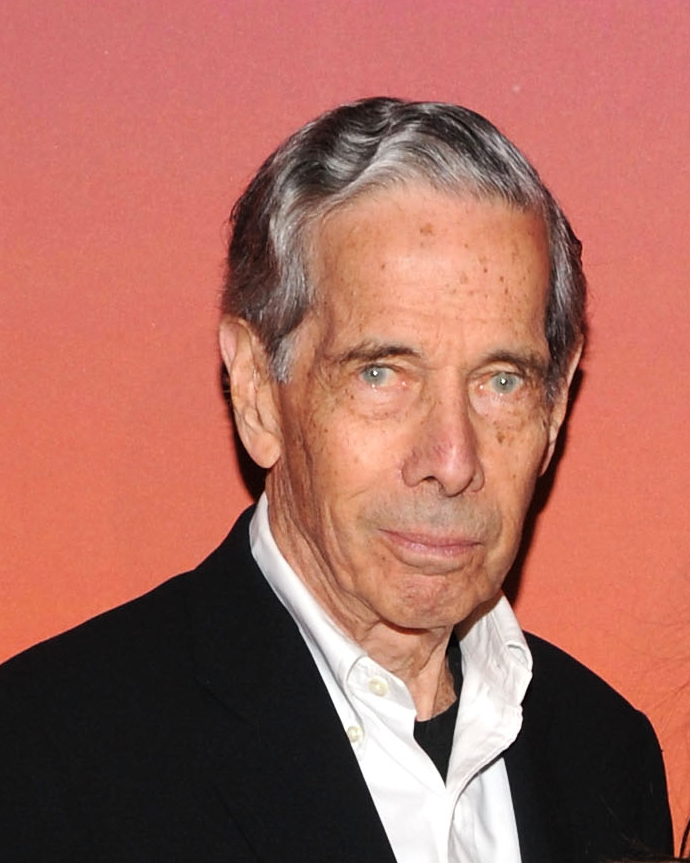

Getting his start in the frenetic hotbed of artistic creativity that was postwar New York, the art journalist Calvin Tomkins couldn’t have found a more chockablock scene to explore for the history-making profiles he wrote for the New Yorker. At the same time, the artists he profiled—ranging from Marcel Duchamp to the Jasper Johns/Robert Rauschenberg/Merce Cunningham group to, later, Cindy Sherman, Chris Ofili, and other modern-day art stars—could not have been luckier. In Tomkins, these artists not only found a chronicler, but a true understander, someone whose reporting could pick up the conceptual threads and tease out the real-life backstory necessary to nestle their great art in an all-important context. His profiles make artists human, allowing other humans to understand their art.

