Archaeology & History

5 Surprising Facts About the Parthenon Marbles (Including the Existence of a Near-Perfect Replica in Nashville)

From robots to diplomatic embarrassments, the sculptures have a colorful history.

From robots to diplomatic embarrassments, the sculptures have a colorful history.

Hannah Cunningham

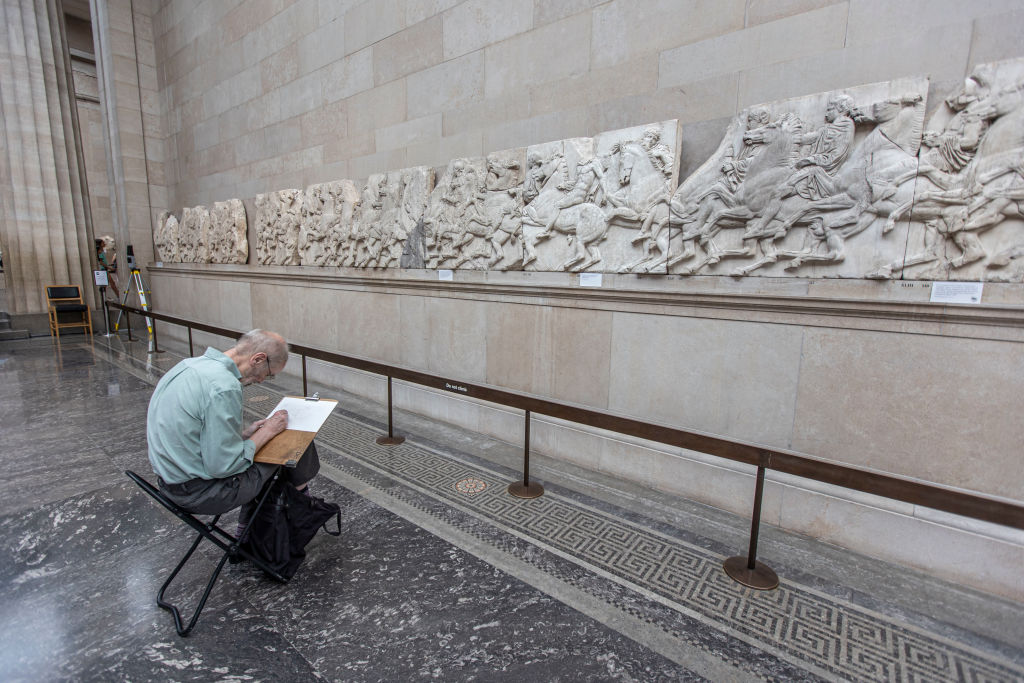

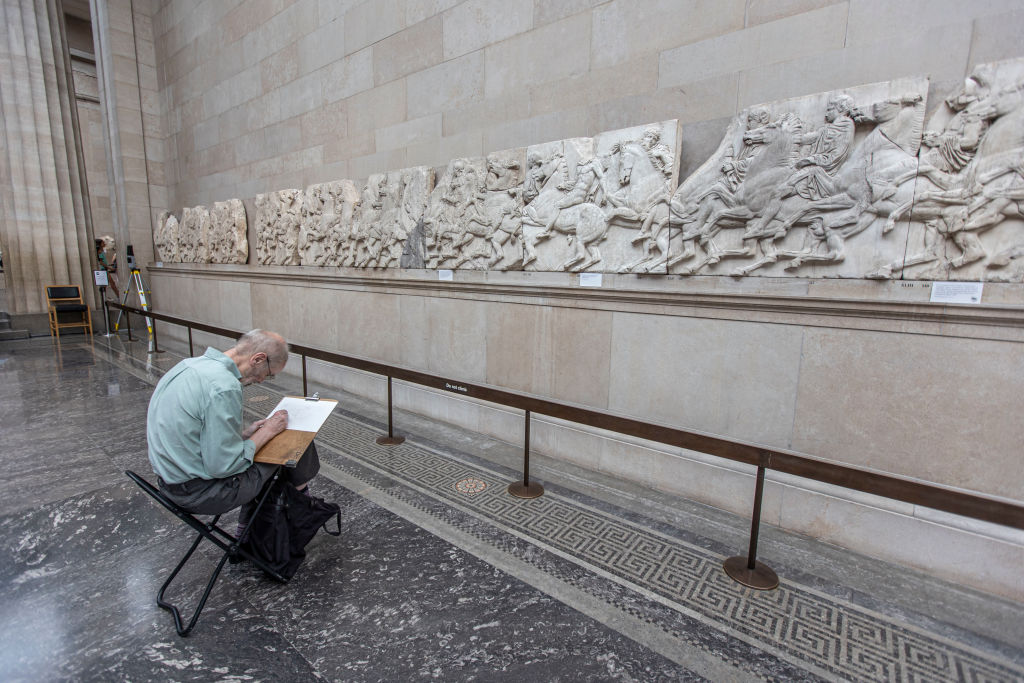

It’s hard not to be awestruck standing in front of the Parthenon marbles. The collection of sculptures adorned the famous archeological site, which was originally built as a temple to Athena in mid-400 B.C.E. and is one of the best examples of classical architecture remaining today. It’s the crown of the Acropolis in Athens, and the sculptures are its crowning jewels. That said, if you’re standing in front of them today it is more likely to be in the ascetic setting of the British Museum than feeling the wind in your hair in the ancient citadel overlooking the Greek capital city.

