Art World

An Anti-Corporate, DIY Spirit Uplifts New Queer Art Biennial

Detroit reclaims Pride. 180 artists are featured in "I'll Be Your Mirror," this year's edition of the Mighty Real/ Queer Detroit biennial. Here's our on-the-ground take.

LGBTQ+ Pride has turned into a surreal month-long corporate celebration where brands and politicians bend over backwards to virtue signal their support for queer identities. Pride parades are awash in brand logos and commercial promotions take precedence over honoring gay history, community, and creativity. A much more ambitious and meaningful Pride alternative is on offer with the new queer biennial, Mighty Real/ Queer Detroit.

This year’s outing, dubbed “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” opened May 31st and runs until the end of June. “We can do more than a parade during Pride Month, even people in our own community are unaware of the many ways queer artists contribute to our resilience,” explains Patrick Burton, the founder of the eponymous non-profit Mighty Real/Queer Detroit that has organized the event, America’s largest exhibition of queer art, featuring over 180 artists and 800 works of art at 11 venues throughout the city. “I’ll Be Your Mirror” is the follow-up to 2022’s launch that presented 77 years of Detroit’s homegrown queer art scene. This time around, Burton, who is the head curator and creative director, opened the exhibition to artists both nationally and internationally, with additional curatorial support from artist Billy Miller, who also edits the notorious gay sex journal Straight to Hell. The pair both attended Detroit’s renowned art school CCS in the 1970s.

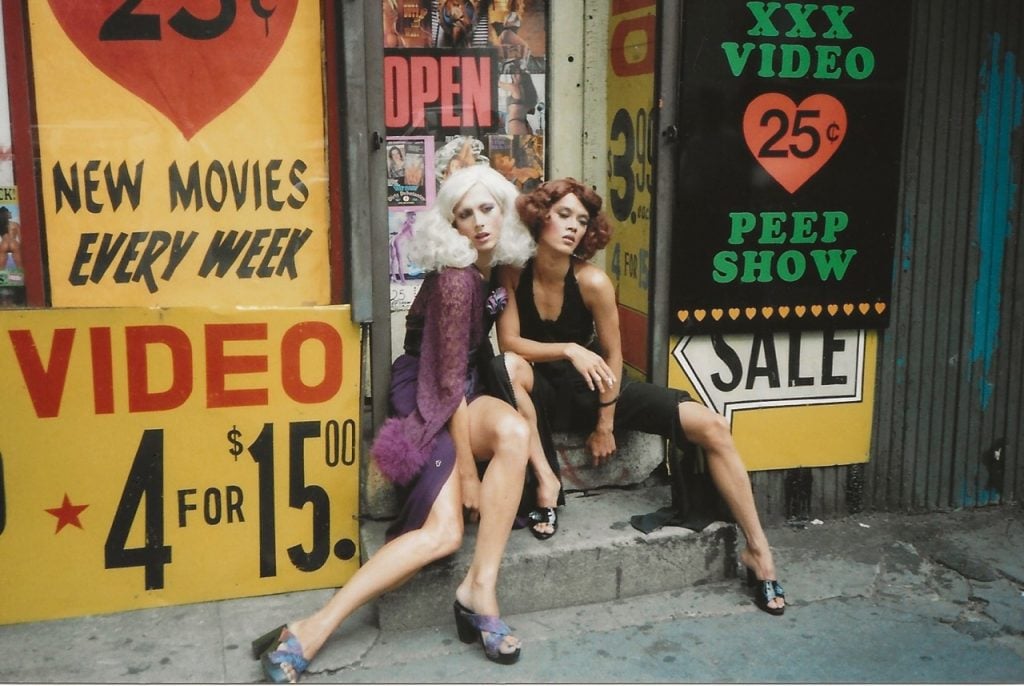

Mark Viera, Sylvester (1979). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

“It sounds cliché, but visibility is very important,” Miller said. “Even in art school, it wasn’t like it is now—they were bullying us. They would yell and throw things at us. One guy even tried to push me down the stairs. The more visible we are, the more people grow up not thinking we’re an oddity.” The exhibition has the scale and star power of established international art events, yet it is marked by a decidedly Detroit DIY punk spirit and attitude. Burton was inspired by the social, political, and artistic dynamics of the Harlem Renaissance. “Not only was it a movement that was affirming for a community, but also that there was this kind of art as activism, really challenging a white perspective, that forced the greater society to see the genius and brilliance of black people through their art,” he explained. “I always thought that this was a great model for us. This period we’re living in is a queer renaissance.”

