Politics

‘Nobody Could Remain Silent’: The Killing of an Artist and Activist in Belarus Has Added Fuel to Widespread Protests Against the Government

The country's president was recently re-elected in a widely disputed election.

The country's president was recently re-elected in a widely disputed election.

Kate Brown &

Naomi Rea

Human rights organizations are sounding the alarm in Belarus amid the country’s harsh crackdown on protesters following the disputed re-election of president Aleksandr G. Lukashenko.

Artists, including one who was killed by what are believed to have been police forces last month, are among those on the front lines, and are being persecuted for using their work to speak out against an increasingly authoritarian regime.

Thousands of people, including dozens of artists, have been arrested for supporting the protests since August 9, the day Lukashenko was re-elected in proceedings deemed by the Council of Europe to be “neither free nor fair.”

In June, the human rights organization Our House reported at least 73 cases of artists who had been persecuted for their activism; identified at least nine artists being held as political prisoners; and reported that the government had initiated at least 20 criminal cases against activists who had used their art to criticize Lukashenko’s government.

People flash the V-sign to pay tribute to late opposition protester, artist Roman Bondarenko, during his funeral ceremony in Minsk on November 20. Photo: Stringer/AFP via Getty Images.

Meanwhile, Belarusian police have grown increasingly brutal. In November in Minsk, 31-year-old painter and activist Roman Bondarenko was stopped by plainclothes officers during an altercation between opposition and pro-government citizens. Eye witnesses claim to have seen masked men, thought to be police, beating Bondarenko, who later died in hospital.

Though officials have claimed the artist was intoxicated at the time of his arrest, a doctor who treated him has refuted that claim. The doctor is now in police custody, according to German newswire Deutschland Funk.

In rallies following Bondarenko’s death, demonstrators have chanted his final text message as a call to arms: “I’m going out.”

The ongoing protests have been a watershed moment for artists in the country, who for many years self-censored out of fears of persecution, multimedia artist Nadya Sayapina told Artnet News. But after the police violence during the election, the artist said, “nobody could remain silent.”

Sayapina was arrested on August 15 for her participation in a demonstration and performance in Minsk. On October 11, in response to her arrest, more than 700 people signed an open letter calling for “the end of the persecution of cultural workers for their artistic expression,” as well as as a new, free election.

Sayapina has continued to show works that are subtly critical of the government, most recently presenting a series of 11 portraits of women she met while in jail.

I Believe or the Philistine World of Political Animals, Performance by Alexei Kuzmich. Courtesy the artist.

Another artist, Alexei Kuzmich, was arrested following a brazen performance on election day that was critical of the government. At a polling station, the artist undressed and posed as if crucified with his polling card attached to his chest. Soon after, he says, he was tortured while in police custody.

Kuzmich told Artnet News he was forced to leave Belarus for Ukraine in September, after the government fabricated a criminal case against him. He described the current authorities as a “criminal group” that has seized power in Belarus and tried to “suppress any free artistic expression.”

Yet despite the ongoing danger, Kuzmich is among many artists who continue to rally behind the country’s opposition movement.

“Of course, this is dangerous, and you can be deprived of freedom, homeland, or even life. But then why choose the profession of an artist?” he says. “The situation that is happening now in Belarus is a goldmine for self-expression.”

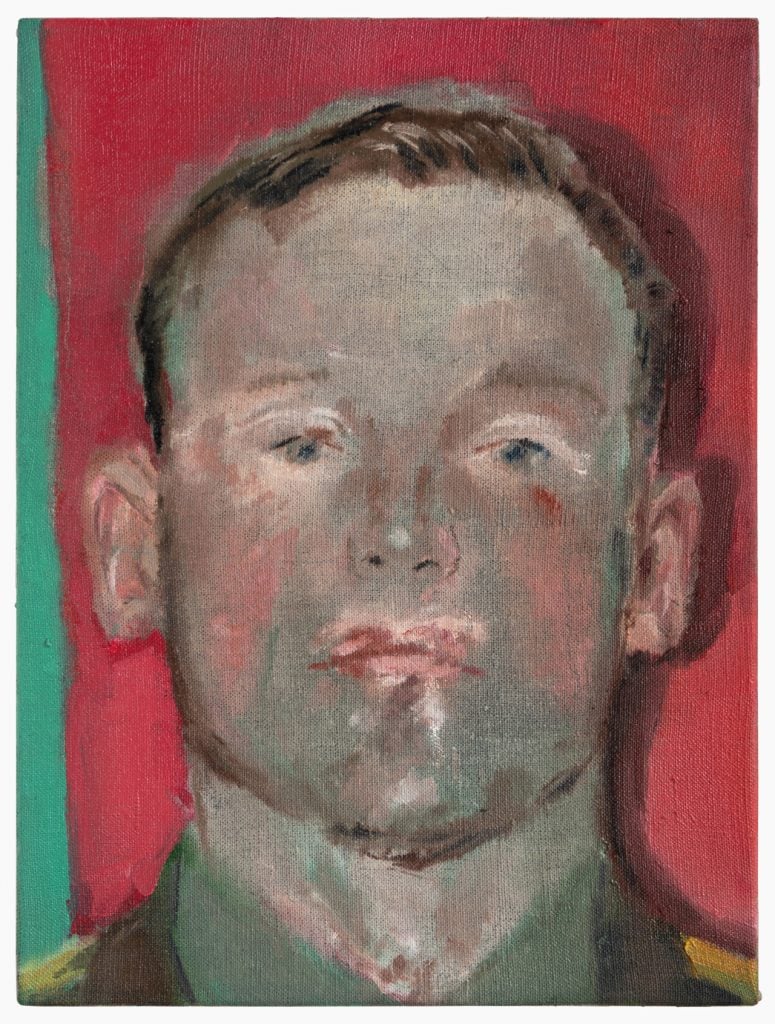

Andrey Arno’s The Young Ideologist from the show “This Silence Speaks Volumes” (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Lukashenko has gradually eroded artistic freedoms since coming to power in 1994. The ex-Soviet nation still has a close relationship with Russia, and has kept many Soviet-style institutions, including a police force named after the K.G.B. and an economy that is largely state run.

To suppress dissent, Lukashenko has fostered a network of spies and informants, called “curators,” who collect information on anyone suspected of “disloyalty.” The systematic detainment and psychological or physical disparagement of dissenters has a long history in the Eastern European nation.

“Artistic freedoms in Belarus were suppressed even before the start of the mass protests, but this was not as noticeable as it is now,” photographer and painter Andrey Anro told Artnet News.

A month before the election, he opened “This Silence Speaks Volumes,” an exhibition that was critical of Lukashenko’s dictatorship while examining patterns across authoritarian regimes. The show went ahead despite fears from the gallery’s owners that they might be closed down, according to Anro, who says that the fraudulent elections have only emboldened him.

“There is no contemporary art museum in Belarus, because it is critical art,” the artist told Artnet News. “Any criticism of the state during the Lukashenko era was always not allowed in state institutions, or it was so veiled that it was not read directly.”