The Shed is nothing if not designed to catch attention. And for what it is costing, let’s face it, it better catch attention: the state-of-the-art kunsthalle-cum-bandstand is being built for the modest cost of a half billion dollars—including $75 million personal donation from Michael Bloomberg, on top of the $75 million the city appropriated for the project under his mayoralty, back when it was still called the Culture Shed.

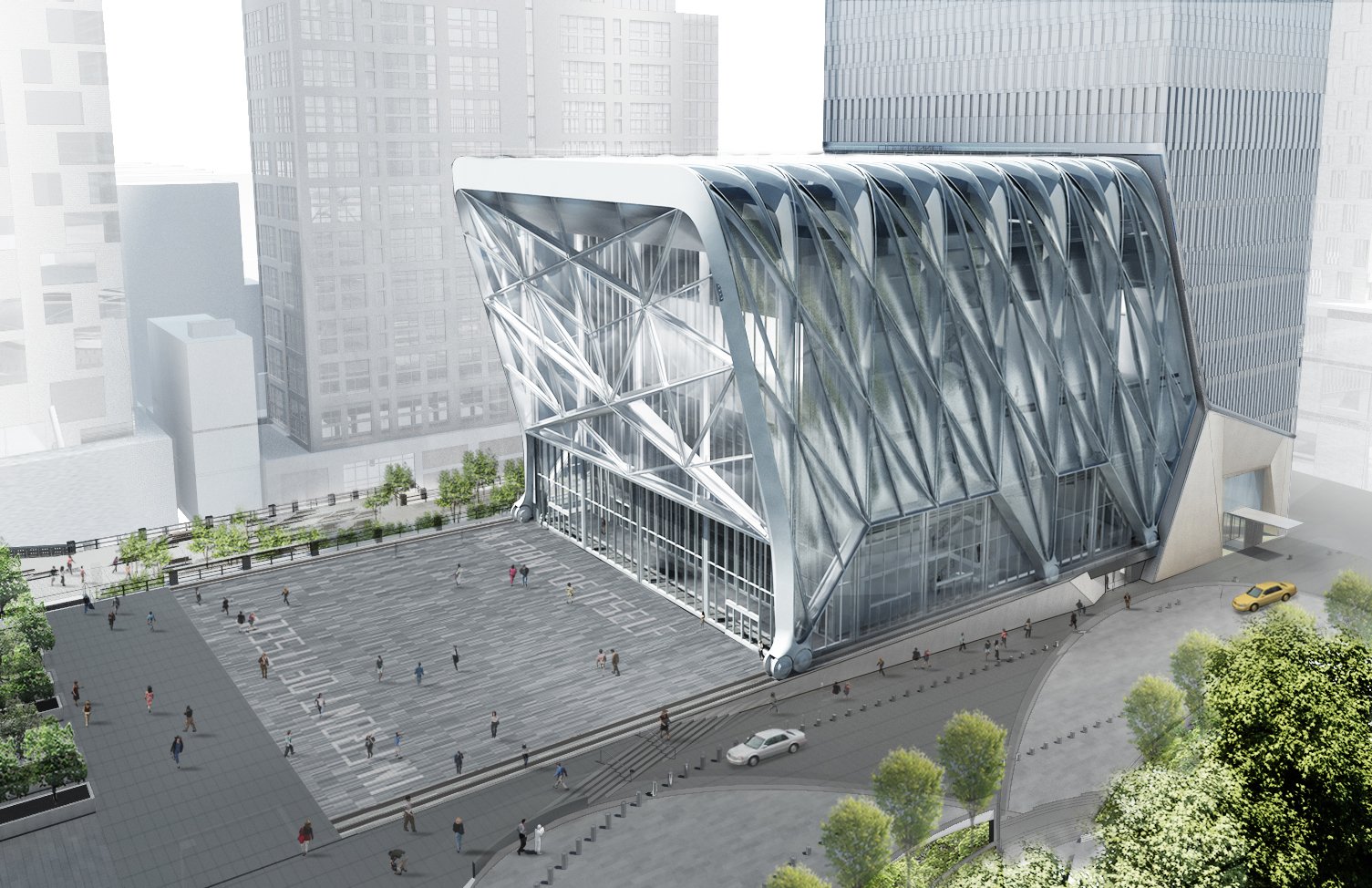

The Diller, Scofidio & Renfro/Rockwell Group-designed final structure won’t open on the High Line until next year. Created as a transformable, mixed-use space and under the direction of Alex Poots, who helmed the Park Avenue Armory as it became a locus for large-scale spectacle art, the Shed boasts that it is the first cultural venue that has been conceived, from the ground up, to commission and host new work from all the arts, from “Kanye West or Björk or Kenneth Branagh, Steve McQueen, Matthew Barney or FKA twigs,” as Poots puts it.

