Politics

Can Art Help Heal a Divided Nation? Here Are 6 Ways That Red-State Museums Are Reaching Across the Political Gap

Directors from four museums in conservative states weigh in on strategies for going beyond the art world's "blue bubbles."

Directors from four museums in conservative states weigh in on strategies for going beyond the art world's "blue bubbles."

Rachel Corbett

The so-called “blue wave” in November’s midterm elections returned some congressional power in America to the Democrats. But with Republicans maintaining control of the senate and the presidency, the nation is as sharply divided as ever, largely along geographic lines of rural versus urban, “red states” versus “blue,” coasts versus the center.

Art museums, however, are situated in every state, giving them a special edge in connecting with communities that the coastally-saturated art world usually does not. To find out how museums are bridging this growing chasm, we spoke to directors and curators at four art museums in conservative-leaning states around the country: The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in North Carolina, the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama, the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City.

Although these museums are all situated in university towns, each spoke of their urgent efforts to reach out beyond these “blue bubbles” and draw in communities that haven’t historically found much value in art. Here are a few strategies for how they’re doing it.

Installation view of the 2016 show “Ideologue” at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art.

Many of the issues that get politicized in the public discourse can be framed in non-partisan ways, making it harder to alienate viewers based on their party affiliation.

The Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, for example, is in the midst of a series of exhibitions that examines the consequences of rapid suburban expansion. “Depending on a viewer’s stance about any number of issues from affordable housing, to water usage, to the perception of safety, these could be equated with political issues, but in reality, they are community issues, interconnected, and complex,” says director Kristian Anderson.

If viewers still perceive a political agenda, it may be useful to have written value guidelines in place to provide as a reference. At the Philbrook Museum in Tulsa, one of director Scott Stulen’s first orders of business when he came on board in 2016 was to draft value statements for the museum. “These are the principles that everything we do is guided by: education, creativity, health/wellness, social justice—that was a big accomplishment to get in there but the board voted on it—sustainability, and being a leader and innovator—taking risks.”

Durham artists Joan Yabani (right), an immigrant from Ghana, and Winnie Okwakol, an immigrant from Uganda, designed a jumbo coloring book mural responding to ideas in FDR’s “Four Freedoms” address. Courtesy of the Nasher Museum.

Conservatism looks very different in Birmingham than it does in, say, Salt Lake City or Lubbock, Texas.

In Oklahoma, “it’s kind of a Reagan-era conservatism—a little more libertarian, a little less socially conservative,” Stulen said. “I’ve got members of our audience who wish we were out there protesting in the streets and members who, if we get too political, it would turn them off.” The challenge for his museum is “understanding our audience and finding subjects that everyone in the community can be a part of,” he said. “Things like education. Shouldn’t we all be for education?”

This doesn’t mean museums have to whitewash their programming. After all, there’s often a lot of diversity in red states. “Durham also has a long history of a large, vibrant African American community that today makes up over 40 percent of the population,” says Nasher Museum curator and deputy director Trevor Schoonmaker.

“That cultural foundation and community here has helped us do what we do. For instance, when we opened ‘Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool’ in 2008, I’m sad to say most of the country, including the majority of the contemporary art world, didn’t know who he was. The diverse community here, however, responded overwhelmingly positively to his work right off the bat, despite his name not being familiar.” (Since then, Hendricks has been included in a number of high-profile exhibitions ranging from Prospect.4 in New Orleans to “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” now on view at the Brooklyn Museum.)

Although the museum was “already focused on under-recognized art, artists and cultural histories” well before the 2016 elections, Schoonmaker said the payoff is only now becoming widely apparent: “What may have changed is the broader public is even hungrier for what we’ve been doing. Society feels the urgency.”

Installation view of “Cities of Conviction” at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art.

Last year, the Utah Museum staged an exhibition of contemporary Saudi Arabian art—which might seem unlikely to strike a chord in Salt Lake City’s heavily Mormon community. But the show, titled “Cities of Conviction,” resonated among those in the Church of Latter-day Saints who see themselves as persecuted religious minorities. Besides finding this common ground with some Muslims, the show also drew parallels between Salt Lake City and Saudi holy centers like Medina as sites of pilgrimage.

“When we approach topics that are conservative hot buttons, such as LGBTQ themes, we receive some push back,” Anderson acknowledged. “However, one of the unique areas of Utah’s conservative culture is that, in general, it is very supportive of refugees and immigration in general, and very supportive of interfaith dialogue.”

