Art Fairs

Will Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s Bitterly Divisive Politics Poison the City’s Cultural Renaissance?

Eyes are on Chicago as it kicks off its first-ever Architecture Biennial.

Eyes are on Chicago as it kicks off its first-ever Architecture Biennial.

Ben Davis

Eyes are on Chicago as it kicks off its first-ever Architecture Biennial. The ambitious event opens under the heading of “The State of the Art of Architecture,” touting various conversations about the stakes of urban transformation—so some questions about culture’s evolving place in the economic and political life of the Windy City itself may be in order.

When I was in town recently, three stories fit together for me to form a kind of perfect collage narrative on the theme.

The first was Expo Chicago, a sprawling spectacle of 140-some galleries along Navy Pier, stately and professional and well-turned-out. Perched atop the great, glittering platform of the lake, you might have almost forgotten that the city had any real woes.

Hank Willis Thomas and The Cause Collective’s Truth Booth in front of Expo Chicago

Photo: Expo Chicago Instagram

The success of this four-year-old fair has a local point-of-pride feel. Its fortunes are particularly symbolic in that, before Miami became the indisputable center of the US art-market calendar, Art Chicago had held a major place since the 1980s. Its final incarnation shuttered in 2012, with its organizers bemoaning the torpor of Chicago collectors and the ever-more-competitive landscape of art fairs.

The story of the erosion of Chicago’s place by Miami, in fact, reads as a perfect parable of the cutthroat competition in an age when local economies live or die on the whims of fickle, hyper-mobile contemporary wealth.

Chicago’s hard-charging, bitterly divisive mayor Rahm Emanuel serves as “honorary chair” of Expo Chicago’s Civic Committee and is hip to the place that high-end art holds in the game of urban branding. Even before he was elected, he was telling Time Out Chicago that it was the city’s cultural amenities that had lured Boeing’s corporate headquarters from Seattle, and vowing, “we should restore the Chicago Art Expo’s rightful place next to the Basel Expo in Miami.”

One of his early initiatives, in 2012—the same year Expo launched—was to publish a 50-page “City of Chicago Culture Plan.” The Architecture Biennial advertises that it fulfills “Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s vision of a major international architectural event” as laid down in that plan.

One has to say that the Biennial is a great idea: Chicago has an unparalleled and largely untapped resource in its legendary skyline. As Crain’s Chicago Business wrote recently, “nobody in Chicago is rooting against its success.”

But Chicago is a city terribly divided, and the attempt to “redefine the city, particularly its creative sector,” as the Biennial claims to do, has not come without certain pushback from that sector either.

When local artist Marc Fischer, member of the group Temporary Services, was asked by the Architect’s Newspaper to answer some boilerplate questions about the importance of the upcoming Biennial for Chicago, he responded with a blistering open letter, much-shared via social media.

In addition to slamming the Biennial for being sponsored by oil giant BP, whose art patronage has become controversial after the UK’s relentless Art Not Oil campaign, Fischer also offered a series of alternative suggested questions for the paper:

What are you most looking forward to about Rahm Emanuel calling for the largest property tax increase in modern Chicago history?

What’s your favorite mental health clinic now that six of them have been closed by Mayor Emanuel?

Top 5 pieces of Chicago architecture chosen from the 49 schools closed by Rahm Emanuel?

What’s Chicago’s most architectural space used for torture in the secret black site in Homan Square?

Which skyscraper provides the greatest distraction from issues of real consequence that impact the lives of the Chicago residents that live everywhere else?

Good questions, all.

***

All of this was on my mind as I thought about the second big art story of that same weekend: the spectacular gala benefit preview of Chicago artist Theaster Gates’s new Stony Island Arts Bank, located on the city’s South Side in an abandoned bank gorgeously remodeled into a multifaceted art center. It is scheduled to open officially this weekend, alongside the Architecture Biennial.

The Stony Island Arts Bank

Image: Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial

Although it has never been the art-market center that New York is, Chicago has long been rich in artists. The city’s landscape has also been shaped by an electric tradition of social justice activism. One of the consequences of this configuration of forces is that Chicago has been particularly on the vanguard of what has come to be known as “social practice,” the much-talked-about genre of art-as-activism or activism-as-art.

The University of Chicago Press has recently been publishing a series dedicated to Chicago’s “social practice” heritage that now runs five volumes, and this strain of work remains so lively in the present that it is hard to keep track of all the worthy initiatives. Even as I was at Expo listening to Hans Ulrich Obrist toss his polished softball questions at hometown painting legends the Hairy Who, a space called Experimental Station on the South Side was hosting the “Drone Fair,” uniting artists and activists working around drone surveillance.