Groovy as that sounds, a sense of superfluity has hovered over an initiative that the Shed’s board chair Daniel L. Doctoroff calls “America’s largest cultural startup.” Along with Thomas Heatherwick’s immense staircase-to-nowhere folly, to be sited nearby in Hudson Yards, and the Barry Diller-backed leisure island in the Hudson River just down the waterline, the Shed would seem to be a testament to an urban program now given over to buying big new toys. Why New York needs a Shed is not clear, and at times even the people presiding over the whole thing haven’t been that clear.

The Prelude to the Shed. Image courtesy the Shed.

And so, for the last two weeks, something called the Prelude to the Shed welcomed curious crowds to a temporary pop-up structure in the shadow of the Shed’s construction site, with the goal being to get people excited. The Prelude amounted to a quirky structure, designed by architect Kunlé Adeyemi, made of mobile black leather benches that could be locked together as walls to form a black-box theater or broken apart to create an open-air stage—a teaser for the protean spirit that the Shed aspires to conjure, in much more high-tech form, when it is completed nearby.

Event programming included performances by Azealia Banks—famous for her offbeat anthem “212” and on-again, off-again fervor for Donald Trump—as well as a live work, This Variation, choreographed by the artist Tino Sehgal. The latter involved a cluster of dancers chanting in unison and dancing in the darkened, closed Prelude space, then opening up the moving panels/benches, their rhythmic sounds periodically giving way to moments of personal confession. (New York‘s Justin Davidson has an account of the experience.) All this was meant to show off the kind of media-crossing experimentation that the Shed hopes to capture, and it was cool.

From my point of view, however, the most important event of the Prelude was this: the Shed has put out a manifesto.

It is 50 pages long, penned by Bard College Berlin curator and scholar Dorothea von Hantelmann, and it was offered to all takers at the pop-up. Lest there be doubt that this pamphlet holds an answer to the lingering “why” hanging over the entire enterprise, it opens by asking grandly: “If the theater was the ritual place of Greek antiquity, the church that of European medieval times, and the museum that of modern industrial societies: What is the new ritual space for the 21st century?”

For those who are still asking, “How can New York afford the Shed?” the manifesto, in essence, boldly asks back, “How can New York afford not to have the Shed?”

The Reformatted Gesamtkunstwerk

So what is the mission of the Shed?

Societies of antiquity, von Hantelmann argues, were held together by the cultural ritual of the theater, which allowed people to come together in one space, and at one time, to visualize their community. But modernity brought a new sensibility that was serviced by the modern invention of the museum, which, von Hantelmann maintains, created a new cultural style more appropriate to the spirit of liberal individualism. Objects that were once experienced as part of acts of ritual togetherness were now placed in a context where individuals could wander among material treasures in their own, distracted, singular, secular, skeptical ways.

The Shed Manifesto. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Now, in the culturally fractious second decade of the 21st century, society’s lack of ritual cultural connections has become an increasingly pressing problem. Thus, von Hantelmann argues, present conditions point to—nay, they demand!—a bold new kind of cultural space, one that goes beyond the museum’s spaces of individualistic contemplation. Because, she writes, “a format that historically served to propagate the mentality of a dualist, anthropocentric, and colonizing Western modernity can only to a certain point now serve to overcome that mentality.”

In the pamphlet’s final section, “Towards a New Ritual,” von Hantelmann explains the kind of new cultural form she has in mind:

[E]ven though it has claim to the discursive power of the visual art world, and also connects to the idea and social function of the museum as a site of long-term value production, this new ritual will not place visual art, and maybe not even a modern conception of art, at its center. A party can be treated with the same rigor and aesthetic sensitivity that is currently attributed to a painting or a theater piece… What used to be an exhibition of ‘works’ (in the sense of separated, distinct entities) would now become an interplay of gatherings responding to a given, often fleeting, set of circumstances, such as the time of day, the number of visitors, and the social fabric of the participants.

