Art World

A Brief History of Animated GIF Art, Part One

From found art wonders to Cory Arcangel, how a digital art form came into its own.

Courtesy the artist.

From found art wonders to Cory Arcangel, how a digital art form came into its own.

Paddy Johnson

What does the history of GIF art look like? This is a tricky question to answer because while there has been no shortage of animated GIF exhibitions, there is a dearth of documentation. Bond Street, a Brooklyn-based gallery that hosted Laurel Ptak’s exhibition “Graphics Interchange Format” in August 2008, no longer exists and neither does its website. “Save for Web,” a GIF exhibition that opened in August 2009 at Xpace Cultural Centre in Toronto has its own 1.0 website at Angel Fire, but no install shots or GIF slideshows. The same is true of the non-profit digital arts organization Rhizome, which heavily promoted its 2006 exhibition, “The Animated GIF Show,” on MySpace, and hosted the show in San Francisco.

This poses a problem because it means it’s much more difficult to piece together a history of how GIFs have been used in an art context. That history isn’t going to be told in one article, but given the pervasive lack of documentation, an overview is essential before key moments are completely forgotten.

The following selection is by no means comprehensive and, full disclaimer, will draw at times from the GIF exhibition I curated in 2011 for Denison University, which was also called “Graphics Interchange Format”. We’ll begin by covering the years 1998-2006. And of course, in the tradition of the collaborative Internet, I invite you to suggest your own additions to the list through social media so we can create a more broad and comprehensive account of the ways that artists have been using GIFs and why that history is so important.

MTAA Reference Resource, Simple Net Art Diagram (1997).

Courtesy the artist.

THE EARLY YEARS: 1997–2008

Simple Net Art Diagram is the earliest and perhaps the most enduring animated GIF for its provocation to participate. In 1997, the two-person artist collective MTAA released it to the public domain for remixing. Artists don’t generally license their GIFs—Internet users usually assume they can do what they want with them—but MTAA’s gesture was an invitation to join a dialogue. The image itself is an illustration of two computers with a red flashing lightning bolt between them; it pinpoints communication as the core purpose of art. This was not merely a diagram, though, but an invitation to other artists to locate and define art for themselves through the manipulation of the image. Now dozens if not hundreds of “Simple Net Art Diagram” GIFs exist, each offering a different theory about where art happens. These range from Kevin Bewersdorf’s 2008 “The Art Happens Here,” which locates art in the body and the heart, to Jim Punk’s sprawling diagram suggesting that art may be entirely buried online.

Chuck Poynter, Dancing Girl (1995).

Via Real_Dancing_Girl.

Olia Lialina, an artist and respected scholar of the amateur web, described herself as animated GIF model, and maintained a collection of several GIFs in her likeness. The GIF above, created by Chuck Poynter in 1995, was of particular interest because of a small blinking pixel to the left; Lialina views the pixel as a mark of authenticity.

Between 1998 and 2002, Rhizome commissioned artists to produce splash pages for its website. It’s hard to imagine landing pages like this functioning on today’s frantically paced web, but in a time of modems and slow-loading websites, these splash screens were a fast way to introduce viewers to the kind of content one might expect on the site.

Cory Arcangel, Super Mario Clouds (2002).

Courtesy the artist.

Cory Arcangel‘s Super Mario Clouds is one of the most iconic animated GIFs today and, in fact, has become a favorite background choice on the blog I run, Art F City. These clouds come from Nintendo’s Super Mario Brothers game, and relate to Arcangel’s early work hacking Nintendo games. Like many GIFs, this one is best viewed when tiled; a seamless page full of clouds is far more visually appealing than an isolated cube. Either way, the simple beauty of this sky paired with a now-dim nostalgic memory makes this GIF extremely effective.

Still from Paper Rad’s homepage.

Paper Rad is a now-disbanded art collective that was split between Pittsburgh and Providence and had three members; Jacob Ciocci, Jessica Ciocci, and Ben Jones. Their website, which was launched in the early 2000s, is a maze of linked images, blinking GIFs, and bright colors. Paper Rad refers to that trademark look as “Dogman 99,” a reference to Danish filmmaking movement Dogme 95. According to the collective, their style guide mandates the following: “No Wacom tablet, no scanning, pure RGB colors only [an additive color model which begins with red, green and blue light], only fake tweening, and as many alpha tricks as possible.”

Kelly’s World of Cheerleading.

Homestar Runner (Sweet Cuppin’ Cakes).

The GIFs above were not made with artistic intent, but collected by artists who found artistic interest in them. Occasionally, artists would enlarge small GIFs. This particular collection was put together by artist Tom Moody in 2003, and further edited by yours truly for this list. I am particularly interested in Bunchies, Roel Van Mastbergen’s running green llama-like creature, for its Botox-like smile.

The year 2003 was a busy one for the animated GIF. MySpace was founded that year and quickly became a platform that was for the dissemination and exchanging of GIFs.

Tom Moody, OptiDisc (2006).

Courtesy the artist.

The throbbing lines of Moody’s OptiDisc create a hypnotic effect. As I have written previously, “Like much of his work, the image embodies the ideals of modernism, generating a push-and-pull between emotional awe and reason. Their emotive qualities last only as long as Moody allows a reverence for technology—in Moody’s world modernism is only an afterimage, its spirit eventually replaced by mechanical functionality.” It’s significant that this work is among the first GIFs meant to be displayed both online and in the gallery. It was first exhibited at Paul Slocum’s And Or gallery in 2006.

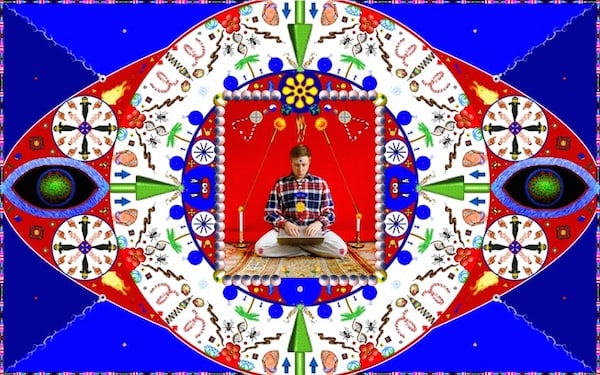

Still from Kevin Bewersdorf, Animated GIF Mandala (2008).

If GIFS were once known merely as “those annoying blinking things,” Kevin Bewersdorf‘s Mandala takes that reputation and amplifies is a thousand times. The GIF shows Kevin Bewersdorf meditating, surrounded by bouncing, twirling, blinking, swirling, waving, and gyrating GIFs. What makes this GIF so remarkable is that it incorporates hundreds of independently moving found GIFs with very little compression (a technical accomplishment achieved with the help of Paul Slocum), allowing the artist to depict each component with great clarity. The original piece was displayed as a full-screen video, but the smaller GIF version is still amazingly detailed.

Stay tuned for parts two and three of Paddy Johnson’s history of GIF art.