Photo © Photograph: Ramin Talaie/Getty.

Eileen Kinsella

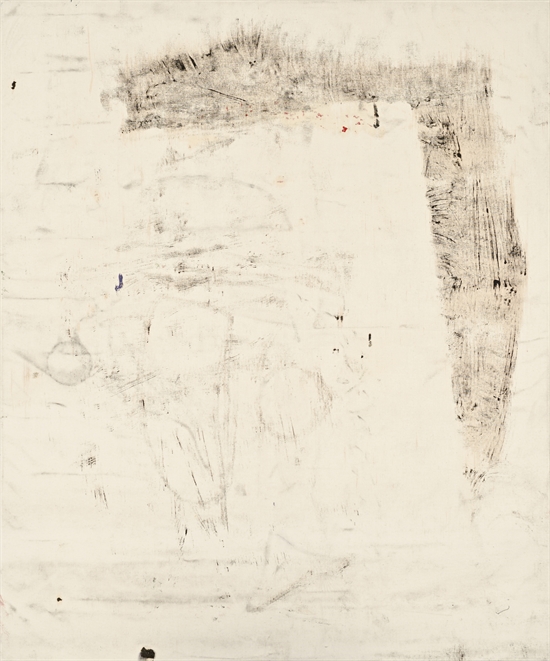

Joe Bradley’s Untitled (2012) sold for $330,000 on artnet Auctions.

It has been another year of superlatives in the art world, with fairs around the world reporting record attendance and robust sales, and top auction houses taking in hundreds of millions each season.

More and more, individual lots are selling above $10 million—even $20 million—as evidenced in the New York November sales. In the first two weeks of November alone, the total at Christie’s for Impressionist, modern, postwar, and contemporary sales was a whopping $1.16 billion, of which the bulk, or $852.9 million, was realized for its single evening sale of contemporary art on November 12. The grand total at Sotheby’s was $1.02 billion.

However, recent news of the resignations of Sotheby’s CEO Bill Ruprecht and Christie’s CEO Steven Murphy (whose departure was even more sudden than Ruprecht’s) have prompted many questions and closer analysis of just how profitable those headline-grabbing sales are. In one recent report, Christie’s worldwide head of contemporary art, Brett Gorvy, said that profit margins on major contemporary sales rarely exceed 8 percent. (See “Sotheby’s CEO Ruprecht Pushed Out” and “Why Was Christie’s CEO Steven Murphy Fired?“)

Meanwhile, the global boom and vibrant demand for contemporary art is extending to price points under $100,000, further fueled by a new generation of younger buyers at ease with making such purchases online.

Roxanna Zarnegar, senior vice president of auctions and private sales at Artnet Worldwide, artnet News’ parent company, said: “Our sell-through rates over the last three years have doubled. Our volume has gone down but our value and price points have gone up double.”

Zarnegar said that at the start of the year, prices of individual lots sold in artnet Auctions were running about $5,000 to $15,000 but have since increased to about $10,000 to $100,000. That price point she says, “covers a very exciting Gen Y demographic that the brick and mortar can’t seem to get their heads around.”

In addition to a burst of energy from new buyers in Latin America focusing on contemporary art—particularly in Brazil and, more recently, Argentina—she says, “China now has graduated from the term ’emerging’ and is really a blue chip country.” And though she does think a correction, or downturn in the market, is inevitable, she adds that at some point, “I don’t think that it’s going to be a dramatic as it was several years ago. I think it’s going to level off because there are new and different ways to buy art.”

Richard Prince’s Untitled (1992) (from his “Cowboys and Girlfriends” series) sold for $71,760 on artnet Auctions.

Photo: Courtesy artnet.

Zarnegar points out that educating collectors has been an integral part of artnet auctions’ success in attracting and keeping new buyers. “I think the thing about artnet Auctions is that it’s tied into collectors learning more before they raise their paddle, whether it’s a virtual paddle or not,” she says. “The connection artnet Auctions has to the price database and the gallery network—that whole suite of products that’s evolving for us—is a way to keep people in the know, which could balance any sort of a correction.”

The artnet Price Database has over eight million color-illustrated auction records, with auction house sales results dating to 1985, from more than 1,600 auction houses and over 300,000 artists. Zarnegar says, “We’re openly saying ‘This is our number one product.’ The price database is our number one differentiation point in terms of the transparency and the trust that we’ve built with collectors. We’re teaching them how to buy art in such a way that could withstand a major market downturn.”

Illustrating the strength that artnet Auctions has carved out in this particular niche, the top lots of 2014 include Joe Bradley’s Untitled (2012), which sold in an online auction to a US buyer for $330,000, followed by Yayoi Kusama’s Stars (2012), which brought $297,000 from a bidder in London.

Among top post-sale results was Fernando Botero’s Cavallino (2001), which brought in $220,000, and Richard Prince’s Untitled (1992) (from the series “Cowboys and Girlfriends“), which sold for $71,760.