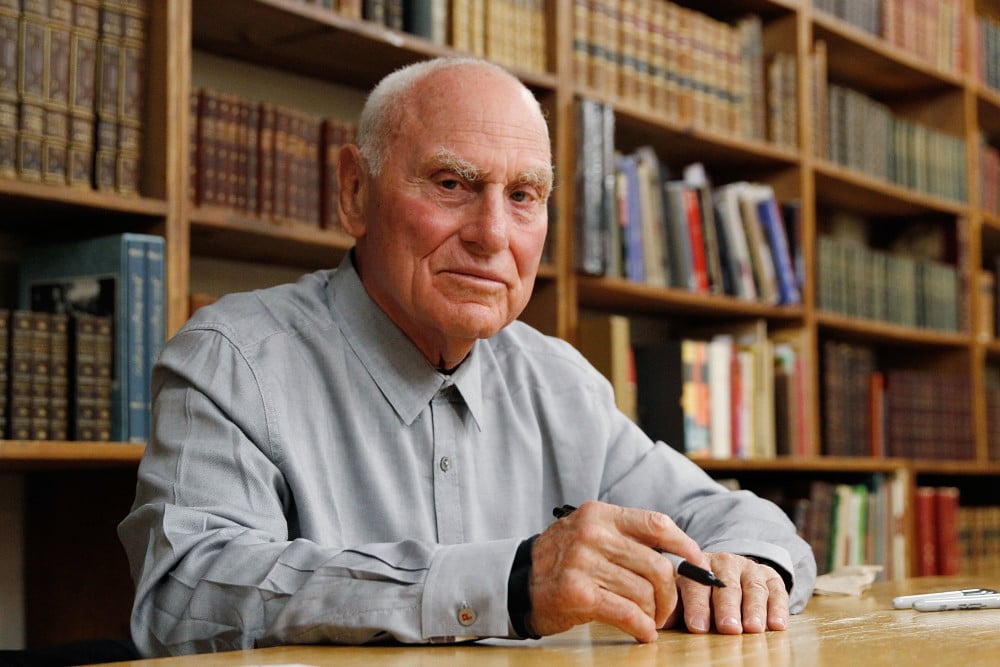

But how does he do it? And why do these secretive artists let him? Here, in the conclusion of a two-part interview, Artnet News editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein spoke to the veteran 94-year-old journalist and author about how he goes about plying his mysterious and enlightening trade.

You can listen to a condensed version of this interview here on Artnet News’s Art Angle podcast.

Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel. Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images.

Let’s talk about your own art, which is the art of the profile. How do you go about choosing who you want to profile? And then, after you make that choice, what is your process from there?

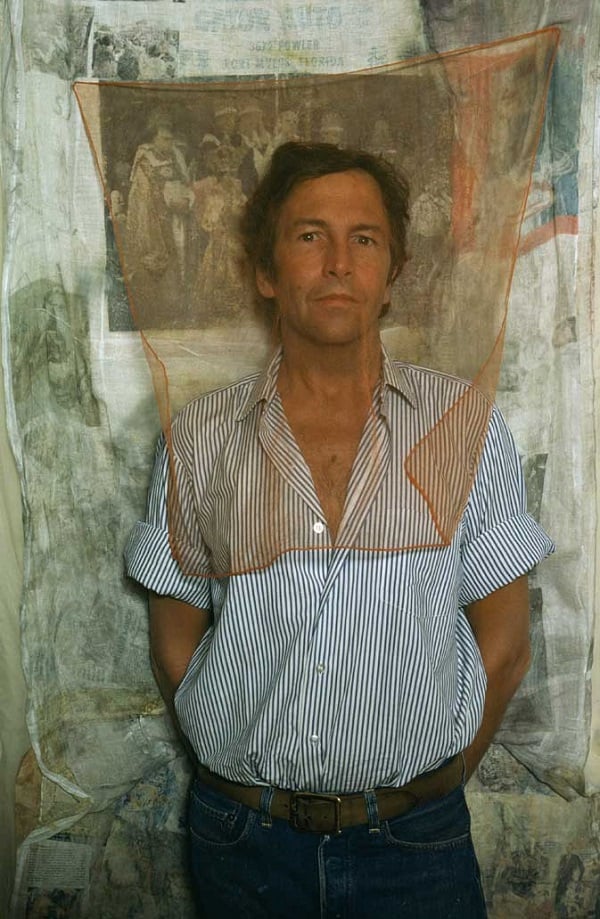

In my case, it was always a matter of one thing leading to another—the [Jean] Tinguely profile led to [Robert] Rauschenberg, which led to John Cage and Merce Cunningham, and back again to Duchamp. I didn’t think about this beforehand, but it just so happened that these first artists had many of the same approaches and ideas about art. And I think a lot of this came from Duchamp, although each one of them had reached his own way of working before being really aware of Duchamp. Bob Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns went down to the Philadelphia Museum in the ‘60s to see the work—they had never seen it before.

Duchamp had sort of been forgotten, but they had somehow gotten on the same wavelength—that art was maybe not what people had thought it was, or that it could be different. It could involve change; it could involve chance measures. And Duchamp had opened this up, of course, with his “Readymades,” which are common manufactured objects that are transformed into art by the artist who chooses them and signs them. Although in Duchamp’s case, he never thought of them as art objects. He said that he chose them with absolutely no aesthetic, because they had no aesthetic appeal.

