Politics

Why Self-Censorship of Controversial Artwork is Wrong

Art always offends somebody, and we need to deal with that.

Art always offends somebody, and we need to deal with that.

JJ Charlesworth

Following the shocking events of the massacres and sieges in Paris, a debate has raged over whether or not to publish images of the prophet Muhammad for fear of reprisals, apparently from whichever shadowy fundamentalists might be out there.

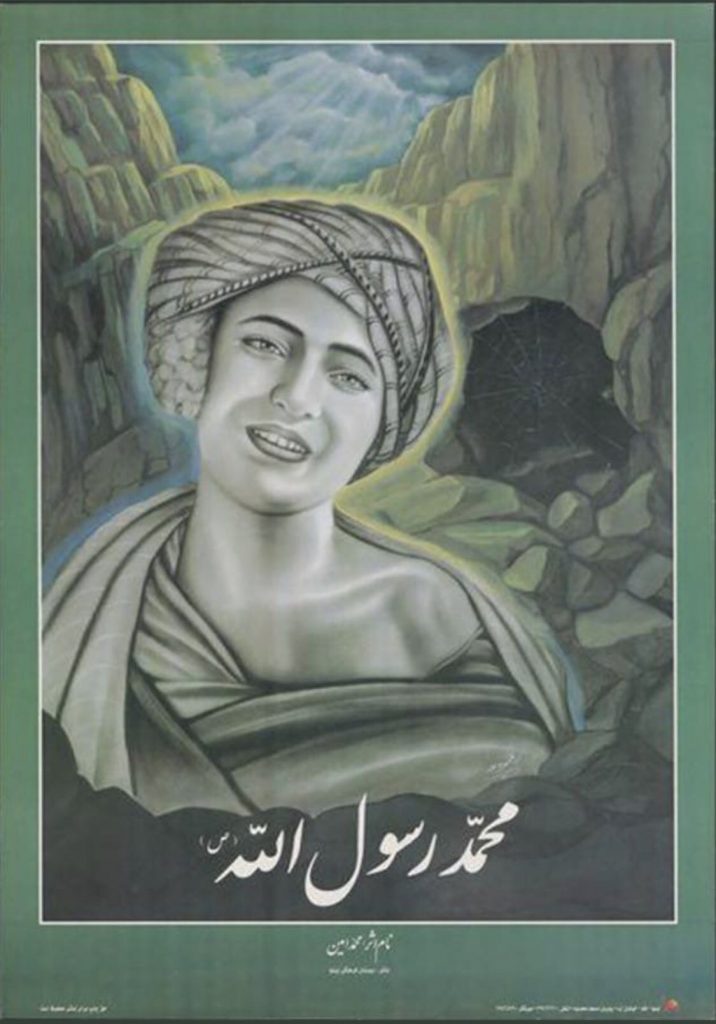

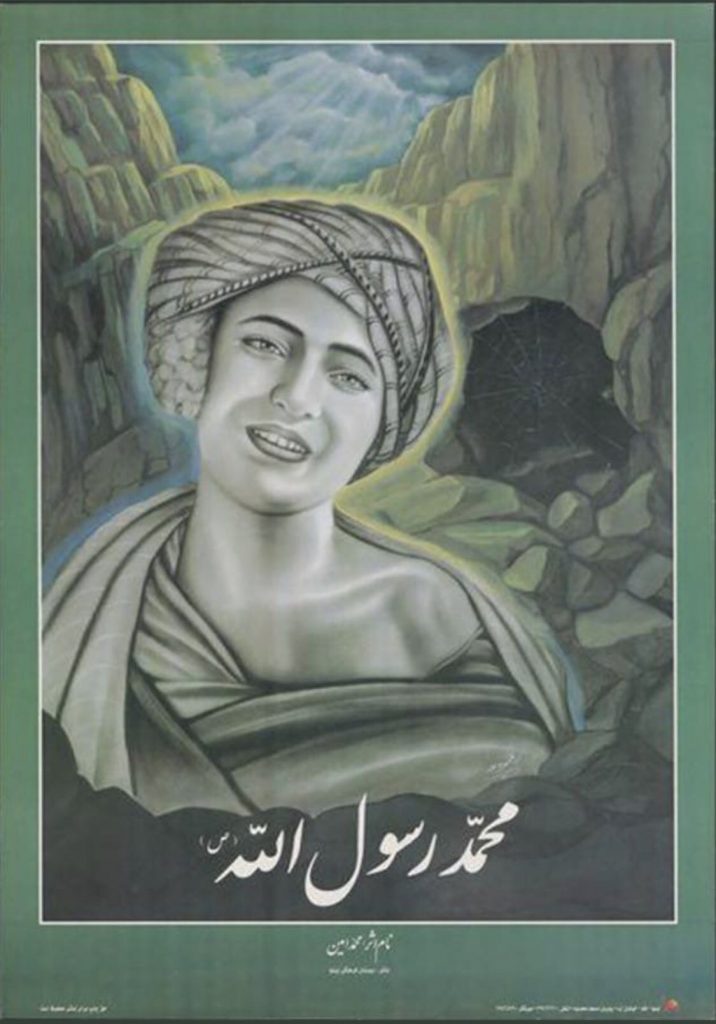

So, the latest news, that London’s Victoria & Albert Museum quietly pulled from its website a reproduction of a 1990 Iranian poster depicting Muhammad, held in the V&A’s collection, is dispiriting. Citing the level of “security alert” the V&A has to operate under, a spokeswoman defended that the work, “as with most of our reserve collections, would be made available to scholars and researchers by appointment.”

The fractious discussion that has arisen on the subject of whether or not media organizations pulling or refusing to publish supposedly blasphemous images are “chicken” has generated more heat than light in the last few weeks; and revelations about how art museums put images on display is only going to provoke similar revelations in the future and put museum staff even more on their guard.

But while we desperately need an open debate about free speech and the freedom to offend in our society, the obsessive focus on Muslims, religion, and blasphemy has diverted attention away from the bigger question of how we handle offending and being offended as part of a big, broad society where not everyone is going to agree.

And that that takes us right into the question of how many parts of society have become hyper-ready to be offended at every expression that crosses a line for them. It also exposes how the idea of what it means to live as part of a “general public” has been confused, and presses at the real meaning of tolerance.

In an interesting blog post for the Guardian, Lois Keidan (head of London’s Live Art Development Agency) reports how, due to the increasing use of social media, she increasingly receives messages of outrage from people who have unwittingly attended live art events whose content they subsequently found upsetting, traumatic, or offensive.

Noting that one of these was “an evening of queer body art,” Keidan argues that all the events in question “were under the radar, artist-run, and aimed at specific ‘communities of interest.’ ”

Yet those offended assumed that, while they had attended an event aimed at a particular “community of interest” they may not have shared, their own sensitivities trumped those of the rest of the audience and the artists. Keidan concludes that today many people “feel entitled, not just to enter spaces and places where they do not necessarily belong, but also to demand censure and closure if they don’t like what they find there.”

