Art Criticism

There Has Never Been a Tom Wesselmann Show Like This

The Fondation Louis Vuitton's Tom Wesselmann exhibition rewrites the Pop Art narrative and proves that the world is ready for the gargantuan vision of one of the movement's forebears.

Do you know Tom Wesselmann? Maybe you do, maybe you don’t. I left the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris last month feeling sure that we do not know enough about him. And also sure that we’re on the cusp of this changing. There are some key players in the market very set on making this happen.

The institution in a leafy suburb of Paris has made a big-budget gambit to concretize Wesselmann’s role in the history of Pop Art. He is a distinguished member in its pantheon, but he is also somewhat sidelined in favor of easier-to-grab-onto names like Andy Warhol, Yayoi Kusama, and Roy Lichtenstein. A show like “Pop Forever Wesselmann & …” rearranges the cast, moving the artist from supporting actor to lead star, re-contextualizing his contemporaries, predecessors, and successors. The weighty ellipsis in the exhibition headline means that this time, it’s Wesselmann and… everyone else.

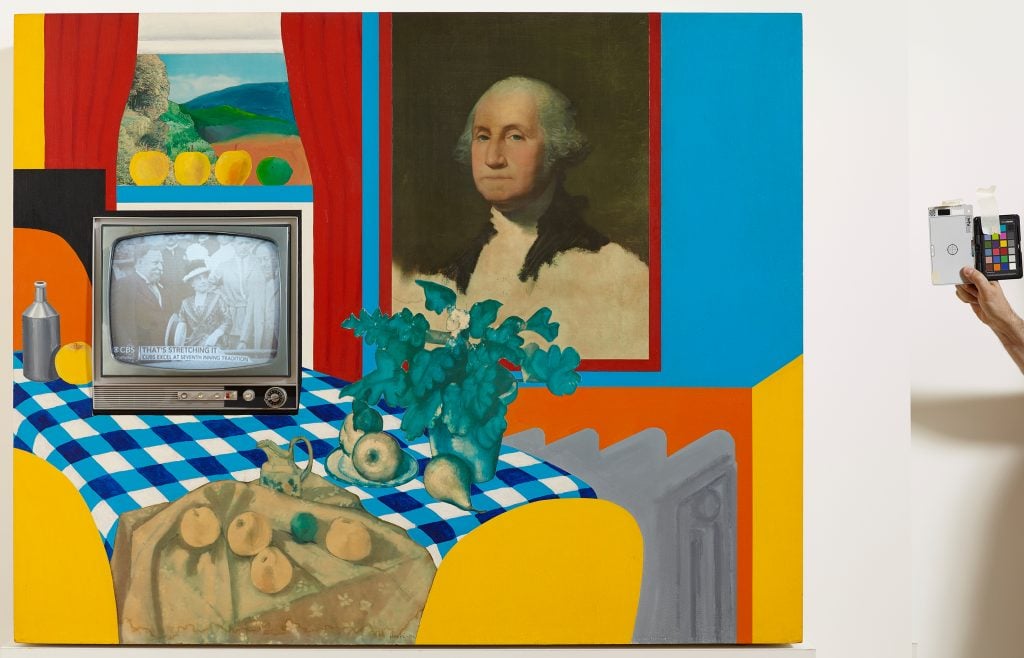

Tom Wesselmann, Still Life #36, 1964. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 20 © Digital image Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala

The privately run museum, which is steered by the group LVMH, has devoted all floors of its building to proving Wesselmann’s deep entanglements with key moments in 20th-century art, looking to Pop Art’s roots in Surrealism and Dadaism as well. I was convinced, converted into a disciple. Every series by the artist has been brought out, in droves. There are 150 Wesselmann works spanning the entire building touching all of his major work cycles, from his most celebrated “Great American Nudes” to his “Bedroom Paintings” and his “Smoker” series. I should say that very few pieces he made are under a meter and half. Many are much bigger than that.