Years later, he was having a public conversation with Alfred Barr of the Museum of Modern Art, and Barr said, “We know that you’ve always said that the ‘Readymades’ have no aesthetic appeal, but why is it that some of them—quite a few of them—are now so beautiful to look at?” And Duchamp said, “Well, nobody’s perfect.”

The editor of the New Yorker, David Remnick, has compared you to a “portraitist” in the way that you go about your work—which is a very specific term to be using when talking about an art journalist. As somebody who has studied more than a few portraits over the years, what do you think are the necessary ingredients for creating a true and lasting portrait of an artist?

Rauschenberg always spoke of his work as a collaboration with materials—he didn’t want control, he didn’t want to make one thing subject to another, he didn’t even want to choose colors. By giving up control in that sense, he and the other artists felt they were working in a new field of human awareness, that what they were doing was experimentation and you didn’t want to try to control where it was going, because they wanted to go beyond art, or beyond where art had been.

So, from Rauschenberg, I got this idea of art as a collaboration, and I thought to myself, “Why can’t profiles be thought of as a collaboration?” And this became one of the things that I looked for—artists who I felt could be interested in this idea of collaborating, of exploring territory that maybe that they hadn’t explored themselves, and finding out new stuff. But aside from that, I’ve never had any theories about how it could be done in every profile. Almost every profile has been unlike the last and a certain strain of personality can lead to a different tempo of writing. I just try to leave myself open enough to pick up the sometimes-unspoken currents.

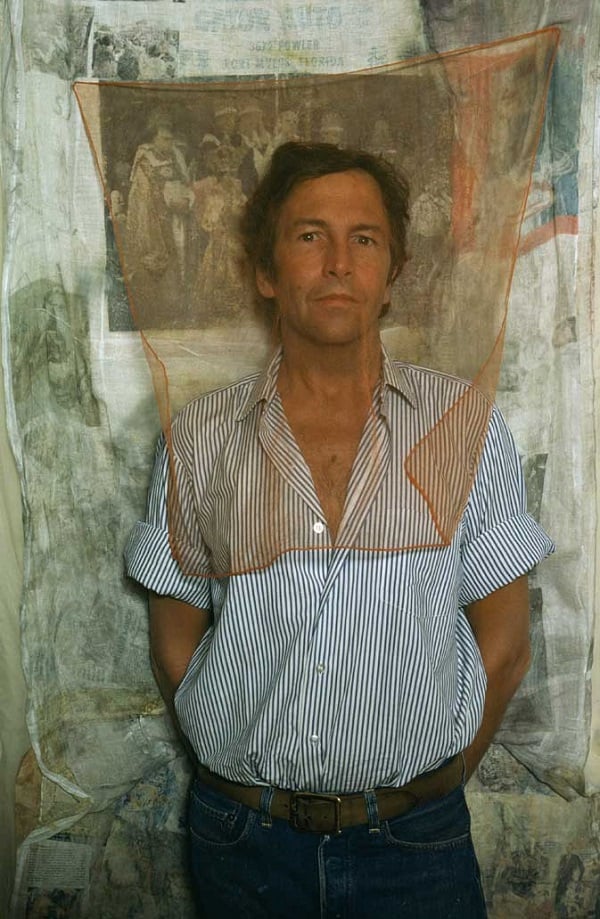

Robert Rauschenberg (1974). Image: Photograph by Art Kane/arttattler.com

That’s a fairly profound theory of profile writing. Because here you’re saying that Cage, Cunningham, and Rauschenberg were welcoming chance into their creative process so that one plus one could equal five, and then you’re the journalist coming into their studio to draw what you can out of them and add the details of everyday life that you’re able to imbue into their creative process, generating a result that is incredibly additive to the art itself. Is that something that you’ve found works?