The Shed is thus figured as some kind of teleological next stage of cultural evolution, taking the modern museum beyond its flirtation with performance. (“The sheer bringing together of different art forms under one roof does not mean that they necessarily connect,” she writes.) It is offered as a new and higher synthesis between the communal virtues of ritual and the individualistic virtues of contemporary art.

You gotta respect the sheer audacity of this account—though I also think it is firing some pretty heavy philosophical artillery at a straw man.

The Shed, under construction at Hudson Yards March 6, 2018, in New York. Image courtesy Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images.

One only arrives at the intellectual vantage point where the institutional gesture of treating a party as art represents the overcoming of “dualist, anthropocentric, and colonizing Western modernity” if you have abstracted the symbolisms associated with “collective” vs. “individual” experience to the point where these themes float free of any concrete history or politics that might be meaningfully overcome.

I mean, think of it: The 19th-century European cultural world von Hantelmann references was at least as obsessed by experiences of cultural togetherness as it was by models of “liberal,” individualized contemplation. The opera, in particular, was wildly popular as a cultural ritual of collective social symbolism, where high society went to see and be seen (indeed it was a ritual that proposed its own sort of synthesis of the arts, in Wagner’s invocation of the Gesamtkunstwerk, and thus probably a more crucial precedent to wrestle with than the modernist museum). It’s just that it was specifically bourgeois cultural togetherness.

And in some way, one thinks, the Shed’s luxe intermedia aspirations have to be seen as a logical development of this basic dynamic, not some kind of break beyond it.

The Buried Foundation of the Shed

Von Hantelmann philosophical apologia for the Shed is so abstract that one could go on mentioning things her broad-brush account of social aesthetics paints over. But let’s just look at the one positive model that the Shed Manifesto actually does mention, in its final paragraph, as a “ritual that is specific to and appropriate to its own time.”

In fact, everyone involved with the Shed—from architects Diller, Scofidio & Renfro, to super-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, who helped organize the Prelude festivities, to von Hantelmann—mention the same role model as a presiding spirit and legitimating influence: the unrealized 1964 idea of a Fun Palace for London, by the renowned experimental architect Cedric Price (1934-2003).

A model of Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, in an experimental presentation organized by Hans Ulrich Obrist during the Prelude to the Shed. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The Fun Palace was to have been a giant space that could be infinitely reconfigured to host different events of all kinds, as needed. It is ludicrously ahead of its time, proposing amenities that include something that sounds very much like virtual reality, an information kiosk that prefigured the internet, and an “identity bar” where you could try on different personae, as well as sundry educational facilities and equipment for the public to make art and film of their own. All of these features could be expanded or reduced thanks to a system of cranes that could quickly reconfigure its mobile walls.

The notion was very much a product of Swinging London, in an era when old-school bourgeois cultural authority was ceasing to be the choice way to generate social distinction, being gradually displaced by the cachet of youth and fashion and general newness. The Fun Palace’s flexible architecture was meant as a tool that would practically enable popular, grassroots control over cultural space once deemed to be the province of a crusty elite. It was not just an abstract exercise in genre-blurring to provoke some kind of new sense of media-mixing “togetherness.”

A presentation of documents related to the Fun Palace during the Prelude to the Shed. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Yet, at the same time, class distinctions were not going away in postwar England. In fact, the Fun Palace very self-consciously took its raison d’être as working through the evolving class situation. As Price and his collaborator, theater director Joan Littlejohn, wrote of their mission:

Automation is coming. More and more, machines do our work for us. There is going to be yet more time left over, yet more human energy unconsumed. The problem which faces us is far more than that of the ‘increased leisure’ to which our politicians and educators so innocently refer. This is to underestimate the future. The fact is that as machines take over more of the drudgery, work and leisure are increasingly irrelevant concepts. The distinction between them breaks down. We need and we have a right, to enjoy the totality of our lives. We must start discovering now how to do so.

This proclamation is very ‘60s in its assumption of an “affluent society.” It was, however, prescient, even if the reality it augured was rather less “fun” than projected. They were in effect describing the rising prominence of the “creative class” (or “knowledge class”) in the image of the city, as the counterpoint to the incipient deindustrialization and technological disruption of the old industrial working class.