John Criscitello, Old Glory (2021). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

In addition to this explosion of queer visual art, there is an excellent month of programming, with events that focus on sharing the lesser-known queer histories of country music and techno, as well as tours of 80’s and 90’s drag, led by beloved artists such as drag impresario Linda Simpson and poet Pamela Sneed. In addition, there is a documentary series curated by filmmaker/sex party organizer Adam Baran.

As I entered the opening night party at Menjo’s, a classic Detroit gay bar 20 minutes by car outside the city center, that offers both a dance floor and a pool table, a sexy butch Black lesbian rushed by me wearing a T-shirt that could have been a text piece in the exhibition. It posed the question: “Who ate all the pussy?” As we mingled with the bar regulars, while an Ariana Grande remix played, I declined an invitation to compete in the sexy underwear competition. Instead, I shared a drink with the Spanish, New York-based artist Silvia Prada, whose drawings are haphazardly installed at Kayrod gallery. She told me she thought “the Biennial needs more love” but then softened her critique adding, “I wanted to buy so many pieces, I almost turned from artist to collector.”

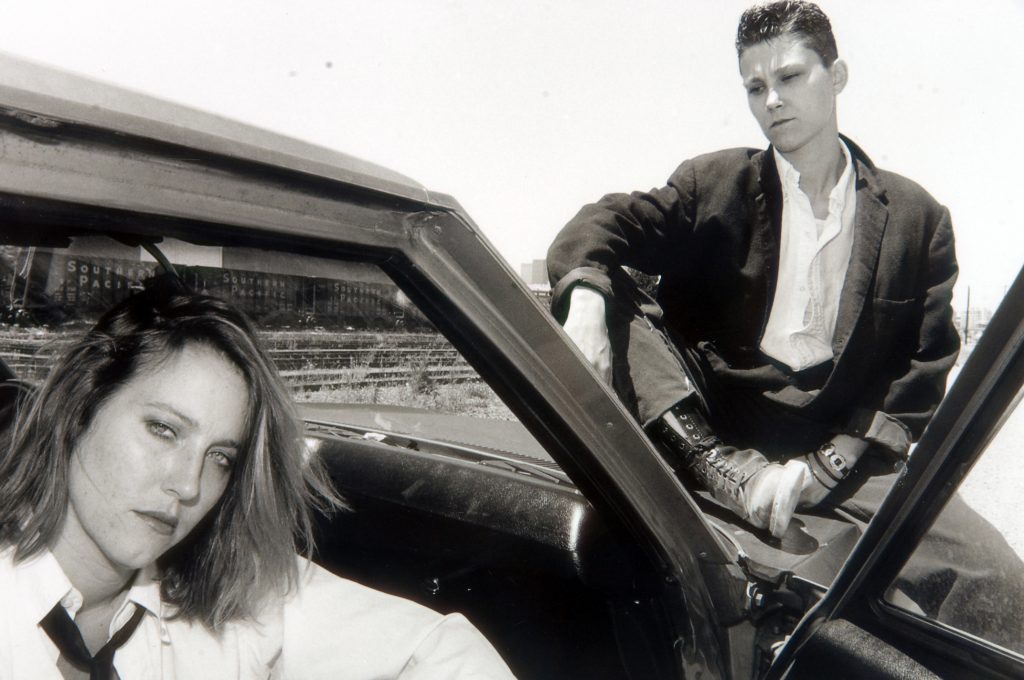

Leon Mostovoy, Baby You Can Drive My Car, San Francisco (1992). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

The festival’s grassroots origins manifested in ways that have both strong advantages and some drawbacks. This project was born out of a shared lived culture, outside of academia and any other institutions. Daniel Trese, a photographer who is included in the exhibition, a native Detroiter who is currently based in New York, offered his take: “Motown wasn’t built in Hollywood or New York, it was built here because there nothing to fucking do and there’s no money. People just have to do shit for themselves. That’s why punk, techno, and Motown all happened here. It makes sense to start a queer biennial here. Also, because it’s not some famous curator, that allows for a new approach.”