A view of “Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &…” Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2024 © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

There are 35 artists presented alongside him, whose works you probably know better: there is Kusama, Jeff Koons, Ai Weiwei, and Kaws—and none of it is B-roll work. The Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, the headline-making Warhol that art dealer Larry Gagosian bought for $195 million (the most expensive 20th-century artwork ever to sell at auction) is on view. Koons’s Balloon Dog (Yellow) that is in the Cohen collection, the one that shone in the sun on the Met roof is there too. Ai’s Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo series, owned by Larry Warsh, is present as is Marcel Duchamp’s Fontaine, on loan from the Centre Pompidou. The power in these rooms by the collectors alone is palpable.

As we know from Pop Art blockbusters prior, the story of the movement is a story that can be told again, and often is retold, because it works so well as a formula. With the familiarity of popular culture baked into the concept, it calls up a devoted and ever-widening public. But I think there has never been a Pop Art show quite like this. Because there has never been a Tom Wesselmann show quite like this.

Larger Than Life

This is, shockingly, an artist who never got a full-scale museum retrospective in his lifetime. And so “Pop Forever” tries to put it right by including most of his major works, an all-consuming power punch by way of illusion and color, by an artist who never fully subscribed to being part of Pop art. With this scale of work, where elements of paintings protrude from the walls or are plugged into electricity, Wesselmann seems to tower in 20th-century art history. The gambit is successful. His bewilderingly large canvases feel as endless as they feel immersive. They let us indulge in the pleasure of looking. The paint could have been wet on many of these canvases, such is the freshness of thought and the urgency that you can feel pulsing within them.

Tom Wesselmann, Still Life #31, 1963. Photo: Courtesy Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles

The show begins with Still Life #31, a three-dimensional painting from 1963. A television is embedded in the canvas, appearing to sit atop a checkered tabletop alongside fruits, each part of the painting slightly different, references hyperrealism or a Dutch-like tradition. A replica of that famous George Washington portrait hangs on a wall. (Other paintings clearly borrow from Matisse or Rembrandt). On the TV screens, you see John F. Kennedy telling West Germans “ick bin ein Berliner” at the side of the Berlin wall.

Wesselmann’s world becomes a nearly immersive theater. There is a suggestion of a world outside: There are radios humming, affixed to paintings, and in another piece, a phone is ringing, affixed to the painted wall in the three-dimensional canvas Great American Nude #44. Somewhere behind a canvas depicting a drink being poured, and we can hear the infinite sound of wine tumbling into a cup on loop. Windows with a view recur in many works. As the show progresses in time, so does the media that you hear on the many televisions and radios that hang embedded in his paintings works or posed on countertops that are fastened onto canvases. (Jeffrey Sturges, head of exhibitions at Tom Wesselmann estate, told me there that the estate has never been able to assemble so many of these electric paintings.) By the time you reach the last piece in the exhibition, time has moved forward—you now see a live stream of the current French news, which was discussing the Middle East conflict when I was there. To deliver the “now” in his work like this is a gentle but masterful move by the curators.

PARIS, FRANCE – OCTOBER 15: A general view of the Louis Vuitton Foundation during the press preview of the exhibition “Pop Forever. Tom Wesselmann & …” at Louis Vuitton Foundation on October 15, 2024 in Paris, France. (Photo by Luc Castel/Getty Images)

