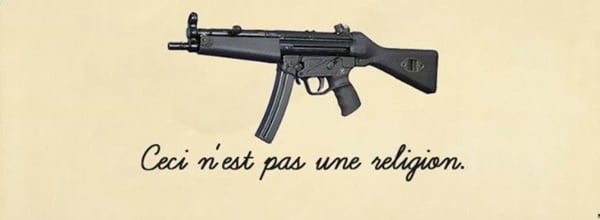

‘This is not a religion.’

Photo: Stephen Stardom via Twitter @stephen_strydom.

When is the last time someone killed a visual artist over a controversial artwork?

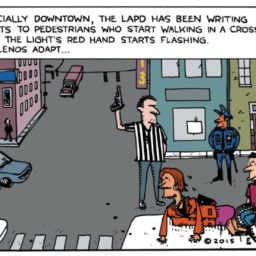

The horrifying attack this week at French satirical weekly magazine Charlie Hebdo, which resulted in a dozen deaths, has done nothing if not raise questions. Among them, to our mind, is, Why do extremists kill cartoonists and not artists, even when people profess to be outraged at the artists’ works? What does this difference say about popular art versus fine art?

Tuesday’s attack is only the most recent instance of murderous outrage over cartoons. Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published drawings satirizing the Prophet Muhammad in 2005, one of them depicting the prophet with a bomb hidden in his turban. The cartoons led to deadly riots in the Muslim world, including in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Film has similarly touched a nerve among Islamic terrorists. Dutch director/producer Theo van Gogh was murdered in 2004 after working with Somali-born writer and politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali on the short film Submission (2004), which took issue with what it characterized as Islamic misogyny.

Artists have been murdered, but seldom for their work. Some avant-garde practitioners were sent to Nazi concentration camps, such as Stefan Filipkiewicz (1879-1944), a progressive Polish painter, and “degenerate artist” Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler (1899-1940). (Wikipedia’s murdered artists category lists painters and photographers murdered in robberies or by lovers and family members. Even so, it’s a short list.)

Activist artists are, of course, no strangers to persecution. Tania Bruguera was recently briefly jailed by the Cuban government after attempting to stage an artwork in which members of the public could speak out on whatever issue they chose. (See How Tania Bruguera’s Whisper Became the Performance Heard Round the World.) Also imprisoned, in this case for much longer, was Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei, though his detention was arguably less a result of his artworks than of his outspoken criticism of the Chinese government.

It’s more often musicians (Pussy Riot, Fela Kuti), filmmakers (Jafar Pahani, Dhondup Wangchen) and writers (Aron Atabek, Ayat Al-Gormezi) who come under the heels of repressive governments.

Even the most high-profile of the recent cases of outrage in the Western world over works of art haven’t inspired physical attacks.

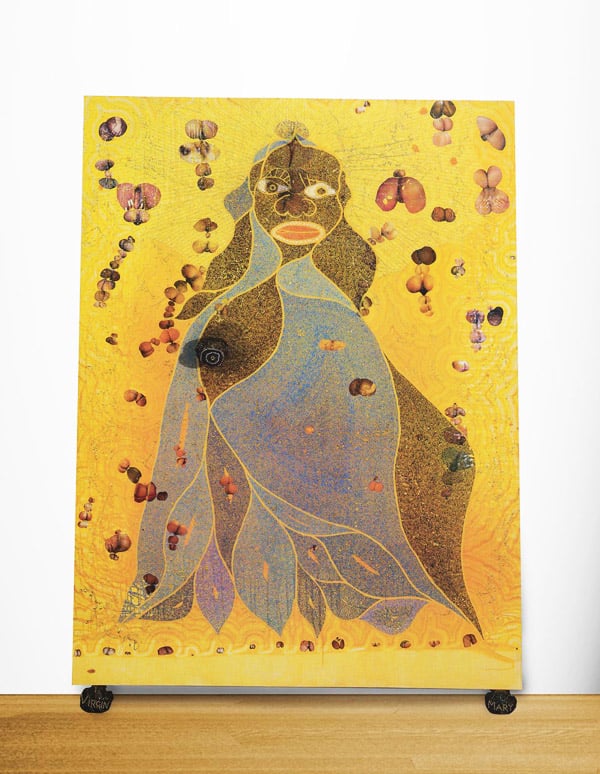

Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary (1996), a depiction of a black mother of Christ adorned with elephant dung and a collage of clips from pornographic magazines, caused picketing by Christian demonstrators when it went on view at the Brooklyn Museum in 1999. Body count: zero.

Chris Ofili, Holy Virgin Mary (1996).

Photo: Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery

Christians were outraged at Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1989), which shows a crucifix immersed in the artist’s own urine. (Never mind that the work was Serrano’s way of commenting on the debasement of his own religion; perhaps it was a bit too nuanced for the masses.) The work continues to anger Christians, as recently as this year (see Christians Pissed about Piss Christ, Again). In any event, the casualty count to date over this work is nil.

A Fire in My Belly, a 1986-87 video showing a crucifix swarming with ants by David Wojnarowicz, raised hackles among Christians and Congressmen when it went on view at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., in 2010. Wojnarowicz had tragically died of AIDS years before. But in this case, the museum directors and curators mercifully had no reason to fear for their lives.

(For more provocative depictions of Christ, check out See the Most Controversial Depictions of Jesus in Art.)

Not that we want artists to be murdered. But the stark contrast makes one wonder about the differences between cartoons and art. Cartoons are immediate, easily legible, and often created for the sake of provocation. Art is often intended to provide a slower burn, offering as many questions as answers.

Cartoonists know they’re in the crosshairs; the Cartoonists Rights Network International monitors cases where cartoonists come under fire, as the Detroit Free Press notes in an article today.

“Cartoons are very reductionist, and despots are also very reductionist, Jack Ohman, editorial cartoonist for the Sacramento Bee and president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, tells the Detroit Free Press. “So therefore, they understand the power of cartoons. Cartoonists are excellent at distillation; they provoke in a way that’s easy to understand … and that’s why they’re feared.”