook on the world. I remember being taken aback by the degree of emotional openness Shia always seemed to carry himself with, through all the interviews and talk show appearances he’d ever done, right back to the Disney days of his childhood. That struck me as a rare thing; something that definitely cuts you out to be an artist. That, and the Sigur Rós video he’d done with Alma Har’el. Once I saw that, I knew he was the real deal.

Nastja: Luke contacted me after he met up with Shia in London and the three of us discussed creating something together. We all met in LA for the first time and there was immediate chemistry between us. So we started making work together and haven’t stopped ever since.

Luke Turner, Shia LaBeouf, and Nastja Säde Rönkkö, #IAMSORRY (2014).

Photo: Courtesy the artists.

Luke and Nastja, what interested you about the world of celebrity, coming from a relatively anonymous background? And Shia, what led you to explore fame from this particular angle?

Luke: The idea of celebrity wasn’t the thing that initially interested me in itself, but rather the potential for this public presence to serve as a locus of artistic discourse, to activate a multitude of disparate subjectivities, and to engage as broad an audience as possible. The reality is that the whole of the art world is relatively anonymous; it doesn’t directly engage the general populace to the extent that most artists would like it to. So, even though Nastja in particular had been an established performance artist in her own right before we started working together, the visibility that our collaboration enables has made our works exponentially more accessible and, hopefully, engaging and affecting for many more people.

Nastja: I have never been interested or fascinated with the worlds of celebrity or fame as such, and somehow I think this itself allowed me to make this work. I went into this collaboration with an open mind and no expectations on how the work would be received in the art world or with the wider audience. I wanted to create these works with Shia and Luke because it felt like such an unusual, challenging, and new way of working and making sense of the world, and I think as an artist this is always something that you are seeking. The key thing for me is to believe in what I am doing, and a big part of that is believing in the people I’m working with.

Shia: the star is a by-product of the machine age

a relic of modernist ideals

it’s outmoded

–

i was tired of the mainstream

I figured the ‘star’ concept could become a portal

through which the forces of transparency

might infiltrate the mainstream

The idea of the “star” could become a prime site

for the formulation of new stances

whose honesty might advance a more satisfying kind of affect.

Your first collaborative projects were mocked by members of the media at large. Was that something you were anticipating, or did it actually hurt your feelings?

Shia: of course

your magazine in particular

put out one of the most cynical headlines I’ve ever read about anyone

cynicism is corrosive to the human soul after a while.

Nastja: When I make work, I don’t think about how it is perceived or what people think of it. I don’t mean this in a naïve way, I am very aware of its implications and context within the history of my medium, but I trust my intuition and gut feeling, and so I did with this collaboration too. Mockery hurts, of course, but what really annoys me is when people write things and don’t check the facts and/or do their research about our projects or us beforehand.

Luke: I think there was a tendency, particularly early on, for both the wider media and factions of the art press to willfully misconstrue what we’d been doing as some kind of “bizarre meltdown” on Shia’s part, while disregarding the facts of the authorship of the work as that of a three-artist collective, even though we’d been openly laying the facts of our collaboration on the table the whole time. Of course, in a way this all feeds into our practice as a critique of the mechanisms of the art world, and the evolving narrative of such coverage is something that especially interests me. I find it quite telling that many of the first people to actually dissect our work thoughtfully were art students, rather than established art writers.

Naturally, we did expect some degree of cynicism from the media, but I anticipated that art writers would be able to step back and cast a critical eye over what we’re doing with regards to the relation between performance, the networks, and mainstream culture. However, I’ve seen many a critic fall into the trap of regurgitating tabloidy secondhand misinformation about our projects, describing what they imagine transpires therein as bizarre antics, without ever experiencing the reality of the works firsthand. It feels like this negates the difficulty of articulating the intended outcomes of our practice.

There’s an incredible and beautiful book by Jennifer Doyle that addresses this very topic, on Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art, which considers how the media often whips up so much of a storm surrounding an artwork’s “controversy” that the very real and difficult aspects of a work might never get addressed with any insight. Interestingly though, as Doyle herself noted recently, “pop culture journalists have been smarter about [our] performance projects than art critics.” I’d largely agree with that. So far!

