Galleries

When Is Artist-on-Artist Theft Okay? Jamian Juliano-Villani and Scott Teplin Duke it Out

As per Jamian Juliano-Villani, “Everything is a reference."

As per Jamian Juliano-Villani, “Everything is a reference."

Brian Boucher

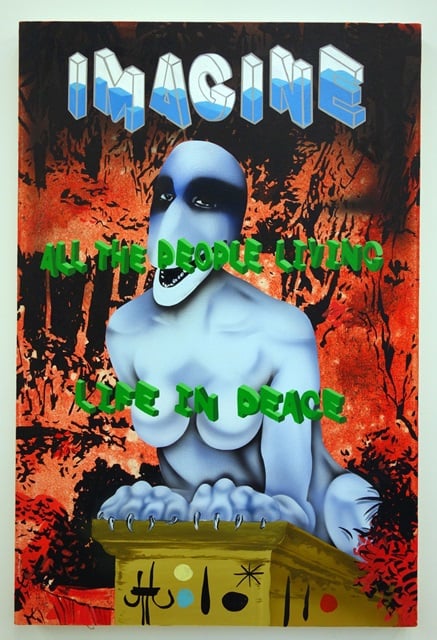

New York artist Jamian Juliano-Villani is being accused by another artist of having sticky fingers. Brooklyn’s Scott Teplin sees too much similarity between a small painting by Juliano-Villani, now on view at West Village gallery Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, and a painting of his own.

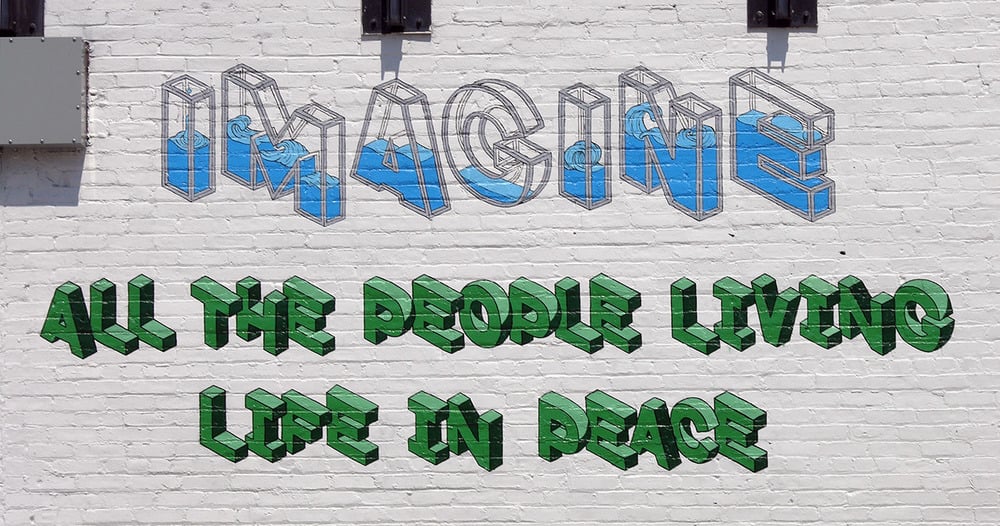

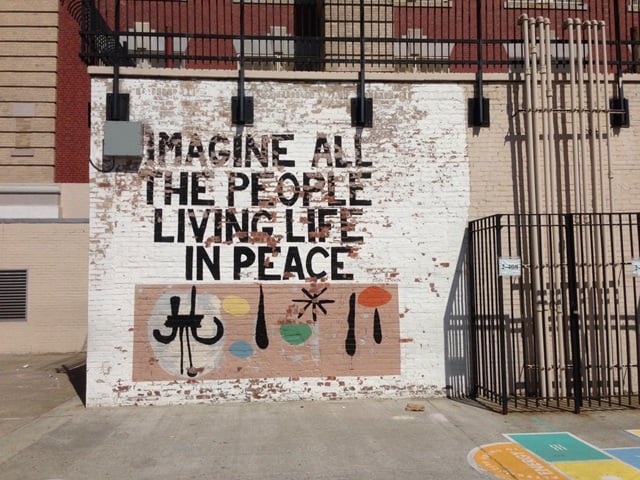

It all started with a peeling mural on the wall of Brooklyn public school PS130, which Teplin’s kids attend. Quoting John Lennon in block letters above some Miró-like abstract shapes, the mural read, “Imagine all the people living life in peace.” Teplin repainted the text in 2013 with 3D-modeled letters, some of which are painted to look as though they were made from glass and partly filled with water. (The original mural was painted by the school’s art teacher, Gerry Moorhead, who was once included in a Metro Pictures group show. Teplin left the Miróesque section untouched.)