Yes, I think it works. And I think it goes along with the kind of learning curve that each and every profile is. It’s a learning experience for me and maybe sometimes for the subject—we’re not coming at it from fixed positions. We’re not talking a lot about technique, or about how things are done. But there are exceptions. With Jasper Johns, who I tried for 30 years to get to agree to a profile, he kept saying, “I have nothing to say about my work.” Finally Dodie [Kazanjian, Tomkins’s wife and a fellow journalist] suggested, “Why don’t you just get together for lunch and try it, just to see how it goes. If it’s uncomfortable for either one of you, then just call it off.” And Jasper said, “Okay,” and we got into a profile.

But it was that different kind of profile. With Jasper, he never wants to talk about the meaning of his work, or what it signifies. He doesn’t feel that he should have to discuss that, and sometimes maybe he feels he doesn’t really know. But he was very good about technique, with talking about the process of working with hot wax for those encaustic paintings. I don’t think it was a philosophical approach by either of us, but I felt that, in the end, he collaborated.

My favorite story I’ve heard about Jasper Johns is that a curator at the Whitney once called him up and said, “Hey, Jasper, how’s everything?” And he said, “How could I possibly know that?” And I think this kind of gnomic, reticent artist is somebody that you’ve specialized in cracking. What kind of access do you need in order to do your best work?

The ideal is what David Remnick calls somebody who will “fill your bowl.” You just turn them on and they pour forth their lives into your lap. There aren’t too many people like that. But I don’t think there’s any particular method or course to a profile. I mean, I get to know them a little bit beforehand, or try to, and it depends on the subject how far or in what way we get into it. It keeps being a different experience.

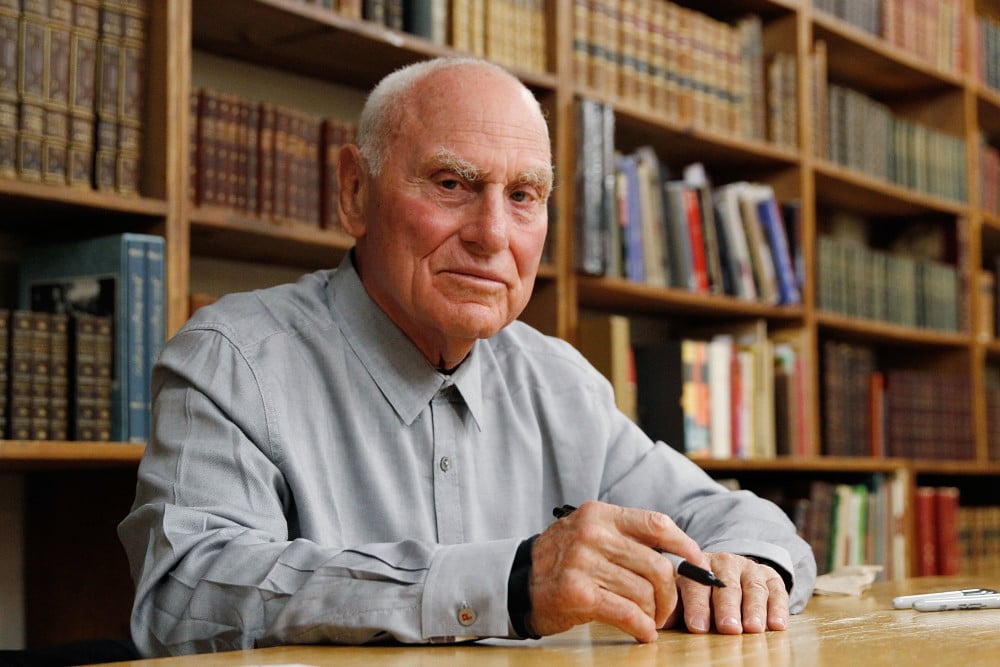

Richard Serra. Photo by Mireya Acierto/Getty Images.

Have there been any artists who have surprised you, either in how difficult they were to profile, or in how easy they were? Who was the rudest?