It is thus improper to call Price and Littlejohn’s architecture “utopian”—in the sense of an imagined but impossible ideal place—since its experimental proposal was not only completely practically worked out (it was only problems gaining the proper permits that killed it), but also rooted within the realities of an evolving capitalism. Price would go on, with Reyner Banham, Paul Barker, and Peter Hall, to co-sign the manifesto “Non-Plan: An Experiment in Freedom,” extending the Fun Palace’s critique of fixed architectural infrastructure to the rigidities of top-down social democratic government planning. This idea of non-planning spawned, via Peter Hall’s pragmatic evangelism, the idea of an urban policy centered on “free enterprise zones” that caught fire under Margaret Thatcher, and which has since pitted cities around the world against one another in slashing taxes and regulations to attract entrepreneurs and business, with non-utopian results.

That takes us somewhat far afield from the actual Fun Palace plan though. The Palace itself was undoubtedly prophetic—but both in its positive ideas and in its hints of their darker underside. How would you, practically, create architecture that responded to a public’s needs, without the intermediation of bureaucrats or authorities? The answer, Price and Littlejohn decided, lay in the emergent discipline of cybernetics, and they brought in a key theorist, Gordon Pask, to help imagine the necessary technical systems.

Pask’s scheme for the Fun Palace was considerably less anarchic and dreamy in tenor, and much more a prefiguration of our own present-day algorithmic technocracy. As Stanley Matthews explains in an essay on the social context of the Fun Palace:

That the Fun Palace would essentially be a vast social control system was made clear in the diagram produced by Pask’s Cybernetics Subcommittee, which reduced Fun Palace activities to a systematic flowchart in which human beings were treated as data. The diagram produced by the committee described the Fun Palace as a systematic flowchart. Raw data on the interests and activity preferences of individual users was gathered by electronic sensors and response terminals, and then assigned a prioritized value. This data would then be compiled by the latest IBM 360-30 computer to establish overall user trends, which would in turn set the parameters for the modification of spaces and activities within the Fun Palace. The building would then relocate moveable walls and walkways to adapt its form and layout to changes in use. The process would constantly refine itself by feedback cycles which compared the responses of people coming in (‘unmodified people’) with those of people leaving (‘modified people’).

Essentially, the Fun Palace foretold a world of experience-generating machines relentlessly harvesting data about audience preferences, and optimizing themselves for the most popular content, in a feedback loop. In the cold light of the present, you could call this Buzzfeed architecture.

Something Gained, Something Lost

It makes sense that architects and thinkers would return to Price’s idea of a mutable architecture now, at a time when pop-ups and migrating structures are hot, and an infinitely remixable and responsive internet has made interactivity into the core value of culture. Still, it is worth chewing on the fact that Price himself saw his scheme as having exhausted its use as a progressive architectural ideal after 1975, at least according to Matthews: “Price regarded the Fun Palace as specific to its time and place, and adamantly opposed the idea of reviving the project, or revisiting it in light of contemporary practice.”

So, despite a lavish attempt at intellectual justification, in the Shed and its Prelude you are still left with revolutionary form and revolutionary promises that don’t exactly connect.

The fledgling super-institution is armed with lots of cash and the access to world-class talent that it conjures. The genre-blurring may even produce something great. It is already teasing an opening highlighted by a vast spectacle, staged by video artist turned Academy Award-winning film director Steve McQueen with the hit-making producer Quincy Jones, tracing the history of African American music. It has partnered on a program of “dance activism” with institutions across the city. It even promises to “provide space for protest and creative action through writing, storytelling, and visual art workshops” within the next-level-gentrified Hudson Yards/High Line corridor.

While these latter are fine things to do, it remains unclear why you needed a state-of-the-art Shed to do them. If you really want to talk cultural democracy or social mission, the City of New York has only just gone through the lengthy exercise of formulating a Cultural Plan, staging dozens of meetings with a reported 188,000 people cross the five boroughs—from dancers to art educators, from groups promoting Native American arts to organizations advocating for the advancement of diasporic African and Caribbean artists.

And the number-one demand, throughout that process, concerned the desperate need for affordable space for all the institutions that are already here, in a city given over to luxury amenities, where the immense majority of government cultural funding and private donations alike go to a tiny minority of mega-institutions.

Through that lens, I think that you can see the programmatic diversity of something like a Shed, aspiring to concentrate a lot of culture in one flashy crowd-pleasing project, as not the next and higher level of culture, but as the imaginary compensation for the real, grassroots diversity that is being left to malign neglect.