Juliano-Villani Instagrammed a picture of the mural a few weeks ago, without identifying Teplin. Soon after, she posted an image of a detail of her own painting, Animal Proverb, which shows a busty, sphinx-like creature sitting atop a plinth decorated with the Miró-like iconography, above which are the John Lennon lyrics mentioned above in block lettering half-filled with water in the style of Teplin’s mural. This is where Teplin drew the line, claiming the lettering was lifted from his own work.

“Everything is a reference,” Juliano-Villani told artnet News in a phone interview. “Everything is sourced.”

“It’s a fucking John Lennon lyric,” she said several times. When we pointed out that Teplin, for his part, is claiming ownership of his lettering, not the lyric, Juliano-Villani repeated, “But it’s a fucking John Lennon lyric.”

Scott Teplin’s mural at Brooklyn school PS130.

The debate came to life last week, when Teplin was tagged in a comment on the mural photo by L.A. artist Russell Etchen, asking if it was Teplin’s. He acknowledged that he had painted the mural and offered a link to a site documenting its creation.

Then began the sniping.

Juliano-Villani shot back, “I guess we should tag john Lennon and give him credit?”

“I was paid nothing,” Teplin retorted. “How much of the $12,000 that Gavin Brown sold your painting for are you planning on giving to PS 130? The PTA could really use it.” (The gallery told artnet News that “that’s the retail price for the painting” but declined to specify whether it sold. Brown also declined to comment.)

“What about the typeface you used in the mural?” Juliano-Villani asked. “Do those designers get credit?”

Teplin asserts in a page on his website that he’s been working on the water-filled lettering since 1999.

Juliano-Villani explained her thinking in a Facebook comment:

It’s important to realize that all visual culture is fair game for artistic content, ‘appropriation’ isn’t a ‘kind’ of work, it’s almost all art. When making a painting or a print or a sculpture, it’s nearly impossible to make something without thinking of something else. A good reminder that when dealing with images 1) once an image is used, it isn’t dead. it can be recontextualized, redistributed, reimagined. 2) It should have several lives and exist in different scenarios.

The lettering in Teplin’s mural.

Newark-born Juliano-Villani, 28, was recently featured in Forbes‘s “30 Under 30” (see Which Artists Made Forbes’ 30 Under 30 List?). Her work was also showcased in the inaugural exhibition at Zach Feuer and Joel Mesler’s Retrospective gallery, in Hudson, New York.

L.A. art collector, dealer and advisor Stefan Simchowitz has taken an interest. “I like her a lot,” he told artnet News by email (see Christopher Glazek Annotates His NYT Stefan Simchowitz Story). New York Times critic Roberta Smith, writing about the Gavin Brown show, referred to the young painter as one of the “unfamiliar names [that] impress.”

Her trippy acrylic paintings combine cartoonish imagery from far-flung sources, some of them actual cartoons from artists like Chuck Jones. She calls her use of other artists’ work “simultaneous exploitation and homage.” She mashes up a bicycle wheel with some fish out of water against the backdrop of a barnyard in Russell’s Corner, 2014, which will be included in her first museum solo, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, opening February 6.

Teplin is 42, and his works reside in the collections of the New Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Walker Art Center and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others. Since his first gallery solo, at Seattle’s Howard House in 1999, he’s had solos with Adam Baumgold Gallery (New York), g-module (Paris), and Ryan/Lee Gallery, New York, which now represents him. (For the record, I own a Teplin drawing, which I received as a gift from a friend several years ago.)

Juliano-Villani then posted a photo of her own painting on Facebook, crediting Teplin in the comments and offering a link to his website.

Funny enough, it’s not the first time Teplin has been robbed, as it were. In 2013, Brooklyn artist-curator Adam Parker Smith mounted a group show at New York’s Lu Magnus Gallery with objects he stole from other artists during studio visits. (I wrote about the show for Art in America’s website.)

Picasso is supposed to have said that good artists borrow, while great artists steal, and in our phone conversation with the artist, Juliano-Villani stood by the belief that pretty much everything is in the public domain. Artists like Jeff Koons and Richard Prince, who have lost or settled high-stakes copyright cases, might see it otherwise.

Teplin’s mural is especially free for the taking, Juliano-Villani said, since it is outdoors.

This is hardly a David vs. Goliath story, like a postcard maker suing Jeff Koons, as happened with his sculpture String of Puppies (for the latest copyright infringement suit against Koons, see Jeff Koons Sued for Plagiarism) or Richard Prince taking imagery from photographer Patrick Cariou (see Patrick Cariou Drops Copyright Lawsuit Against Richard Prince). Twelve thousand bucks is hardly the tens of millions that Prince’s Canal Zone paintings are reported to have fetched, and the case is unlikely to go to court any time soon.

But the row highlights the varying takes on what’s proper by artists of different generations, and pits an artist on the rise against an artist who’s been in the trenches for well over a decade.

The mural, painted by Gerry Moorhead, before Teplin repainted it.

“I like some appropriation art,” Teplin told artnet News via phone. “I don’t do it myself. But where do you draw the line? I don’t want money from her. But this feels bad.”