Museums & Institutions

Why Is There a Teeny Replica of a Parthenon Marble Hidden in the British Museum? This Activist Group Was Hoping You Would Ask

The effort is intended to spur dialogue around the restitution of the Parthenon marbles.

The effort is intended to spur dialogue around the restitution of the Parthenon marbles.

Richard Whiddington

A tiny horse is hiding somewhere in the British Museum’s Duveen Gallery. How tiny? Smaller than the smallest visible wavelength of light—so tiny it’s extremely unlikely the museum will find ever it. And that’s exactly the way Oxford’s Institute of Digital Archaeology (IDA) wants it.

The 19-micron steed is a perfect replica of the Selene Horse, one of the hotly contested Parthenon sculptures, and the IDA sees it as a perfect fusion of ancient Greek craftsmanship and modern engineering. It’s quite possibly the smallest 3D copy of anything.

The Selene horse was surreptitiously released (along with Pink Panther-esque gloves) by the IDA into the wilds of the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum on April 14 in a move to spur dialogue around the restitution of the Parthenon sculptures. The artifacts were acquired by Lord Elgin from the Ottomans in the early 19th century under dubious circumstances and Greece has long demanded their return.

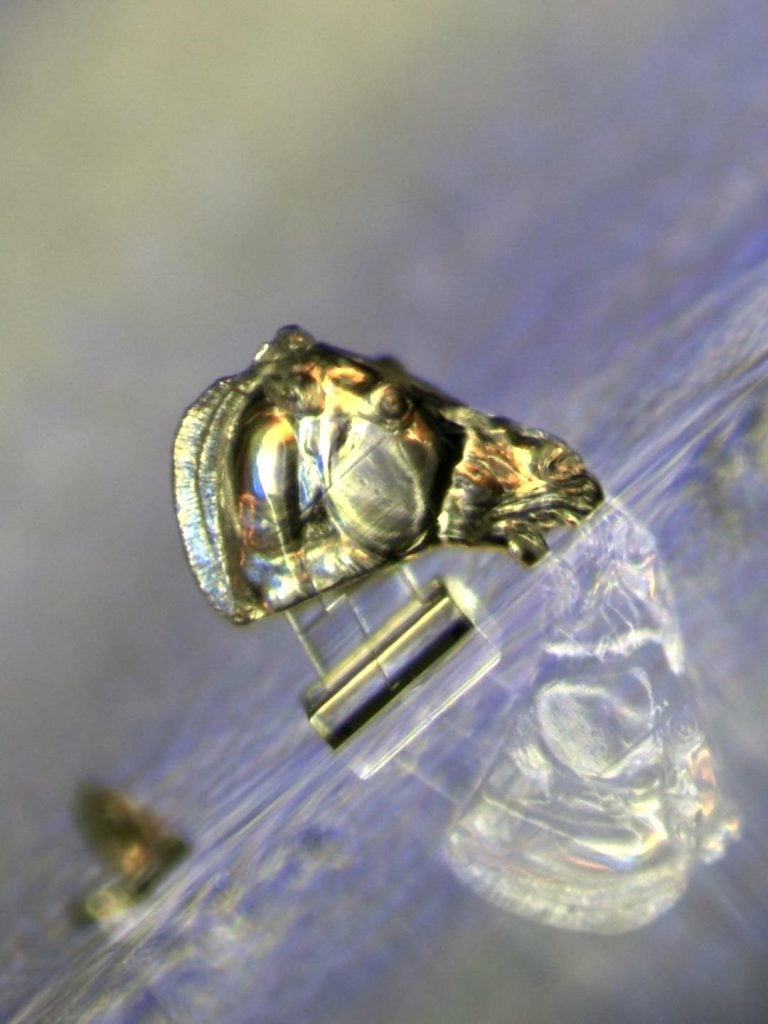

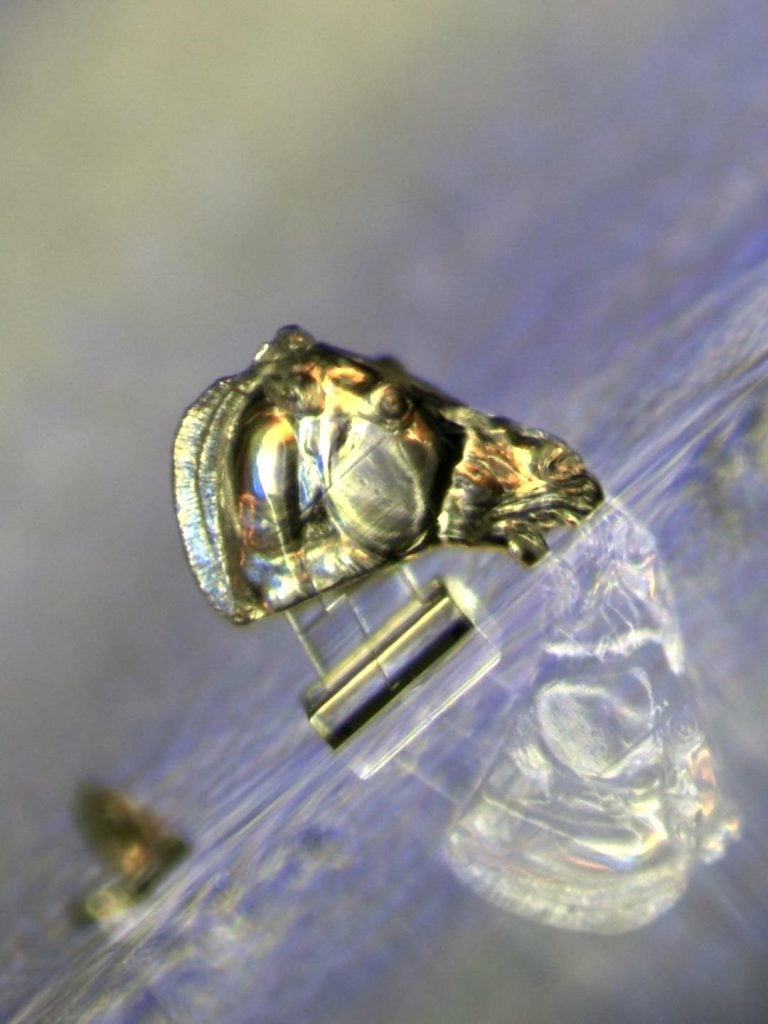

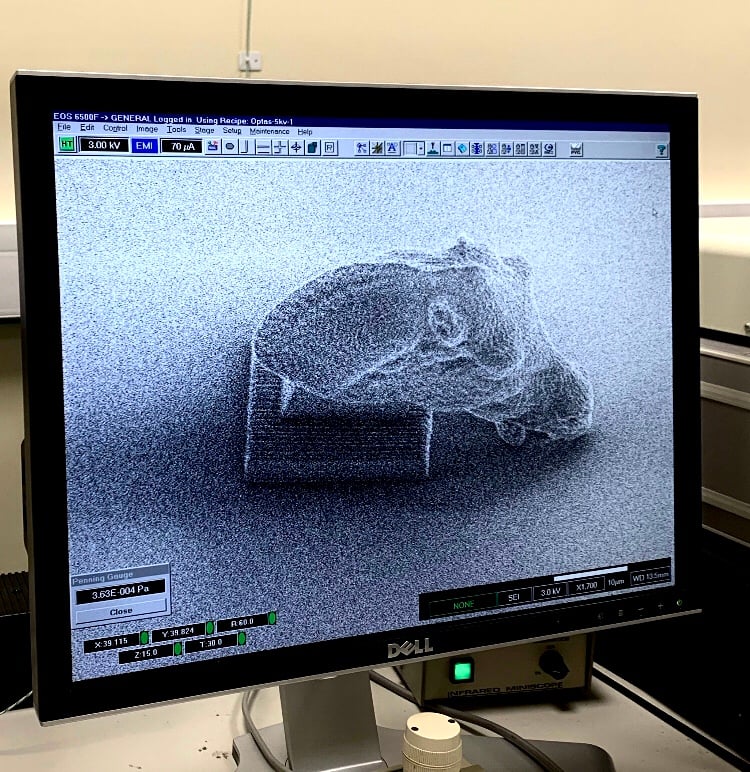

The miniature sculpture of the Selene Horse. Photo: IDA/AD Karenowska

“We wanted to explore ideas of control in relation to historic objects,” Roger Michel, IDA’s executive director, told Artnet News. “The British Museum has sculptures it took from someone else and won’t give back. Now, thanks to us, it has a fairly interesting sculpture in its own right that was forced on the museum, but has no power to remove.”