I think a candidate for that would be Richard Serra. I wasn’t at all sure he would agree to it, because a few years earlier I had written about his Tilted Arc in New York [a massive public art sculpture in Foley Federal Plaza, near City Hall that provoked a firestorm of controversy]. A lot of people in the vicinity hated it, and I wrote about it, saying something to the effect that public art requires different approaches than art for museums or private homes. And he was very offended by that and didn’t speak to me for two years.

And then, eventually, that was no longer the case, and he was doing such magnificent work that I thought I really couldn’t not try. It became a slightly painful but very rewarding experience to watch some of these huge walls of steel come together and be installed. The amazing thing always was that, for all this huge amount of weight, there was a lightness to them. There seemed to be a movement up and out, and I didn’t know how that happened, but that’s not the kind of thing he could talk about.

He did want to control the whole thing—and that persevered until the very end. When the piece was going to press in the New Yorker, he called us and the photo department saying that he didn’t want them to use the photographs of his work that he had agreed to use. He said, “I have just finished a new piece in New Zealand and I’m going to photograph it and I’m going to send it to you, and I want you to use those.” And so we got three photographs of a long, low piece in the landscape, going over the hills, like a wall but sort of undulating.

The next day, he called and he said, “You can use the one where the sheep on the right. But you cannot, under any circumstances, use the one where the sheep is on the left.” And besides wondering why he didn’t tell us that the first time or why he sent those ones in the first place, I know right away that the one that the New Yorker would have chosen would have been the one with the sheep on the left, which they had, and he was absolutely furious. But they wouldn’t change it—by that time, they had spent so much money pulling out one layout and putting in another that they weren’t going to change it again. But, up until the very end, he was trying to control.

I have to say, you got your revenge a little bit. In your David Hammons profile, a Richard Serra sculpture makes an appearance when Hammons is relieving himself onto a work of art. I think the photographer Dawoud Bey has even immortalized this performance in some photographs. I’m surprised you didn’t print those.

Um, the New Yorker is still a little resistant to nitty-gritty.

You have profiled so many great artists over time, and I know you said that you haven’t developed any overarching theories, but is there anything that unifies them to give you some insight into what makes a great artist tick?

Quite possibly there is, but I don’t know what it is. To me, art is still a mystery. I’m a Duchampian in the sense that I believe it’s impossible to define, and it’s always going to be changing. I think some of the same elements that made a great paining in the 16th century would be in a work by Richard Serra, for instance. But there are still so many differences. It’s interesting that the art of painting took 300 years to bring to an absolute high point, and then people stopped painting. But now it seems to be coming back, and there are artists like John Currin and George Condo who have rediscovered Renaissance painting techniques, underpainting, veneers, and all sorts of things. So nothing really gets lost. Everything just gets more complicated.

Édouard Manet, Olympia (1863). Image: Courtesy of New Directions.

Painting is now incredibly important again in part because there is a movement within the art world to start bringing people who have not yet been represented into the mainstream cannon. Often, this involves people who are not white and male, and one way that this is playing out in the art market right is a great wave of interest in portraiture of people who have not been previously widely represented in art. This is honestly par for the course across journalists who have been working over the past couple of decades, but, out of any cohort, the majority of the artists you’ve profiled have been white male painters. Out of the 82 articles featured in your Phaidon collection, 72 are male, and about as many are white. Now that you’re in a position to look around at what is happening today, and to look back into the past, how do you understand this huge shift in the way that art is peopled in the public consciousness?

I think it’s wonderful. I think one of the most exciting things going on in the art world now is the number of terrific young African American women artists who have emerged. It’s interesting that so many of them do paint, and paint figuratively. Quite a few of them seem to want to present themselves or their ancestors in situations that have been used for centuries by white male artists, the court portrait or the interior. They seem to want to see black faces in those kinds of landscapes, and it’s fascinating. There was that great show just a little while ago about the black model in 19th-century art, with a particular focus on the model in Manet’s Olympia. If you really look at the painting, the image of the black model is larger than the image of the Olympia—it’s really dominant, but for a long time, all you saw was the white nude. I think that we’re learning very quickly to see difference, different ways to do it, different openings for figurative art, but not so much abstraction, in this new wave.