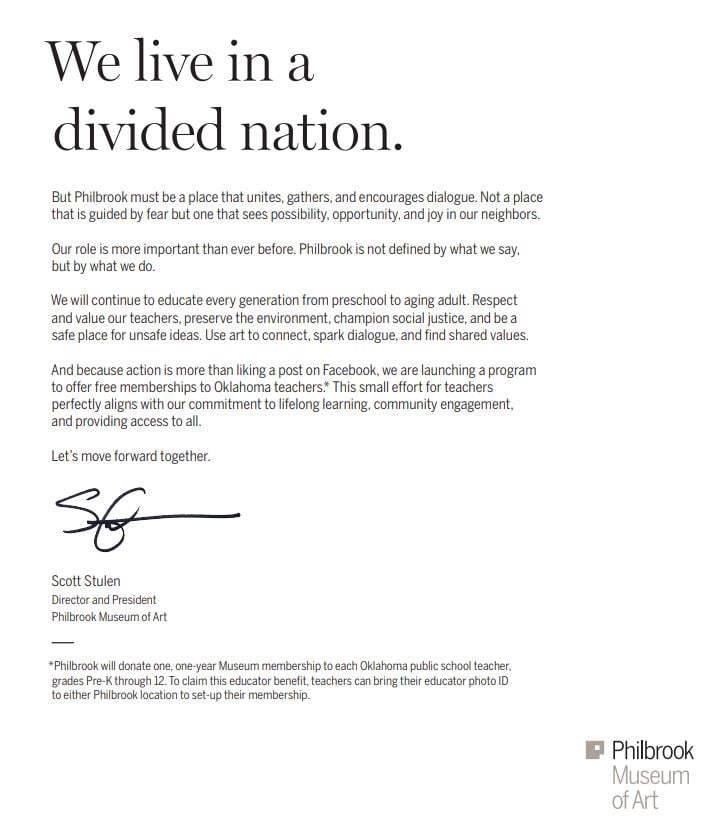

The Philbrook Museum’s full-page ad offering public school teachers free museum membership after Oklahoma denied them a wage increase. Courtesy of the Philbrook.

As part of the Birmingham Museum’s exhibition “For Freedoms: Civil Rights and Human Rights,” which was on view during November’s midterm elections, the institution supplied voter registration forms and a guide about how to cast a ballot for first-time voters.

Similarly, in Tulsa, the Philbrook Museum held an information session on voting issues and the candidates ahead of the midterms. It was a way to be “non-partisan but put information out there,” Stulen said.

The Philbrook took an even more direct response to a local political issue during the 2016 elections: a ballot measure that asked Oklahomans whether to increase salaries for its public school teachers, who are among the lowest-paid in the country. “It was defeated and wasn’t even close,” Stulen said. As a result, the museum took out a full-page ad in the newspaper announcing that all public school teachers would qualify to receive free membership to the museum.

“There was no question about what side we were on, but we’re doing it in a way that was about how we can be actionable and then use that to talk about the importance of education,” Stulen said. Today, the museum has 778 teachers in its membership and has seen a notable uptick in school tours.

The Philbrook’s lowrider picnic.

Museums haven’t historically been the coziest of spaces. But as institutions struggle to reach new audiences, some are finding that hospitality is a good place to start. “When I came in, the [Philbrook] was a cold museum—don’t touch anything, don’t walk on the grass. We got rid of all those restrictions within weeks,” Stulen said. “We put picnic tables all over the campus, created much more welcoming atmosphere, put up more bilingual materials.”

For a Chicano art show last summer with the comedian Cheech Marin, the museum hosted a “lowrider picnic,” with 30 cars jacked up on the lawn. The event, Stulen said, drew 1,200 people.

The Birmingham Museum of Art.

Sometimes there are subtle ways to make a difference. The Philbrook museum once advertised itself as a wedding venue on social media with an image of a same-sex couple. “There actually was not a single issue with that,” Stulen said. “That shows that we’re making progress.”

The museum, like others across the country, is also rearranging its collections in ways that more cohesively incorporate narratives previously alienated from Eurocentric models of art history. Instead of having its large Native American art collection segregated from the European art collections, for example, the museum is now weaving it together to “tell the stories simultaneously,” Stulen said.

The Birmingham Museum has also taken steps to foster a more global vision of its collection. Its two year-long show “Third Space / Shifting Conversations About Contemporary Art,” which included more than 100 works from its collection by artists including Kerry James Marshall, Ebony G. Patterson, Mark Bradford, José Bedia, and Thornton Dial, aimed to create “connections between the American South and other parts of the world using contemporary art organized through a series of themes, including: migration/diaspora/exile, gaze/agency/representation, spirit/nature/landscape, and traditions/histories/memory,” said the museum’s director, Graham Boettcher.

After the show went up, the museum saw an increase in attendance and widespread praise from critics, such as the New York Times‘s Holland Cotter, who named it in his “Best of Art” roundup of 2017.

“Because of our past, I think most Birminghamians strive for unity, no matter what their political conviction,” Boettcher said. “This didn’t begin with the most recent presidential election, and it certainly won’t end with the next.”