Art World

Hollywood’s Secret Art Forgery Operation

From Pollock replicas to faux Vermeers, how to get convincing art for your art movie.

From Pollock replicas to faux Vermeers, how to get convincing art for your art movie.

Sarah Cascone

George Clooney, John Goodman and Jean Dujardin on the set of The Monuments Men (2014). Photo: Claudette Barius, courtesy Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. and Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

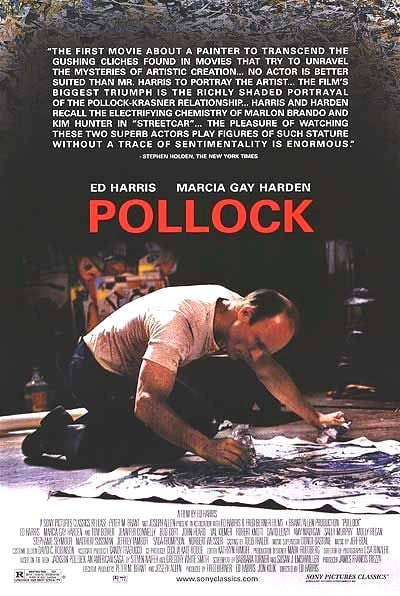

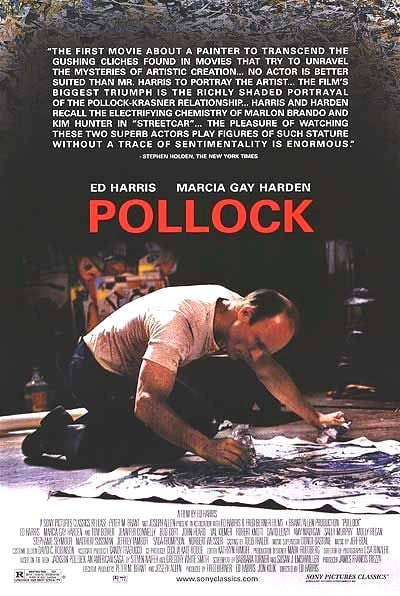

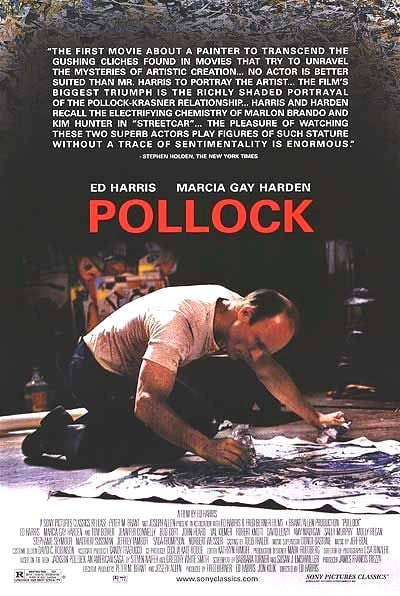

Artists and artwork often make for compelling movie fodder, but getting the rights to reproduce famous paintings can be a real challenge for filmmakers, reports Vanity Fair. A small but strictly-regulated cottage industry of legal art forgery has sprung up on the sets of films by Julian Schnabel, George Clooney, and Ed Harris, among others.

Including artwork in movies has become more complicated since the 1990s, when Lebbeus Woods sued Terry Gilliam, whose 1996 film, 12 Monkeys, featured three major scenes in which star Bruce Willis is brutally interrogated in a futuristic room blatantly copied from Wood’s drawing Neomechanical Tower (Upper) Chamber. The court ruled in favor of Woods; two years later, Warner Brothers had to substantially edit The Devil’s Advocate after the Washington National Cathedral objected to the film’s demonic and sexual portrayal of a replica of its Frederick Hart-designed facade kept in Al Pacino’s office.

Still from Basquiat (1996) by Julian Schnabel.

Now, studios are careful to protect themselves, working with artists and their estates every step of the way. In Schnabel’s 1996 movie about the career of Jean-Michel Basquiat, the high cost of reproduction rights meant that no real paintings by the artists were depicted. Instead, Schnabel and his team created artwork that matched his style of painting. An attorney had the power to reject any pieces that were deemed too similar to a specific Basquiat original.

Some of the other artworks in the movie were real pieces from the director’s personal collection, including Andy Warhol screenprints, and Schnabel’s own paintings standing in as the work of Gary Oldman’s character. The film also included a carefully executed copy of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica. Essentially a giant forgery, the Picasso estate demanded video documentation of the replica’s destruction before they would grant permission.

Detail of Johannes Vermeer, Het meisje met de parel (Girl with a Pearl Earring) (circa 1665).

The Mauritshuis, via Wikimedia Commons.

The production team for Girl with a Pearl Earring, which included some 75 period paintings, attempted to outsource some of their production work to China (see this morning’s Essentials for an item on Chinese factory workers painting replicas of Western masterworks), but were less than pleased with the results.

“They re-painted her to not have the expression, kind of the drunk look, and they kind of orientalized her face,” set designer Todd van Hulzen told Vanity Fair. “And then in another one they even added nail polish to the girl in the painting! And they didn’t get the perspectives right.”

Ultimately, the crew was able to use real footage of the movie’s titular work, Vermeer ‘s best-known painting, thanks to permission granted by the Mauritshuis Museum. As for the other 74, van Hulzen came up with a clever facsimile, adding a reasonably convincing texture to digital printouts by gluing them onto canvas and resurfacing them with a specialized shellac.

Other films, such as Harris’s Pollock, opted to recreate Jackson Pollock’s work by hand, using the famed drip technique to paint over 125 pieces. “It was sort of a miracle, the way they were able to capture the essence and the colors of the existing drip paintings,” Alexandra Tager, the movie’s fine art coordinator, told Vanity Fair. “There was no attempt to copy color for color, drip for drip.”

As for the most recent art blockbuster, Clooney’s The Monuments Men, the production team generally relied on digital technology and 3D-printing to create warehouses full of stolen fine art and the major set pieces like the Ghent Altarpiece. Although scientific advances may have saved time overall, the team still ran into difficulties, as the modern materials sometimes had a chemical reaction to paints and glazes used to add the patina of antiquity.