It’s amazing to think that painting is really one of the most ancient forms of technology—it’s basically wet dirt on a rag—but this is really where the vanguard of art is today, in terms of the politics of representation. What are some other ways that art has evolved over the whole course of your 60 years at the New Yorker that you find really compelling today?

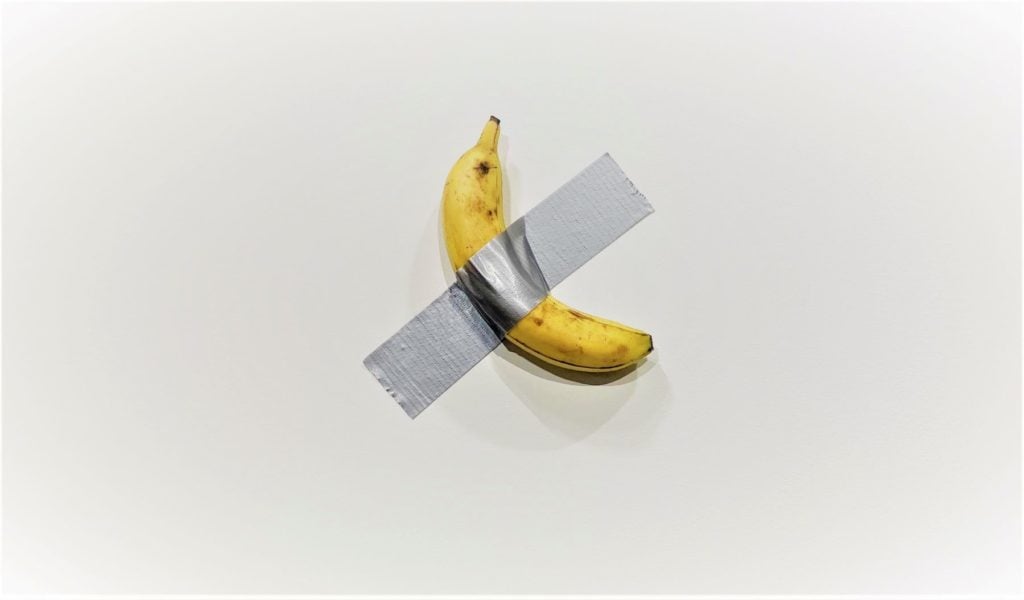

It certainly has opened up to all sorts of different possibilities—that art can be video, film, performance. And Duchamp is often is often blamed for ruining art, that he’s the one who opened the door to all this terrible, mediocre, sort of lazy art that we do see a lot of, along with the more important art. But it also gives us artists like Maurizio Cattelan, who has put images into the world that you are not going to forget. Who’s going to forget the Pope in his full regalia just after being struck by a meteor, or the kneeling figure who, when you walk around to the front, you realize is Hitler? And the big question hits you: Would God forgive Hitler? Conceptual art is many, many things, but one of them is this ability to deal with very big ideas.

