Analysis

Potential Witnesses Revealed on First Day of the Knoedler Forgery Trial

The stakes are high.

The stakes are high.

Eileen Kinsella

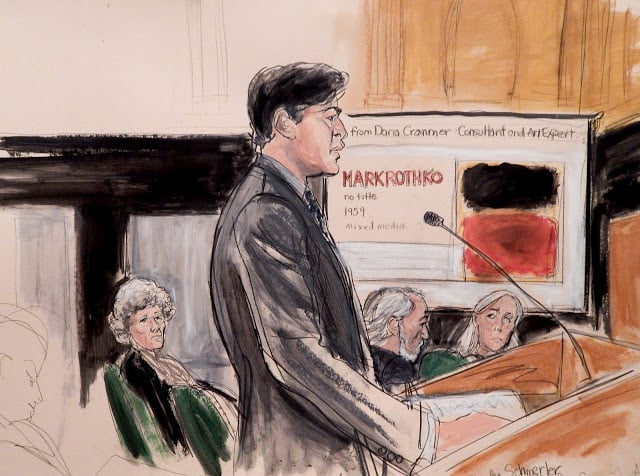

A painting sold by Knoedler as a Mark Rothko that turned out to be fake.

Today marked the start of the first and only lawsuit that has emerged from the protracted Knoedler forgery scandal, which rocked the art world in 2011 and led to the shuttering of one of Manhattan’s most prestigious, long-running galleries. Buyers at the time spent tens of millions of dollars on purported Abstract Expressionist masterpieces that turned out to be the handiwork of a Chinese painter based in Queens, New York.

Plaintiffs Domenico De Sole and his wife Eleanor, along with defendant and art dealer Ann Freedman, are all expected to testify in the trial, which is expected to last four weeks. Attorneys for Knoedler, the gallery she presided over for many years and which is also named in the lawsuit, were also present.

While much of the first day focused on selecting a jury, including questions about potential jurors’ knowledge of art history and Abstract Expressionism in particular, Judge Paul Gardelphe read a lengthy list of names aloud, including those of art experts, in order to determine whether potential jurors recognized any of them.

Judge Gardelphe indicated that Robert Wittman, founder of the FBI Art Crime Team, who now runs a private art security firm, will appear as a witness on behalf of the defense. The two sides have battled over what topics he can discuss, including Freedman’s and the De Soles’ respective responsibilities and efforts to research the work prior to the sale.

A courtroom sketch of Domenico De Sole’s lawyer, Emily Reisbaum, making her opening statement at the Knoedler gallery trial.

Photo: Elizabeth Williams, courtesy ILLUSTRATED COURTROOM.

Many of the names Judge Gardelphe read are familiar from other legal disputes linked to Knoedler painting sales that turned out to be forgeries from Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales. She pleaded guilty just over two years ago, and is currently awaiting sentencing.

According to the New York Times, the list of potential witnesses includes: Christopher Rothko, the artist’s son; paint analysis expert James Martin of Orion Analytical; James Coddington, chief conservator at the Museum of Modern Art; and Laila Nasr, a curator at the National Gallery of Art. Rothko expert David Anfam is also scheduled to testify.

Freedman’s lawyers claimed Anfam was “enthusiastic in his endorsement” of a Rosales-sourced painting but in a deposition Anfam claimed that he never formally authenticated it.

Despite the high stakes and the millions of dollars that were lost, the suit, brought by De Sole, who is a Sotheby’s board member and a former Gucci executive, is the only one to make it to court so far. Even in the three months since artnet News reported that two cases were moving forward, collector John Howard, who purchased the fake de Kooning, settled his case on confidential terms.

At issue in the remaining De Sole case is what Freedman, who brokered this sale and numerous others, knew about the shaky provenance, or history of ownership of these works.

A courtroom sketch of defense lawyer Charles Schmermer making his opening statements at the Knoedler gallery trial.

Photo: Elizabeth Williams, courtesy ILLUSTRATED COURTROOM.

Rosales brought the works to the gallery between 1994 and 2008, with a false story about a mystery collector and his heir who did not wish to be identified. Freedman maintains that she did not knowingly sell fakes.

The 165-year old Knoedler Gallery abruptly shuttered in 2011, almost immediately after collector Pierre La Grange filed a lawsuit over a $17 million painting he bought as the work of Jackson Pollock. Forensic testing by expert James Martin of Orion Analytical revealed that elements of the paint were anomalous with the dating of the work.

This proved to be the case in numerous of the other Rosales works, including purported pieces by Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Franz Kline, and Rothko, where analysis of paint samples pointed to signs that the works were created after the respective artists’ deaths.

Freedman and her attorneys initially challenged the validity of those scientific results but when the forger, Pei-Shen Qian, was identified and traced to Woodhaven, Queens, this argument was eventually dropped. Qian, who has since fled the country, was charged in mid-2014.

Collector Domenico De Sole, who is now chairman of Sotheby’s board, is suing over a Mark Rothko painting that turned out to be fake.

Photo: Courtesy of Sothebys.com.

Also charged in the case was Rosales’s longtime partner, Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz, and his brother Jesus Angel Bergantiños, though there has been no news on possible extradition from Spain, where they were arrested in April 2014.

According to the indictment, Qian lied to FBI agents investigating the forgery scheme, telling them that he did not recognize Rosales’s name and that he was unfamiliar with certain noteworthy artists, including those whose names he “had repeatedly and fraudulently signed” on paintings he created. In Qian’s home, investigators found copies of various Abstract Expressionist paintings he created, books on these artists and their techniques, paints, brushes, canvases, and other materials “such as an envelope of old nails marked ‘Mark Rothko’ all to aid QIAN in creating the fake works.”

Former Knoedler president Michael Hammer, along with Rosales, is named in this and other lawsuits. With a parade of experts and insiders expected to take the stand in the coming weeks, the trial will undoubtedly shine a light into the often murky and secretive practices surrounding high-stakes art sales. It will also raise pointed questions about art dealing and authentication practices, including what constitutes a warranty on a multi-million dollar work.