The why has been for decades the center of an international debate on repatriation. In the early 19th century, a British diplomat, Lord Elgin, ordered the removal of around half of the sculptures, which were gifted to Queen Victoria and have sat in the British Museum ever since. Greece, unsurprisingly, isn’t thrilled about this, and Greek officials have long advocated for their return, insisting they were stolen. (Most recently, the Greek Culture Ministry held an international meeting at the Acropolis Museum on Friday, calling again for the repatriation of its precious heritage).

The British Museum maintains it is the legal owner of the Greek artifacts. While the debate plays out, the Acropolis Museum has subbed in plaster copies in place of the originals among its Parthenon collection, awaiting the return of the missing pieces from London. The ownership dispute is perhaps what the Parthenon marbles are best known for, but they are so much more than that: here are five surprising facts you didn’t know about them.

Boris Johnson at the temple of Parthenon in Athens, Greece in 2012. Photo by Yannis Behrakis-Pool/Getty Images.

Before he was prime minister, Johnson was the president of the Oxford Union and a keen classics student at university. In an unearthed 1986 article, the former prime minister vehemently advocated for the return of the Parthenon marbles to “a country of bright sunshine and the landscape of Achilles.” In a letter inviting Melina Mercouri—former actor and Greek culture minister—to address the union, Johnson wrote there was “absolutely no reason why” the Parthenon marbles should not be immediately returned to Athens.

More recently Johnson has changed his tune, falling in line with the U.K. government’s stance that they were taken legally. Removing himself further from the debate, last year Johnson said their return is “up to the British Museum.” While the trustees of the British Museum claim the Parthenon marbles transcend politics, the fact that Johnson’s decades-old opinion on the marbles became the central topic of a Prime Minister’s Questions session earlier this year proves otherwise.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Phidias showing the Parthenon Frieze to his Friends Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images.

The influence of ancient Greek architecture can be seen in cities all over the world; white neoclassical columns and sculptures have become synonymous with status and power, featuring everywhere from the White House in Washington D.C. to the National Gallery in London. It is somewhat ironic, therefore, that this minimalist homage to classical Greece is actually the opposite of the style at that time. The Greeks loved color and glitz, and their buildings and sculptures were usually brightly painted, the Parthenon included.

Archaeologists have used ultraviolet light and lasers to discover that the Parthenon marbles were originally painted red, blue and green. The marbles at the British Museum show less evidence of color than their fellows at the Acropolis, not because they were unpainted, but because they were subjected to an over-zealous cleaning using copper scrubbing brushes in the 1930s. What was mistaken for dirt was in fact a natural patina on the ancient stone.

Experts at the Institute of Digital Archaeology (IDA) are making replicas of the Parthenon marbles, and engineers are offering a helping hand; or in this case, a robotic arm. Using 3D-scanning and a robot, specialists have carved replicas from rare Pentelic marble (the same kind of marble used for the Parthenon). The institute intends to exhibit the replicas in London nearby the British Museum. This proximity is intentional: viewers will see these sculptures before heading into the British Museum, allowing them to make a comparison. Some replicas will be presented in their original colors, juxtaposing with the worn and faded originals.

Breakthroughs in technology have made replicas like these possible, which could pave the way for wider restitution. If the purpose of an exhibit is to educate, then hyper-realistic replicas unworn by time could be used as a persuasive counterpoint in restitution cases beyond the Parthenon marbles.

A tourist holds a parasol as she visits the Ancient Acropolis archeological site in Athens on July 1, 2021. Photo by LOUISA GOULIAMAKI/X07402/AFP via Getty Images.

The Parthenon has undergone many changes throughout its long history. The temple standing today is a reconstruction of an older building destroyed by the Persians during their sacking of Athens ca. 480 B.C.E. In 334 B.C.E., Alexander the Great sent the shields of his conquered Persian enemies back to Athens where they were drilled to the Parthenon walls. Later, Christians repurposed the temple as a church, purposely defacing many mythological figures on the Parthenon marbles.

During the Siege of Athens in 1687, the Turks used the Parthenon for ammunition storage. When a mortar shell hit the building, the ensuing explosion killed 300 people and destroyed the temple’s roof and most of its walls. Today, climate change is a major threat to the ancient monuments on the Acropolis. Air pollution and acid rain are eroding the marble, making the protection of the Parthenon marbles in museums even more important.

Greek Parthenon replica Centennial Park Nashville Tennessee USA. Photo by: Andrew Woodley/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

While Athens and London were feuding over the Parthenon marbles, Nashville was building a full-scale replica of the Parthenon. Built in 1897 as part of the Tennessee Centennial Exposition, the temple was intended to be a temporary structure but quickly became popular with residents and visitors. Because of this, it was rebuilt in the 1920s with the input of classical scholars to be used for events and festivals.

This temple is now an art museum, and in 1990 a towering replica statue of Athena that once stood in the original Parthenon was added, gilt with more than eight pounds of gold leaf. The painted walls and metal embellishments are in keeping with the original style. Because of this, the Nashville Parthenon is one of the best ways to see the Parthenon marbles in their original context, as they would have been seen by Athenians when the temple was in its prime.