Art History

Art Bites: How the Modesty Police Used Fig Leaves to Censor Nudes

The “Fig Leaf Campaign” of the 1500s covered up older sculptures and paintings.

The “Fig Leaf Campaign” of the 1500s covered up older sculptures and paintings.

Verity Babbs

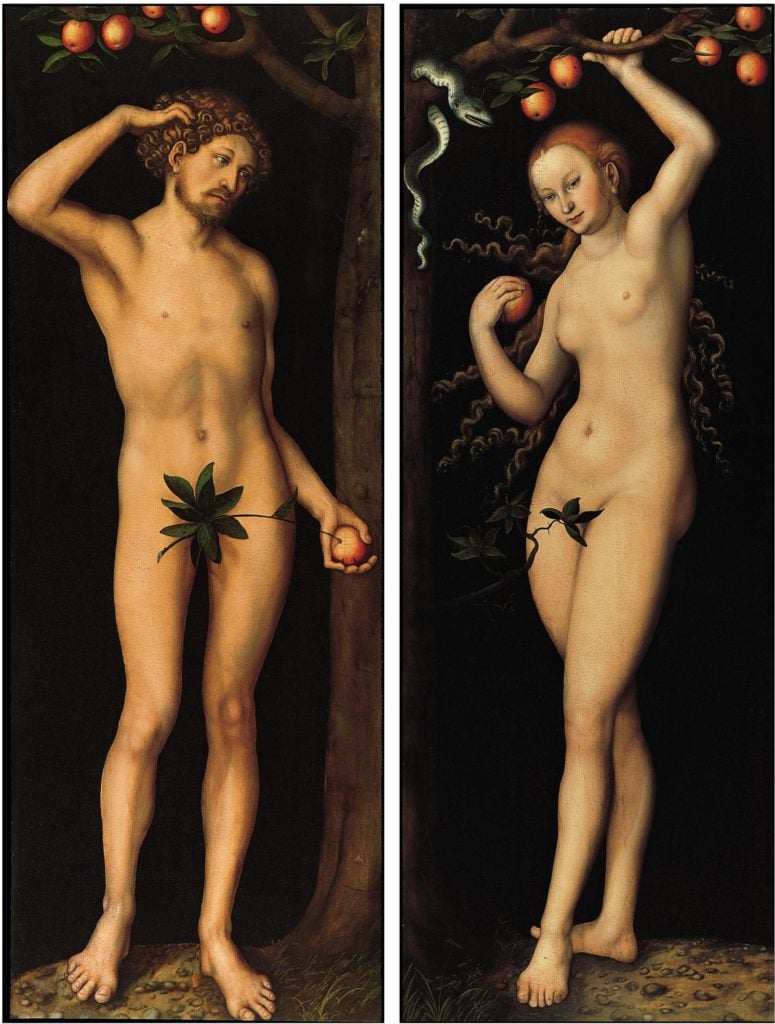

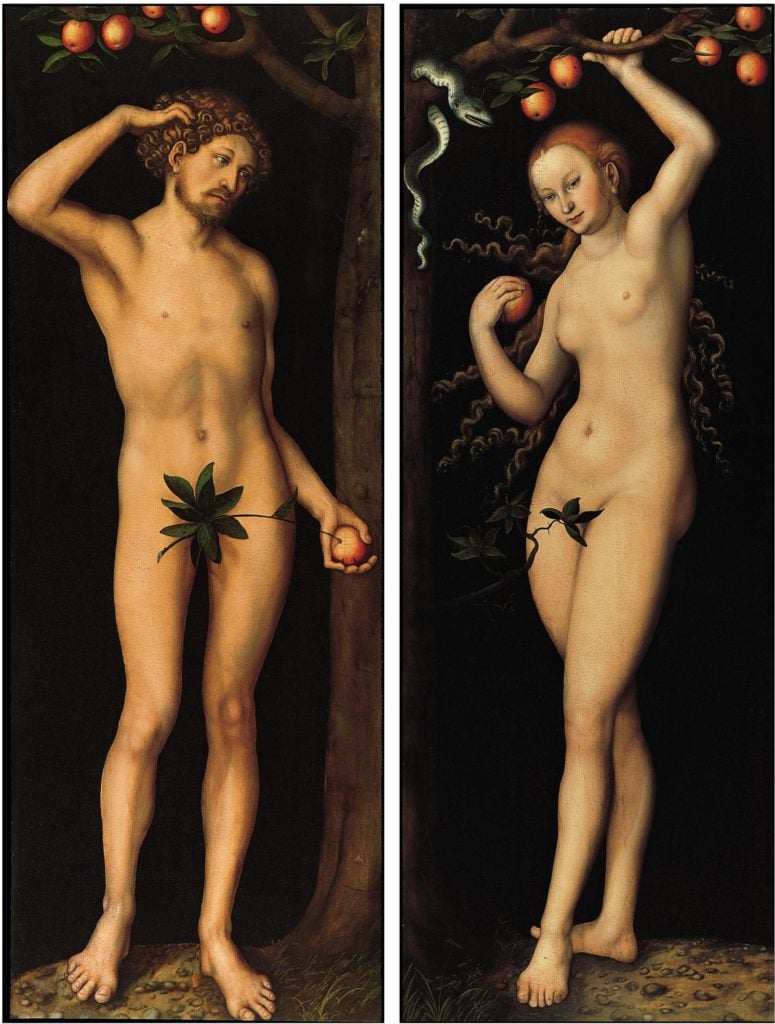

The fig leaf is known as a symbol of modesty in art. The motif drawn was from the Bible, when in Genesis Adam and Eve realized their nakedness after eating the forbidden fruit, and sewed together fig leaves to cover their bodies. However, before the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity in 380 C.E., ancient societies celebrated the naked human form as a symbol of heroism, strength, and beauty.

Christian doctrine around modesty changed attitudes to nudity, and artworks began to be made with nude figures covered up from the 1st century C.E. The Counter-Reformation of the 1500s, which saw a reorganization of the Catholic Church in response to the Protestant Reformation, further emphasized the notion that public displays of nudity were obscene. At this time, figures in art that were still shown fully naked were likely to be sinning or idiotic characters.

Jan van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece (1432). © Sint-Baafskathedraal Gent. Photo: Dominique Provost.

But what do you do with the old artworks that aren’t covered-up? In 1563 the Council of Trent, the ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, put forward new guidance regarding the nudity on display in artworks that adorned places of worship and public spaces. In 1564 the council released a decree that said that “pictures in the Apostolic Chapel should be covered over, and those in other churches should be destroyed, if they display anything that is obscene or clearly false”.

The so-called “Fig Leaf Campaign” saw new fig leaves painted onto pre-existing paintings and cover-ups added to sculptures. Just a couple of decades before, Michelangelo’s Last Judgement (1536-41) on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, caused controversy because the majority of the male figures and angels were nude. According to the 16th-century painter and artist biographer Giorgio Vasari, Pope Paul III’s Master of Ceremonies Biagio de Cesena said that “it was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns”. Many of the nude figures in Michelangelo’s masterpiece were painted over with fabric covers by the artist Daniele da Volterra, following Michelangelo’s death.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgement (1536-41). Image copyright Vatican Museums.

This squeamish attitude to nudity continued for hundreds of years. In 1680 Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1425) was painted over with modesty vines, and in the 19th century Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432) had new panels commissioned to replace the originals of Adam and Eve, swapping them for fully-clothed figures despite the fact the originals already had fig leaves covering them up. In Victorian times a copy of Michelangelo’s David (1501-4) was gifted to Queen Victoria by the Grand Duke of Tuscany, with a leaf added to “spare the blushes of visiting female dignitaries”. The leaf has since been removed but is kept in a nearby display cabinet.