Theaster Gates is of this “social practice” tradition but also something else again. He rose to fame via the Dorchester Projects, an artsy renovation of a South Side house into a cool event space, and has steadily expanded the scope of his ambitions to encompass movie theaters, housing developments, and vast public art commissions.

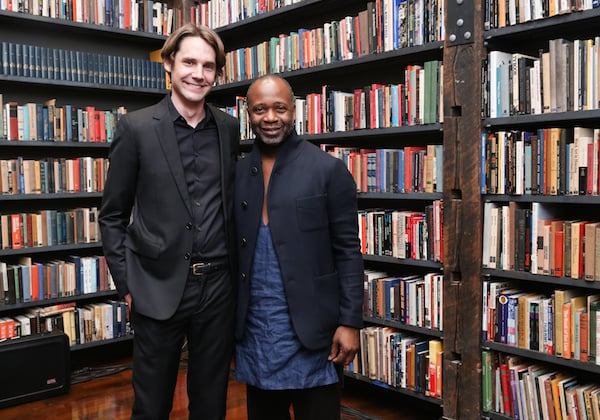

Rebuild Foundation CEO Ken Stewart and artist Theaster Gates

Photo by Kelly Taub/BFA.com, Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

At the same time he has by now been present at every major mainstream art-world event: the Whitney Biennial, Documenta, the Venice Biennale. He remains thoroughly invested in the traditional luxury-goods dynamic, maintaining a veritable art factory in a former Anheuser-Busch plant, and using the proceeds of gallery sales to fund his urban infrastructure projects in what he dubs a “circular ecological system.”

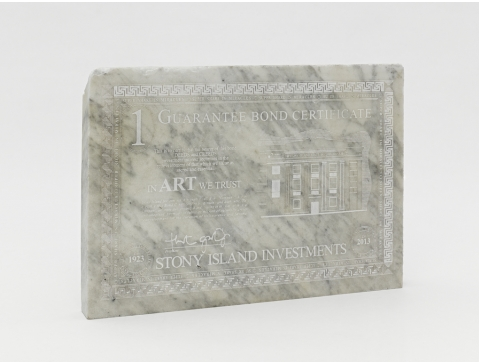

The same forces that have intensified inequality and devalued so many lives have also raised the value of “rich people things” to brain-numbing heights, and it is Gates’s distinction that he sees this not as an embarrassment but as an opportunity to exploit. Thus, the renovation of the Arts Bank was funded by selling marble scraps from the renovation as artworks at Switzerland’s Art Basel through his blue-chip, market-making London gallery, White Cube, raising a half-million dollars to transform this black, poor neighborhood.

Theaster Gates Bank Bond, on sale from White Cube

Image: Courtesy White Cube

You root for Gates because he is a son of Chicago and he is bringing amenities to Chicago’s African-American community, which has a history of being brutally mistreated when it is not being brutally neglected. What people say of the Architecture Biennial—that “nobody in Chicago is rooting against its success”—seems true of everyone I have talked to when it comes to Gates’s initiatives, though off the record and on it, skepticism has been growing.

Coming from New York, I know I have to clear my head a bit when considering the stakes of Gates’s endeavor: spatial dynamics are quite a bit different in New York or San Francisco, which are ruthlessly overbuilt and overinvested, and places like Detroit or Chicago, which have shrinking populations and acres of vacant space.

For artists in the former, the question is, “how do we avoid attracting attention and triggering gentrification?”; for artists in the latter, it is “how do we attract attention to trigger some small dose of investment?”

But the very fact that this question takes such a polarized on-off form is a symptom of the way urban space in our day is being stretched on the rack of inequality, with capital either too-present or not present at all. And the questions of displacement—not at all trivial in a city that has infamously systematically destroyed all of its high-rise public housing, dispersing vast numbers of low-income families—lurk somewhere on the horizon.

“[I]t’s fine for my neighborhood to change around me,” the artist once told Art in America. “It would even be fine if in five years, maybe because of me, the whole thing is lily-white.” Now he treads a bit more lightly around this topic, talking about the Arts Bank as being a place to have conversations about “active growth without gentrification, without new communities—how to remake the communities that we have already here stronger.”

Still, given the kinds of alliances he has forged, I wonder how consistent or frank or thoroughgoing these conversations can possibly be when it comes to the powers that have shaped and divided Chicago.

Splash magazine cover story on Rahm Emanuel and Theaster Gates

The Arts Bank could only happen because Rahm Emanuel threw himself behind it, gifting the bank building to Gates for a dollar. The two men are now wedded together in the world of civic photo opportunities; Splash magazine ran a photo spread last year of the two practically wrestling in the snow together, driving around the South Side and chatting about how they would transform it. Emanuel was the “honorary co-chair” of the “Build / Rebuild” benefit, which raised more than a million dollars, with seats going for $5,000.