The British Museum is not interested in a sculpture the size of a speck of dust—in fact, it’s hardly acknowledging the tiny horse’s existence. When asked how the search was panning out, the museum responded to Artnet News saying it was aware of IDA’s claims but had “received no evidence to prove this.”

Michel made light of the museum’s response: “The British Museum is consistent if nothing else. When it comes to historical denialism, nobody is better.”

One of the gloves left behind by the IDA operative. Photo: IDA/AD Karenowska

It’s the second socially-engaged effort the IDA has undertaken over the Parthenon sculptures.

Last year, after being denied permission to scan the 5th-century marbles, Michel and his team scanned them secretly using digital imagery software on tablets and smartphones. They created full-scale reproductions of the Selene horse, along with the famed metope depicting the bloody battle between the centaurs and lapiths at Peirithoos’s marriage. The works were put on display at London’s Freud Museum.

The Parthenon marbles controversy is the perfect ground for IDA to simultaneously engage with questions of heritage and authenticity, while showcasing its expertise in architectural scale reconstruction. For the IDA’s director, confronting the British Museum has a personal element. Michel is fascinated by the place the marbles, and the surrounding debate, holds in Britain’s psyche, and as a lawyer, he is drawn to the legal aspect, one he believes has been largely unexplored.

The miniature Selene Horse as seen prior to being created. Photo: IDA/AD Karenowska

“I will be convening a moot court at Winchester College next month,” Michel said, “joined by legal experts from the U.S. and U.K., to try and resolve the legal questions around the Elgin dispute once and for all.”

The court is unlikely to change opinions inside the British Museum (dismantling the museum’s Parthenon collection, said its chairman, “must not become the careless act of a single generation”), but either way, a tiny horse has left the stable and, just as with its larger relatives, it won’t be going home any time soon.