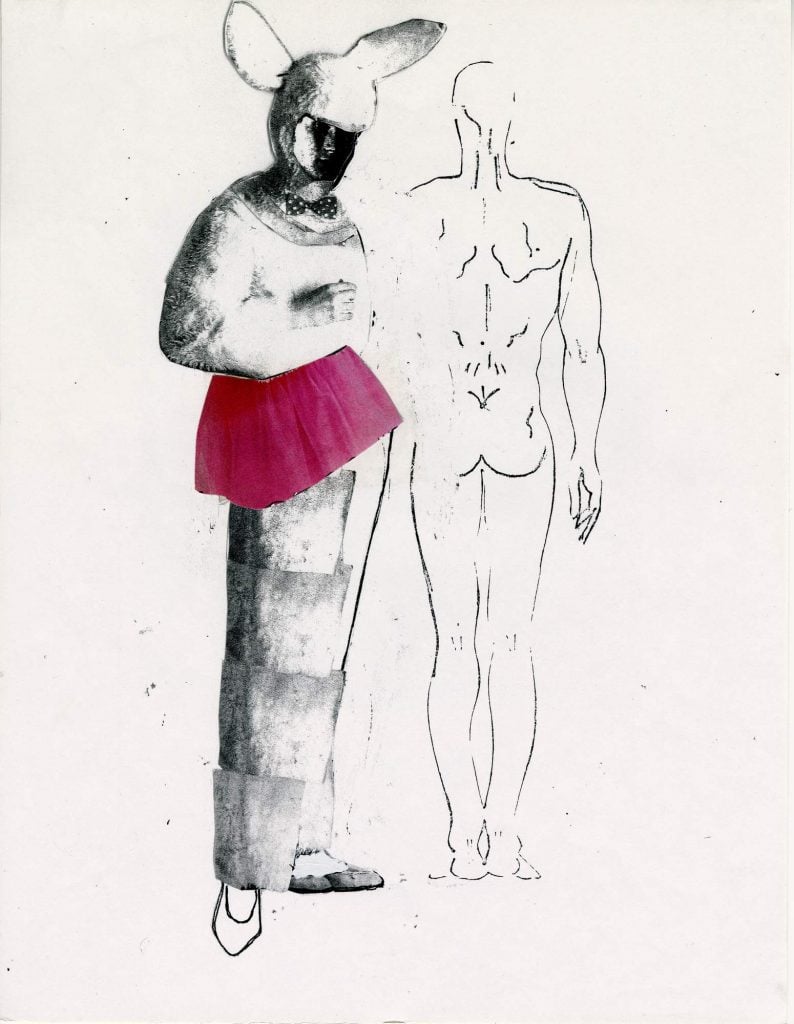

Frederick Weston, Easter Parade (2012). Courtesy Frederick Weston Estate and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

