Analysis

The Old Masters Market Is Restoring Its Image to Make It Sexy

Will Old Masters be lonely without some cool downtown company?

Will Old Masters be lonely without some cool downtown company?

Robert Simon

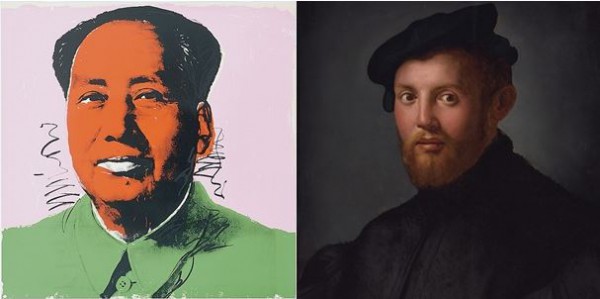

Andy Warhol’s Mao Tse-Tung (1972) (left); Detail of Agnolo Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Book (1525-27) (right).

This week New York becomes the center of the Old Master painting world, with Christie’s and Sotheby’s holding back-to-back sales. This year’s season brings a new initiative to introduce some of the spontaneity and explosive energy of the contemporary art scene to this quiet corner of the art market. Certainly the Old Master field deserves greater attention from collectors, but it is a challenging one for many and mysterious and forbidding one for most. Questions abound of attribution, condition, and provenance, both historic and recent, and determining the value of any single picture is complicated by a host of shifting criteria: the date of the work within an artist’s career, the decorative appeal of its subject (or its absence), the historical importance of the artist, and so on.

How then “to grow” the staid market for Old Master paintings? The answer, it would seem, is to bring some of the excitement, vigor, and money of the contemporary art market to the stolid world of old European paintings. Especially the money.

There have always been “cross-over” collectors, those active across different fields, and today’s are being celebrated as heroes and paradigms. Christie’s website currently features three videos of owners discussing the pleasures of alternating Old Master and contemporary works in their homes. Also on the site is an article with a collector describing how his Pontormo portrait “faces down the gallery and looks at a 1975 de Kooning. I think they really speak to each other,” he says. (Imagine that conversation!) Across town at Sotheby’s, a video shows dealer Fabrizio Moretti exhorting the new collector to hang early Italian religious panels alongside twentieth century minimalists: “I can see a gold ground with a Rothko, a Fontana, a Castellani!” We are not just being given permission to expand our notions of domestic decoration. It seems as if all those old paintings will be lonely without some cool downtown company.

But buying the Old Masters to go with the modern works requires time, study, and awareness of the issues raised above, which is why the Old Master market remains fairly static—populated by a relatively small band of dedicated collectors who analyze a potential purchase with the intensity of playing a match of championship chess. To them, buying a contemporary work is about as demanding as a game of tic-tac-toe.

How then do you entice the tic-tac-toe crowd—who know little about the period, and probably don’t care to learn about it—to make the jump and raise the paddle? The latest effort seems to be by insinuating familiar contemporary references into the arcane world of the Old Masters: what better way to make the neophyte comfortable than to show that the lion can lie down with the lamb, that Pontormo talks to de Kooning, and that we are all equal in artistic paradise?

Consider the catalogue of the current Christie’s Renaissance sale. Among the paintings on offer is an exquisite still-life of a vase of flowers by the German Renaissance painter Ludger Tom Ring the Younger—a name familiar to specialists, though rather obscure outside the field, and surely a mystery to the target collector in one of today’s “emerging markets.” The picture is one of the earliest independent works in the genre and its history and symbolism are intelligently explored in the catalogue entry, but that is clearly not enough to tempt the new buyer. For that, Christie’s has resorted to including a half-page illustration of a Jeff Koons Vase of flowers, described as “strongly reminiscent” of the Renaissance still-life . Similarly, to lure a new collector to an infernal scene by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch, we are proffered a photograph by “Chinese contemporary artist Miao Xiaochun [who] reinterprets Bosch with the most cutting edge medium of our time: computer graphics.”

Perhaps most blatant and irrelevant (and offensive) are the analogies carted out to supplement the impressive Portrait of a Young Man with a Book by Agnolo Bronzino. As a preface to the erudite entry on the painting by scholar Carlo Falciani, we are treated to a bizarre mash-up of the history of portraiture starring Cindy Sherman, Joseph Cornell, Lucian Freud, and Andy Warhol. Somehow they are all being presented as coequals of Bronzino, if not tacitly superior to him due to their contemporaneity. Warhol’s Mao (illustrated) is presented as a counterpart to the Bronzino portrait, echoing “Bronzino’s fascination with power and fashion”— neither quality, it might be noted, being especially evident in the painting being auctioned. The catalogue dutifully informs us that “Although there is no evidence of any knowledge of his work, there is a parallel between the portraiture of Bronzino and that of Andy Warhol, the most celebrated purveyor of ‘iconic’ images of the 20th century.”

Yes, there are of course parallels, just as we might all look identical to a Martian first visiting Earth. But attempting to validate established Old Master painters through specious associations with the darlings of the contemporary market lowers the credibility of the auction house and weakens the authority they have successfully promoted for themselves over the past few decades. And for many who love the art of the period, it lessens the significance of the works being offered, reducing these often complex paintings to simple cognates of their more celebrated contemporary descendants.

In recent years museums have invigorated the appreciation of Old Master paintings through enlightened installations and inspired exhibitions. In New York we’ve been blessed by focus and masterpiece exhibitions at the Frick Collection and grand thematic presentations at the Metropolitan Museum (such as “Renaissance Portraits” and “Art and Love in Renaissance Italy”).

Auction houses, of course, are not in the business of education, but in that of selling art. However, with their new approach to finding new buyers they risk alienating their core audience and trivializing the art they hope to sell.