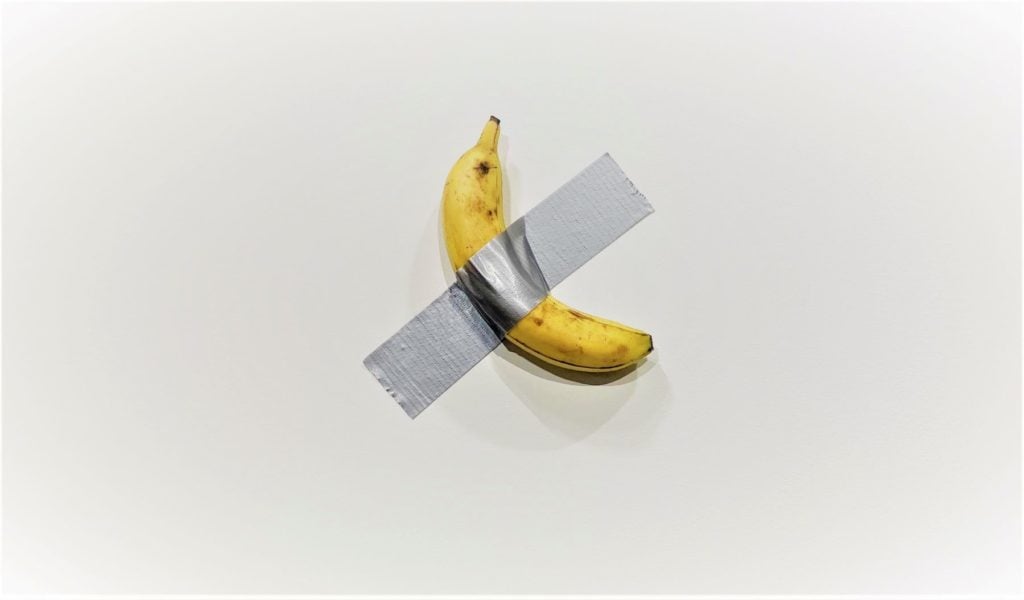

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, seen at Art Basel Miami Beach. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

I have to ask you, as a reigning Duchamp scholar, what do you make of Maurizio Cattelan’s banana that has created this enormous international furor in the press? What does this mean about the world that we’re in? Is it just a circus act and we’re monkeys dancing around this cultic banana?

Well, of course, the joke is that anybody thought it was worth paying $120,000 for. This is the joke. There are plenty of artists who put little, miserable pieces of string or something on the wall, and they’re quite serious. But this is an artist who’s professionally not serious. He’s making fun of everybody—making fun of the art, of the audience, of the buyer, of the gallery, which I think is very therapeutic. It’s great fun, and it’s very invigorating to have everything called into question.

The piece is called Comedian, which certainly supports your interpretation.

And we must not forget that the piece before that was a solid gold toilet that was installed at the Guggenheim Museum, fully functioning.

With all these slippery characters, do you believe everything that an artist tells you in your reporting process?

That would be disastrous. Very often, an artist is putting you on. I can never make up my mind about Jeff Koons when he talks about his work having this moral duty to relieve people from their shame and guilt over sexuality. You think he’s kidding when he says that, but he isn’t. He’s perfectly serious. The difference between Jeff Koons and Marcel Duchamp is that Jeff Koons is always sincere, and Marcel is never sincere.

Now, the original Lives of the Artists by Vasari was published in 1550, and many of those artists remain renowned today. In your book of 82 profiles, how many do you think will last?

In every age, the consensus on the greatest artists always narrows down to relatively few. I think in an art period, what you have is a great many artists who are not great but who are very good; and then artists who are not so good; and a great many more who are not good at all. But the field is much wider [today], and we don’t know what art is going to be like in the future. Duchamp was very pessimistic—he said that art was becoming so commercialized that husbands will pick up a little art on the way home to give to their wives. I sometimes wonder about all these shops on Madison Avenue and elsewhere that are going out of business—maybe they can all become mini-museums for not perfectly good art.

As somebody who has gotten Jasper Johns and David Hammons, who are the remaining big-game-hunting artists that you really want to nail down?

Well, I missed a couple. I didn’t get to Ellsworth Kelly, and there were a lot of women I’m really sorry I didn’t get to, like Eva Hesse, Lee Krasner, probably some of the people in the Ab Ex period.

Who is next on the list?

Offhand, I can’t think of anybody, but it’s probably because I’ve been sort of rushing it the last couple of years because I’m 94, and I don’t have more than 30 years left. I’m kind of tired at the moment, but that will pass, and I’m sure there’ll be others. I have others in mind—I was just talking to David Remnick about it this morning, but I’m not allowed to divulge who. That’s the omertà of the New Yorker.