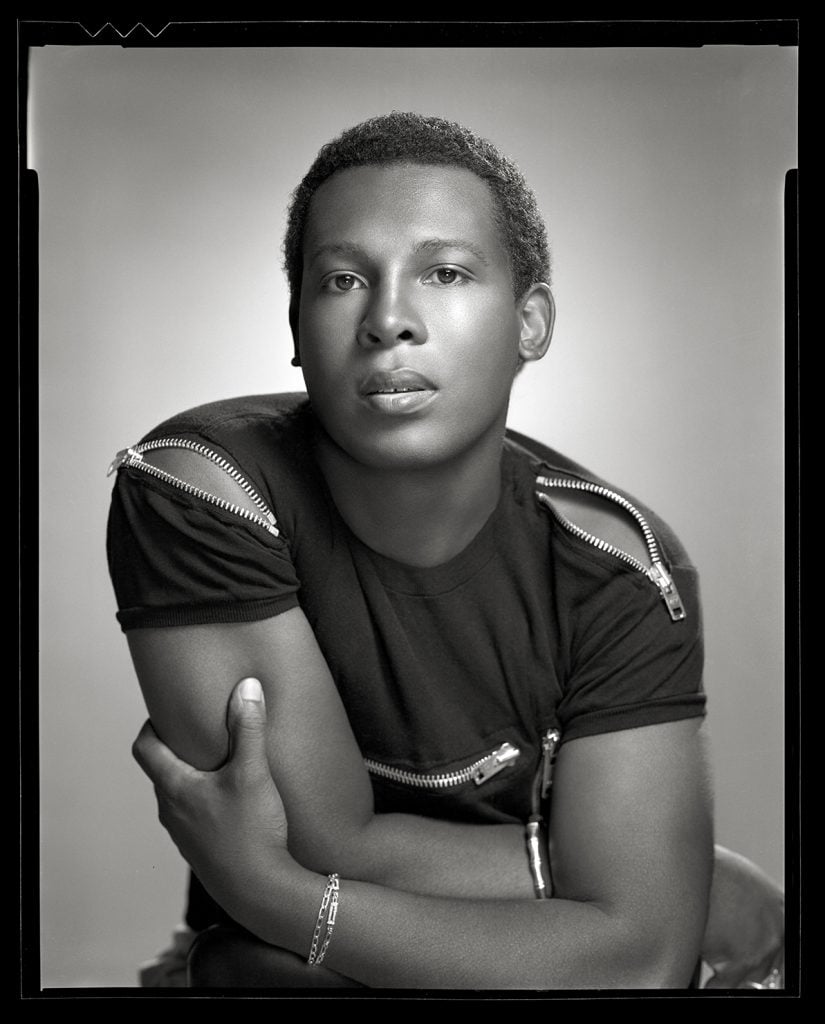

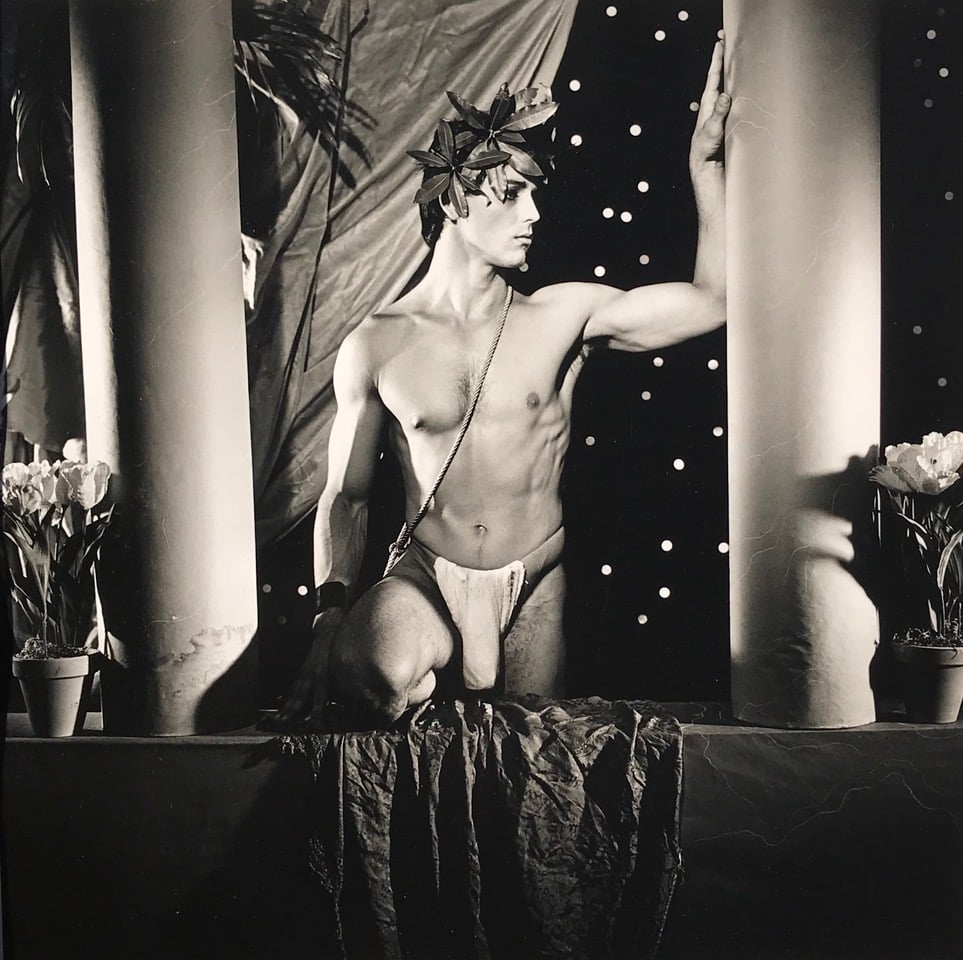

Burton’s democratic edit honors artists at every point in their career. Younger artists have been placed in dialogue with established stars like Peter McGough and Frederick Weston. Formative historical photographs, such as Alvin Baltrop 1970s’ photographs of flirting marines, Steven Arnold’s 1980s’ depictions of over-the-top, mystical heroes, and Wilhelm von Gloeden’s 1900s’ images of Sicilian boys wearing nothing but crowns of flowers, add context and lineage. The show also has a very strong NYC presence featuring talents such as: Felix Beaudry, Liz Collins, Thomas Dozol, Benjamin Fredrickson, Matt Keegan, Paul Kopkau, and A.L.Steiner. The 11 venues hosting the event range in style from traditional galleries to community centers and revamped police precincts. The unique character of these locations adds a layer of local flavor. Visiting one after another transforms Detroit into one big gay-art scavenger hunt.