Keidan makes the fair point that not all art is made with everybody in mind, but by and for particular groups. It’s also fair to ask that if you turn up as a member of the public, you accept that you might not encounter artworks that totally fit your worldview. And, yet, Keidan’s point of view only really works if one assumes that every artwork should only be seen by those “attuned to it,” those who are part of its “community of interest.” And the trouble with that is that to demand such “safe spaces” for “underground culture,” as Keidan does, eventually means shutting the whole of our cultural life into little boxes marked “niche interest,” in which different groups get to make culture as if nobody else mattered. And the flipside of this is often that, when particular groups decide that they’re entitled to make art for themselves, nobody else has the right to express any view that is critical of their own position or self-identity.

But boxing up art and culture to suit each and every “community of interest,” safely shutting it away so it offends nobody on the “outside,” becomes the easiest response in any time where it appears no one can agree about anything, and in which the first reaction is to shut people up or shut artworks down.

And—coming back to Charlie Hebdo—where might fundamentalists get the idea that you can shut down those public expressions you don’t find palatable? Maybe one should look no further than our “liberal” culture, in which regardless of whether it’s topless models in a tabloid newspaper, or tableaux-vivants in an art gallery, the response everyone seems all too happy to reach for is “shut that down, I’m offended!”

Maybe we are offended. It happens. Public life is not always a pleasant place to be. We should discuss, argue, criticize. But “shut it down”? Before we know it, everything we want to say, every artwork we want to present, will find itself shut up in a box, a sign on the door marked “by appointment only to the appropriate community of interest.”

Maybe we could start by taking back the ideal of tolerance that makes public life livable; that we acknowledge one another’s differences, that we’re not always going to agree, that we’re going to find certain opinions and expressions hurtful; and that this is better than being confined to a cell. That it would be better, as that great American phrase would have it, that we “deal with it.”

JJ Charlesworth is a freelance critic and associate editor at ArtReview magazine. In September artnet News published his article Exhibit B Might Be Offensive To Some But That’s No Reason to Close It Down. Follow @jjcharlesworth on Twitter.