Art World

10 Remarkable Revelations From a New Biography on Trailblazing Art Patrons John and Dominique de Menil

In addition to assembling a world-class art collection, the de Menils were also progressive activists.

In addition to assembling a world-class art collection, the de Menils were also progressive activists.

Alina Cohen

In the first-ever biography of the visionary 20th-century philanthropists Dominique and John de Menil, out last week from Knopf, author William Middleton details, over nearly 800 pages, how the couple built one of America’s most impressive art collections and opened the Menil Collection and Rothko Chapel in Houston.

But Double Vision: The Unerring Eye of Art World Avatars Dominique and John de Menil also happens to span three centuries and serves as a decent primer on French politics, the Vichy government, Venezuelan architecture, oil prospecting, Catholicism, Houston, and the New York art world, too. Middleton goes so far as to detail Dominique’s great-great-great-grandfather’s death by guillotine for supporting the French Revolution.

In Middleton’s telling, the de Menils’ lives and family histories become about far more than their aesthetic decisions. Ultimately, the author is most interested in his subjects’ singular ambitions, progressive attitudes, and famous, globe-spanning friendships. These interests bring the narrative full circle: liberté, égalité, fraternité indeed.

The expansive book is full of surprising revelations, 10 of which we’ve highlighted here.

When World War II broke out, John, who Dominique married in 1931, was living in Bucharest, Romania, running his family’s oil business. The Deuxième Bureau, a French intelligence agency, assigned John and a small team to sabotage shipments of oil and other goods bound for Germany. For his achievements, he received the Croix de Guerre military award.

Her great-great-grandfather, François Guizot (1787-1874), co-founded a literary journal, lectured at the Sorbonne, and served at the French Ministry of the Interior under the last king of France (Louis Philippe). He bought Val-Richer, a massive estate in Normandy. Writer André Gide was a neighbor and friend. Dominique spent much of her childhood at the estate, immersed in tales about her legendary lineage.

The wedding of Dominique and Jean de Menil, May 9, 1931, in Paris. Photo: courtesy of De Menil Family Papers, Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston.

Dominique once said she’d burn in hell for the way she treated her children. She and her husband left their young children for years at a time. A telling note from her to John reads, “Nature, like children, absorbs and smothers you.” John once wrote to Dominique that he wasn’t really cut out to have children. And yet, they had five: Christophe, Adelaide, Georges, François, and Philippa.

The de Menils didn’t like Ernst’s Portrait of Dominique at first, rejecting its browns and dark blues, and the seashells he painted around her face. But eventually the work became a crucial part of the couple’s expansive Ernst collection, which grew to 103 paintings and sculptures. Along with works by René Magritte, Man Ray, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy, these contributed to perhaps the most important surrealism collection in the world.

The Oceanic galleries of the Menil Collection, 1987. Photo: Hickey-Robertson, courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston.

Father Marie-Alain Couturier, an advocate of the connection between spirituality and modern art, advised the de Menils’ purchases and introduced them to work by leading European artists, including Piet Mondrian. The de Menils also acquired more than 450 works from Alexander Iolas, a legendary Greek dealer and former dancer who was known for his panache. As Middleton nicely sums up, “One of Couturier’s preferred artists was the often spiritual Rouault, while one of Iolas’s early favorites was the sensualist Bérard.”

The de Menils moved to Houston in the 1940s to escape the war and establish their oil business. They wanted to build a striking new home that would jump-start the city’s cultural relevance, so they hired architect Philip Johnson, founder of the Museum of Modern Art’s department of architecture and design (though they turned to New York fashion designer Charles James for the interior). Throughout the ensuing decades, such cultural icons as Norman Mailer, René Magritte, Susan Sontag, and Philip Glass all visited the home. Transgender actress Holly Woodlawn (the inspiration for Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side”) once allegedly swiped things from the home.

During World War II, Dominique opened a boutique in Caracas, Venezuela, (where Jean was based for work) called La France. She designed tables, selected merchandise, and commissioned local seamstresses to produce clothing. All proceeds went to the French Resistance. On the side, she found time to write articles and take photographs, too.

Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk (1963-1967), dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr., in front of the Rothko Chapel. Photo: Hickey-Robertson, courtesy Rothko Chapel Archives.

In 1960, Mark Rothko was slated to create a series of paintings for New York’s Four Seasons restaurant but nixed the project after deciding the venue was too frivolous. During their first-ever studio visit with the artist, the de Menils suggested they install the works in a Catholic chapel they planned to build instead. Rothko partly agreed; but decided to paint a new suite of murals for what would ultimately became Houston’s non-denominational Rothko Chapel.

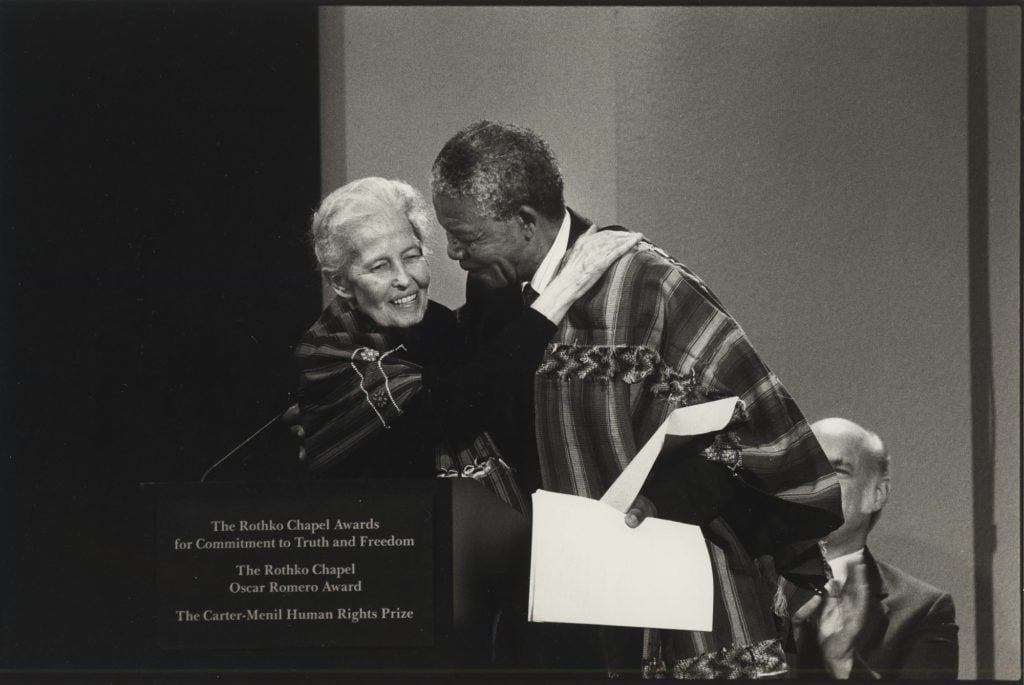

Dominique de Menil with Nelson Mandela at the Rothko Chapel, December 1991. Photo courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston.

In the 1960s, John de Menil and a group of businessmen helped desegregate Houston by quietly taking down the city’s “white” and “colored” signs. John financed civil rights activists, ranging from local students to politicians, and supported the SHAPE (Self-Help for African People Through Education) Community Center. After his death, Dominique and Jimmy Carter co-founded the Carter-Menil Human Rights Prize for global leaders, which came with a $100,000 award. For the 20th anniversary of the Rothko Chapel in 1991, Dominique hosted a gala and honored Nelson Mandela with a comparable prize after he delivered a keynote speech to an audience that included Carter, major Texas politicians, and Bianca Jagger.

The Menil Collection, architecture by Renzo Piano. Photo: Hickey-Robertson, courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston.

In 1973, John de Menil died after battling cancer for six years. In 1987, Dominique opened the Menil Collection, designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Fitzgerald & Associates. The museum, filled with works from the antiquities to the present, secured their legacy as one of the country’s greatest patron couples. Dominique died in 1997.