Shia LaBeouf, Nastja Säde Rönkkö, and Luke Turner at FACT Liverpool in December 2015, during the performance #TOUCHMYSOUL.

Photo: Courtesy the artists.

Your work seems to be starting to be properly understood, and you are now working with curators and in institutional contexts. To what do you attribute this shift?

Shia: The only shift here

is that the media have a sense they are behind the 8 ball

(hence your request for an interview)

the art world has slowly begun to actually deal with the difficulty of the work

but it’s not changed the way we build our work

we build work according to people’s commonalities

which is not education or taste

but experience of mass media

the networks & human sensibilities.

Nastja: I think from the very beginning we had people who “got us,” also in the art world. There are curators and colleagues who have been supporting us from day one. I feel strangely about the phrase “properly understood” because I don’t think there is a proper or improper way of understanding our work, or any work of art. Some people are touched by our projects and some people are not, and either way is perfectly valid.

Luke: Right from the outset we’ve been doing our performances in these very same art contexts, so nothing has really changed on that front; just in the way it is being reported. It was always important to us that we situated our work amongst grass-roots artists and artist spaces, as much as these larger institutions. One of our very first performances was at Auto Italia South East in London, curated by Justin Jaeckle, who was incredibly supportive and inspiring. Likewise, the Stedelijk performance came pretty early on. But we also do projects at many lesser-known spaces and institutions. We want to reach out to as broad an audience as possible, and I really don’t think there’s any such thing as a “proper” curator or context. As long as the people you’re working with are engaged with what you’re doing, it seems that beautiful things can happen.

Installation view of LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner’s exhibition at Colorado State University-Pueblo, January 2016.

Photo: Courtesy the artists.

You seek to create a very real, almost bodily type of connection with your audiences, but do so by mixing real life interactions with technology. What’s interesting to you about this hybridization?

Luke: For me, the networks are real life; technology is nature. My works are always a reflection of this. I’m drawn to explore the new terrains and technologies of the networks, perhaps in much the same way as the Romantics were drawn to the sublime.

Shia: I don’t think “technology”

or more specifically the “networks”

are detached from “real life”

this is a big theme in our projects

we are in a state of hyper visibility

in the ’80s it was different

you just absorbed the media

the web makes everything egalitarian

now you have the civilian journalist with a cell phone camera

a twitter ticker feed on CNN

it’s a two way street

And our performance work is the embodiment of that two way street.

Nastja: For me technology facilitates or allows certain kinds of connections to happen between people. I am not so much interested in technology or the networks per se, but what we can make happen through these networks, how we can use them to become more human somehow. I feel privileged to have been born in the ’80s and grown up in the ’90s, before social media became an everyday thing and such a big part of our identity: somehow I feel I have seen and inhabited two very different kinds of worlds and ways of being in the world, ways of creating and understanding subjectivity. This is perhaps something that I seek to reflect on in our projects.

Another recurrent aspect in your work is the invocation of pure and raw emotion. Do you ever worry about falling into the terrain of sentimentality, kitsch, or even self-help?

Shia: art is about resonating with people

and with one’s soul

all good art is intimate to some degree

–

the way i see it we’re all lonely, all of us

not fitting in makes you lonely

makes you feel unloved

i think there is a very real relationship between loneliness & love

or sometimes we can’t recognize when we’re loved

i think the deal is you’re fully lonely

& the sooner we all embrace our loneliness

the healthier we are

it is about witnessing each other as individuals & saying:

“i’ll show you mine if you show me yours”

i think it’s our role in this practice to “show ours”

without demanding the “show yours” in return

our stuff is about un-aimed love

if it comes across as kitsch

or sentimental

that’s ok.

Nastja: Ha, I’m all about raw emotion! I don’t think there is anything cheesy or sentimental about expressing love or seeking connection. This is what humans do. I think people are afraid of love and that’s why working with emotions is challenging and these kinds of works are sometimes easy to dismiss as being sentimental/kitsch. I don’t worry about how this aspect comes across in our works because we are also aware of, and attempt to play with the humour and irony of it all.