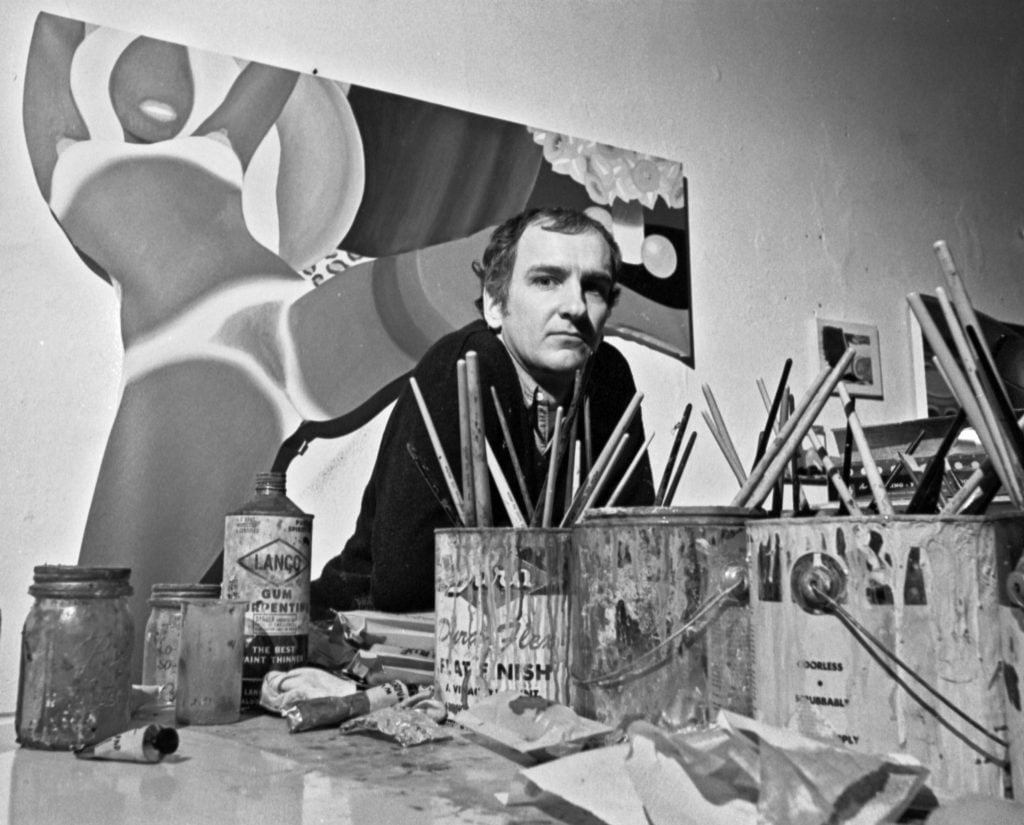

Artist Tom Wesselmann photographed in his studio in March 1969. (Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images)

Celebrated works by artists are carefully woven in. A room with surrealist Meret Oppenheim’s sugar ring from the mid-1930s, a ring with a little white sugar cube embedded as a gemstone, is absurdist and calls attention to the artifice and cheapness in a way that Pop Artists were keen to emulate. Artists who riff off of Pop Art, like Sylvie Fleury, are on view—her smashed car, which was painted with nailpolish and is called Skin Crime 3 (Givenchy 318), 1997, is among other key female artists who are on view helping to rebalance the dominating narrative of Pop Art, which is white and male.

But the pinnacle of Wesselmann’s signature comes in the way he wields grandiosity. You feel astoundingly small walking past a light switch as big as a doorway, you sense your body and mind tilt as you walk by towering paintings of a Budweiser can and a pack of Pall Malls that are as tall as you in Still Life #33. Popular culture begins to feel like a forest of tall trees: Oranges, lipstick containers, tan lines tower, white bread bulges off a misshapen canvas, consumer items recur in clusters and they are mundane but they are also gigantic, and never too realistic. It always comes back to the painterly or the drawn line.

A general view of the Louis Vuitton Foundation during the press preview of the exhibition “Pop Forever. Tom Wesselmann & …” at Louis Vuitton Foundation on October 15, 2024 in Paris, France. (Photo by Luc Castel/Getty Images)

You feel you could step into the mouths from his “Smoker” series, carefully shaped canvases showing smoke undulating out of agape red lips. This is adult fantasy mixed with childlike wonder; that pull on our hearts that we felt as a child, wishing to be able to enter your dollhouse or jump into a picture. Optical illusions ensnare the imagination: collages depicting a young boy drinking soda renders the rest of the painted canvas at once more and less real; he is seated at a table where there is milk and pineapples (painted), there is a replica of a Canada Dry bottle (real) but it is filled with what looks like orange paint. There is a painted radio and a real one which is turned on. American stars deny any semblance of white space and there is a photocopied vista of a building out of a real window. Everything is familiar, everything is rendered foreign.

