Opinion

Why Facebook Is a Waste of Time—and Money—for Arts Nonprofits

The co-founder of the nonprofit Center for Artistic Activism explains why his company has officially de-friended Facebook.

The co-founder of the nonprofit Center for Artistic Activism explains why his company has officially de-friended Facebook.

Steve Lambert

Like many nonprofits, we use Facebook to connect with our audiences, and they use Facebook to stay in touch with us. It’s not our preferred way, but it’s where more than 4,000 people have chosen to stay informed about what we do at the Center for Artistic Activism. Part of our philosophy at the C4AA is to meet people where they are, and, undeniably, hundreds of millions of people (and some bots) are on Facebook. However, looking at the statistics provided by Facebook, we’ve come to realize that the connection we were after isn’t actually made.

That’s why we’ve decided to stop putting effort into Facebook. The world’s largest social network has become an increasingly inhospitable place for nonprofits.

We currently have 4,093 “fans” of our page on Facebook. For a scrappy organization focused on artistic activism, that’s not bad (especially since we never bought followers to boost our numbers). Those thousands came from years of hard work doing outreach.

From left: Steve Lambert, Rebecca Bray, and Stephen Duncombe, directors of the C4AA. Courtesy of Steve Lambert.

Stephen Duncombe and I started the organization around 2009, shortly after Facebook asked organizations to create “pages” to help differentiate from personal “profiles.” In those early years, we used our fan page to share the progress we were making to support artists and activists fighting corruption in West Africa, to help save lives in the opioid crisis, to get proper healthcare for LGBTQ people in Eastern Europe, and our work to make activism more creative, fun, and effective.

After trainings and other events, our page was especially active as new alumni from countries around the world joined to stay in touch. However, in recent years, the traffic dropped off.

During that time, we’ve grown significantly as an organization—adding staff positions, increasing programming—but I wouldn’t blame our Facebook followers for thinking the C4AA was dormant, if not dead.

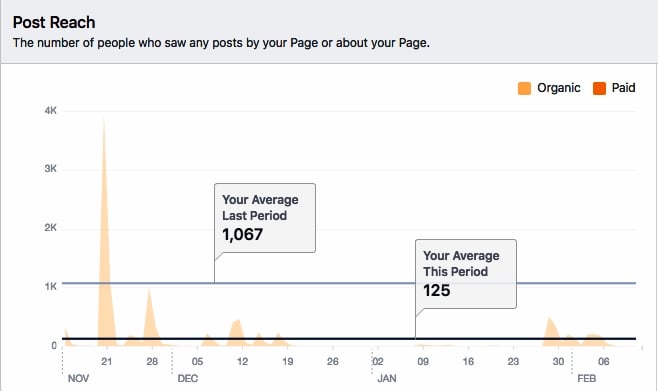

They weren’t seeing everything we shared—and may not have been seeing anything. They’ve asked to hear from us, but Facebook decides if and when they actually do. And in reality, it’s not often. Here are the stats Facebook provides us:

Screenshot of C4AA’s Facebook analytics. Courtesy of Steve Lambert.

This shows how many people (anyone, not exclusively fans of our page) have seen our posts over the past three months. With a few exceptions, you can see most posts don’t reach more than a tenth of the number who have opted to follow our page. In recent weeks, we’ve reached an average of around 3 percent.

This is by design. People think the Facebook algorithm is complicated, and it does weigh many factors, but reaching audiences through their algorithm is driven by one thing above all others: payment. Facebook’s business model for organizations is to sell your audience back to you.

In the past, you could boost your social media reach by writing better posts and including images and video. But in recent years, targeted spending on advertising has overtaken all other tips and tricks. To reach more people who already requested to hear from the C4AA, we’d have to give our donors’ money to Facebook to “boost” our posts.