Luke: When you bare your soul, when you take down your defences and open yourself to be moved emotionally within a performative, participatory art context, it’s surprising how the outcome rarely seems to be one of over-sentimentality or kitsch. I sense that we’re past that kind of knee-jerk response, both as artists and as an audience. The time of ironic dismissiveness appears to be behind us, and as a whole, our generation is yearning these types of real connections. Though our works do often play with irony on one register, they only work, I think, because the responses they generate are often utterly moving and sincere, to a degree that I never even thought was possible through performance.

Installation view of LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner’s exhibition at Colorado State University-Pueblo, January 2016.

Photo: Courtesy the artists.

Shia’s artworks are often mentioned in the same breath as James Franco’s, another Hollywood actor with a penchant for contemporary art. Do you find it annoying, flattering, absurd, or simply unavoidable?

Nastja: I think the only connection is that Shia and James Franco are both also actors.

Luke: And by reducing it to “Shia’s artworks,” one would already be straying from the essential context of our practice, and its inextricably collaborative authorship. To say that an active artist has “a penchant for contemporary art” would also make me giggle!

Shia: another word for “Hollywood actor” is “abstraction”

which is a way of making our work an “idea” or “suggestion”

rather than something of substance

proposing this question is the way the art world perpetuates the divide

you’re either a part of the refined art world

or you’re a part of its perpetual enemy “mass-culture”

but there is a realizable middle ground

our work is not bound by either the production rules of the mainstream industry

or the rules of the presentational logic maintained by the Art system

and I don’t see myself as an abstraction or –

“another hollywood actor with a penchant for contemporary art”

I think this is a way of assigning our work and others a lighter anatomic weight

and surmising that our sensibilities

could never accommodate your refined cultural outlook

–

(hollywood actor/ celebrity/ star/ famous person/ personality/ crazy man)

are all seen as un-virtuous titles by the art world

it’s a way to classify something as insufficient

& of alleviating the responsibility of having to

deal with the difficulty of the work)

–

Franco’s output is admirable

but his work has little meaning to me

–

I live and work as if there is meaning

though I know there isn’t

there is something incisive or instructive in living as if.

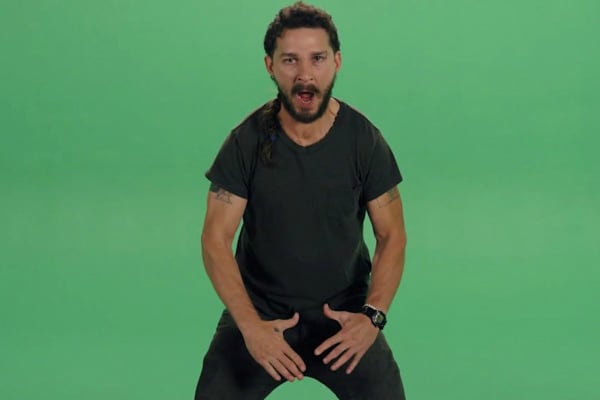

Shia LaBeouf in #INTRODUCTIONS (2015).

Photo: Central St. Martins.

How do you see, broadly, the pull between genuine emotions and irony in the contemporary art scene?

Shia: our practice has a both/neither relationship

between irony and sincerity

–

I find that some people in the art world

are incapable of recognizing art

when that art does not play the exclusive game of the art context

which is just context with a red ribbon around it

–

we’re using a platform to explore and intervene

from within

Art with a capital ‘A’ has ambitions for itself

in itself

to be autonomous

and self-contained

art with a small ‘a’ doesn’t need any ambitions in itself

we’re artists with our own ambitions

these need not be entertainment

but rather exploration

engagement

and yes

definitely affect.

Nastja: I think this kind of return to sincerity and values based on emotions can be seen in the world at large. I think irony is genuine too, a genuine emotional reaction to sentimentality. I don’t see this as black and white, but an oscillation, reaction. I would see it as an expected reaction to very particular environmental, political, and economic crises of our times. People are disgusted with excess and destructive behaviour towards each other and our planet. This kind of shift in consciousness and sensibility often shows first in the arts.

Luke: This shift is precisely what is being described as metamodernism; the mode of our contemporary culture as one of oscillation between positions of sincerity and irony, naivety and knowingness, apathy and affect. I see this kind of simultaneous irony and sincerity present in our work. Irony as a path to sincerity, rather than as an end in itself, born of a desire to do something heartfelt in a cynical world.