A view of “Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &…” at Fondation Louis Vuitton. Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2024 © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

“You can never confuse a Wesselmann with anything,” said Daniele Thompson, an art collector who was also a subject and muse for the artist, in a video just outside of the galleries. Hard to tell, but she was the mouth of Smoker #20, a rare black-and-white oil version of the series, which was on display at Gagosian’s booth at Art Basel Paris last month and sold on opening day.

Pop Market Forever

Born in Ohio, Wesselmann went to Cooper Union, maintaining a large studio at Cooper Square in Manhattan for most of his working life. He had initially hoped to become a cartoonist before finding his way to fine art. As a young artist, he was transformed by a Robert Motherwell painting, Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 108. The large abstract canvas has deep black blots on it that seem to pop beyond the picture plane, while, at the same time, being contained by the boundaries of the painting. “He felt a sensation of high visceral excitement in his stomach, and it seemed as though his eyes and stomach were directly connected,” wrote Wesselmann, writing about his own work in the third person under his nom de plume, Slim Stealingworth. He would use the alias for years, feeling that critics did not adequately understand or process his work. For much of the 1960s, writes Wesselmann’s alter ego, “he used this same feeling to determine the completion of his own paintings.”

A general view of the Louis Vuitton Foundation during the press preview of the exhibition “Pop Forever. Tom Wesselmann & …” at Louis Vuitton Foundation on October 15, 2024 in Paris, France. (Photo by Luc Castel/Getty Images)

He suffered from heart disease and died in 2004. At the time of his death, he was recognized, but had never had a major institutional retrospective in his lifetime. The first opened at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2012, travelling to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the Cincinnati Art Museum afterwards.

But the narrative that Wesselmann is overlooked is not true. One need look no further than the fifteen works on view that notably stem from the collection of the Mugrabi family. But he is under-considered when it comes to the market and a consortium is present, intent on changing it and in particular, how institutions see and incorporate his work.

“Wesselmann chose to work with Sidney Janis instead of Leo Castelli, who famously championed artists like [Jasper] Johns, [Robert] Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, and Warhol, so perhaps that may have had some impact on how he was perceived,” said Jason Ysenburg, director at Gagosian, which works with the artist’s estate. “The number of museum loans featured in the show at Fondation Louis Vuitton speaks to how highly regarded and respected Wesselmann is by institutions. Sometimes the market can take a little longer to catch up in terms of comparable recognition.”

A view of “Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &…” Photo: © Adagp, Paris, 2024 © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

In some of the show, the market forces are all-too palpable. Most heavy-handed are new commissions by artists Derrick Adams (represented by Gagosian) and Tomokazu Matsuyama (represented by Almine Rech, which works with Wesselmann’s estate). As artists, they take inspiration from his work, which one can see and feel convinced by in other parts of their practice; but these made-to-fit pieces in “Pop Forever” feel too on the nose with their references to work in the show. Commissions by Mickalene Thomas and previously existing work by Do Ho Suh and Njideka Akunyili Crosby feel like much more easygoing fits, without trying too hard and being too in-the-pocket of the supporters of this show.

This show is plainly too exciting to walk around it to be left thinking about who is trying to make the Wesselmann stock go up; for me, that got a pass when I came to the top floor gallery, a grand finale of sorts: his “Standing Still Lifes.” Four massive works, on loan from the estate, loom at astonishing heights of two or three meters tall, and almost 10 meters long. These propped-up shaped canvases—a key, a ring, a cigarette butt, a toothbrush, lipstick, nail polish, sunglasses—create sacred totems out of banal products. The paintings reverse sides are visible when you walk behind them, a dark but apparent “means of production” that never let you fully step into this illusory world. And that childlike feeling returns, or, to use Stealingworth, that feeling in your stomach—you want to reach out and touch this work—that feat of Wesselmann makes it an easy, and brilliant, sell.