Now, are we simply against paying Facebook? Do we not want to give our donors’ money to one of the largest corporations on the planet, one that has enriched its leadership and shareholders by not paying the artists, journalists, and everyday people who give the site value? Do we want to withhold support to a company that’s barely taken responsibility for enabling Russian disinformation to reach US citizens in an effort to undermine democratic elections? Do we think that Facebook is turning the internet from an autonomous, social democratic space into an expanding, poorly managed shopping mall featuring a food court of candied garbage and Jumbotrons blasting extreme propaganda that’s built on top of the grave of the free and open web? Yes, yes, yes, and yes. That’s why we’ve never been big fans, much less paid to use Facebook.

However, for the sake of argument, let’s imagine that we accept that this is Facebook’s business model, and it is free to create its own rules on its private platform. Fine. There’s still a broader inequity to address.

Facebook’s pricing treats nonprofits and artists the same as a multinational corporation like Coca-Cola, a high-end neighborhood boutique hair salon, or a vitamin supplement scam. The advertising model makes no exceptions for nonprofits—even though we have nothing to sell and our mission, legally bound, is for the common good.

This difference in purpose is significant. It’s why the US government does not charge taxes to nonprofits, and the postal service offers reduced rates. Even other tech companies put nonprofits in a different category. Paypal charges less to process charitable donations and enables fundraising opportunities through partners like eBay.

At the C4AA, we use the messaging system Slack, and were delighted to learn it offers a significant discount to non-profits to upgrade from their free plan to the standard plan. That discount? 100 percent. To upgrade to the top plan, the Plus Plan, the discount is 85 percent. Slack partners with the non-profit TechSoup, which arranges discounted software, hardware, and support from for-profits to nonprofit organizations. One TechSoup partner, Google—yes, that Google—offers thousands of in-kind dollars for “ad grants” so nonprofits can compete to communicate alongside for-profit companies.

Facebook offers no such discount. It considers all communication from any organization to be a form of “advertising.” Facebook will take the money of anyone who pays—whether to sell products or discord.

Sure, we can keep posting there anyway for free, but less than 3 percent of our followers would know.

Meanwhile, the Facebook-using public—around two billion people—is unaware of what they are missing. My social network may consist of a mix of the causes I care about, artists who challenge my thinking, independent news organizations I trust, some friends and family, and even a few businesses I like. But what I select is not what I see—at least not entirely. And this is a system that puts artists and nonprofits at a disadvantage.

In the past two years, we’ve seen this problem get worse. After the 2016 election, the C4AA began considering this decision more seriously, and after much internal discussion among our leadership and a few board members, along with last week’s indictments, we felt it was time. As much as Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg claim to want to build community and bring the world closer together, their business decisions tell another story.

For some nonprofits, paying Facebook for access to supporters is a deal they’re willing to make. No judgment here. C4AA staff still use it to stay in touch with friends. Many organizations we work alongside use Facebook for advocacy efforts. We know for some it may not be a reasonable option to withdraw. We’re not insisting anyone needs to adhere to some arbitrary purity standard. We’ve just decided Facebook is not for us.

For now, we’ve found our email newsletters much more effective because at least we know the message reaches the subscribers’ inbox. And while we are no longer investing our time or our donors’ money into Facebook, it’s not a complete departure. We’re letting automated systems repost from our website and from other social networks.

Leaving history’s biggest social network feels risky. We don’t want to lose those 4,000-plus people—though, in a way, they’ve been lost for a long time. And we remember: It’s not that big of a deal! This makes us only slightly more radical than the Unilever Corporation.

If you’re at a nonprofit and wondering what you can do, have a conversation with your leadership and make a conscious choice. Look at your Facebook stats. Are you reaching your audience? Is paying worth it? Is the money, content, and audience you give Facebook consistent with the goals and mission of your organization?

The Center for Artistic Activism is at C4AA.org. You can sign up for the Center for Artistic Activism email newsletter here. You could also follow us on Facebook, but what would be the point?

Steve Lambert is an associate professor of new media at the State University of New York at Purchase College, a co-founder and co-director of the Center for Artistic Activism, and an artist whose work can be seen at visitsteve.com.