Barack Obama, Emanuel’s former boss from his days as White House enforcer, penned a fulsome personal letter saluting the Stony Island Arts Bank initiative that Gates read out. Somehow I don’t think that the Experimental Station’s “Drone Fair” got such salutations from the President, currently the world’s most enthusiastic fan of robot-based aerial killing.

The Rebuild Foundation’s “BUILD / REBUILD” benefit at the newly restored Stony Island Arts Bank

Photo by Kelly Taub/BFA.com, Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Gates’s achievement is to have moved “social practice” from being the doughty, do-gooder cousin of mainstream market-oriented art to its star attraction, something positively glamorous. This formula has made him perhaps the most powerful artist in America, commanding six-figure prices and deploying his force-of-nature charisma to reshape a city.

But what happens when the vision of the real estate developers, politicians, and wealthy individuals Gates has staked his future in alliance with clash with the interests of the community he claims to serve? If this clash never comes, then the stakes of the experiment were a lot lower than we thought.

***

Which brings me to the third big story of the weekend, the third point of the triangle.

At about the same time the Stony Island Arts Bank was gearing up for its ritzy gala in Grand Crossing, the battle over Walter H. Dyett High School was coming to a climax in nearby Bronzeville.

The Dyett hunger strikers at a candlelight vigil on September 7, 2015

Image: Courtesy Coalition to Revitalize Dyett

The protest has swollen out of the mayor’s highhanded tactics in closing public schools in mainly minority neighborhoods. As Dyett was set to be phased out, neighborhood residents came together to form their own detailed plan to preserve the school, reopening it as a public academy based on “global leadership and green technology.”

The Emanuel-appointed school board proved unresponsive. Parents and activists viewed the closure as of a piece with the displacement of communities of color in Chicago. The sense of community voices being marginalized reached such a fever pitch that in August, a dozen parents, grandparents, and supporters decided to refuse solid foods until they were heard.

At multiple public meetings in the last month, the issue of Dyett loomed large. At one, protesters occupied the stage and chanted, “Rahm don’t care” and “The blood is on your hands.” The struggle gathered national attention.

Overpass Light Brigade and Milwaukee Teacher’s Education Association stage an action in solidarity with Dyett

Image: via Teachers for Social Justice

Faced with the uproar, at the beginning of September, Chicago Public Schools reversed course, announcing that it would reopen Dyett, but, almost out of seeming spite, not as the green technology school the community was calling for, but as an arts school. Calling the plan a compromise, the board said it would negotiate no more.

And so, the hunger strikers persisted, with Jitu Brown telling Chicago Tonight:

[W]hen the mayor imposed an arts school on the community, it was insulting and that’s why we didn’t stop. Because, what’s the number one industry for unemployment—the arts. We are not opposed to a strong arts program in our school, but we just want to see a school that prepares our young people to be the next scientists, the next civic leaders and the next doctors.

The insistence on the arts focus in education will be familiar to anyone who has read Emanuel’s 2012 City of Chicago Cultural Plan. Apparently, the attempt to impose this agenda by fiat is not the winning strategy he had counted on.

Jitu Brown announcing the end of the Dyett Hunger Strike

Image: Courtesy Teachers for Social Justice

The Saturday of Expo and the Arts Bank gala, the Dyett strikers at last broke their fast. They claimed the opening of Dyett as a neighborhood school as a partial victory, but said that it had become apparent that the powers-that-be would let them die. Jitu Brown addressed supporters about the lessons of the struggle:

[T]his hunger strike has taught people that we don’t have to fight by other people’s rules. And we can make the decision…if you could please repeat after me…make the decision…that you will not bow down to people that don’t love your children. Make the decision…make the decision…that justice is worth being uncomfortable for.

As engaging as Theaster Gates’s work is, you have to wonder why when he presents his plans for the South Side, Emanuel listens, whereas when Bronzeville’s hard-pressed, caring parents offer their own vision, they must literally risk death to be heard.

And yet, the activists have pushed back against the attempt to maul the fabric of their community, galvanizing the conversation about racism and education in Chicago and nationally. If the Stony Island Arts Bank wants to host a real conversation about what it takes “to remake the communities that we have already here stronger,” there is wisdom here about what that will actually mean.

In the wake of the struggle, Chicago Public Schools announced a slate of appointees who would set the agenda of the new school. Among the figures to sit on the new Dyett’s advisory board’s art committee, in fact, will be Theaster Gates. The protesters say they suggested a variety of people, but none were tapped.

They say that the battle—which is also the battle over what it will really mean to “redefine the city” culturally—will go on.