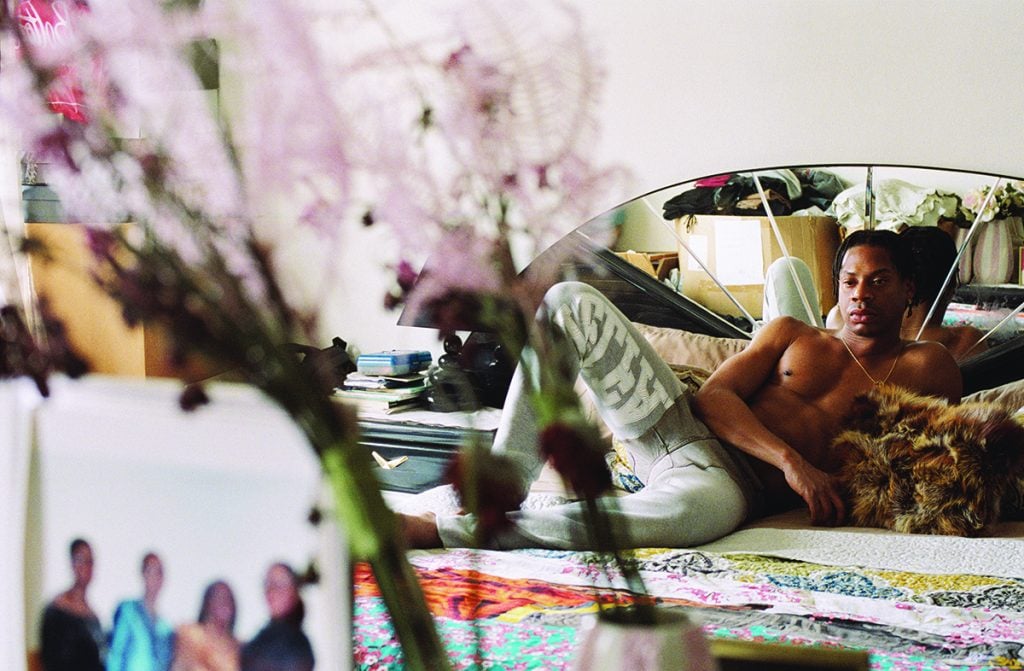

Benjamin Fredrickson, Telfar Clemens (2019). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

While I’m sympathetic to the proportion of funding versus the enormous scale of this pioneering project (the exhibition was organized by a mostly volunteer staff with 80% of the resources going directly to shipping artwork), the drawbacks of this DIY approach are felt in the details. The installation skill level varied from venue to venue with no consistent standard, which sometimes left brilliant works looking amateur. More impactful than this was the lack of conceptual organization, with groupings mostly feeling more focused on solving the puzzle of how to present the vast scope of work, rather than on pairing like-minded ideas, politics, periods, or regional movements that felt synergistic. Jan Wandrag, an artist based in New York felt that this exhibition was more about being together. “Our community is getting so diluted,” he said. “So, it’s great to spend a whole weekend with other queer artists. It’s more about interacting with each other than what’s on the walls.”

Steven Arnold, Confidante of the King (1982). Courtesy of Wessel + O’Connor Fine Art.

As I walk into the first exhibition at the historic Scarab Club, one of Michigan’s oldest arts organization. Its ceiling beams have been signed by more than 230 artists. While spotting the signatures of Marcel Duchamp, Diego Rivera, and Norman Rockwell, a prominent painter and critic mentioned to me, “Simplistic ideas about identity drive too much queer art these days.” This thought frames my perception and inspires more questions. Is there a need to segregate queer artists to their own spaces? And in fact, haven’t LGBTQ+ artists fought to have their work viewed as simply “art” and not “gay art”? And if the current malleable definition of queer is someone who celebrates and articulates their differences from mainstream society, couldn’t all artists be considered queer?

David Greene, Tea Time – Three Revolutionaries (1974). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

These questions are not unique to this biennial; they reflect trends seen at the highest levels of the art world. In this year’s Venice Biennale, “Foreigners Everywhere,” the focus was on showcasing queer and BIPOC artists. (Artist Anish Kapoor decried the Biennale’s title as echoing the language of nationalist neo-fascism.) The Whitney Biennial “Even Better Than the Real Thing” combined asexual ennui with its do goody institutional progressivism. As art institutions push to elevate minority voices, isn’t isolating their work to queer contexts only unintentionally further marginalizing queer artists?

Alyssa Nitchun, the director of New York’s Leslie Lohman Museum, was invited to speak on panel discussion had a more generous perspective. “It’s wonderful to see initiatives supporting queer art and artists taking place outside the usual epicenters of New York and LA, where there are traditionally fewer frameworks in place for exhibiting queer art,” she said.

Joe Ovelman, Marine Corps Uniform 1970. Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

Inside the Scarab Club, the intergenerational conversation between photographers works exceptionally well. The exhibition starts with Pennsylvania-based artist Joe Ovelman, showing a portion of “Marine Corps Uniform 1970,” a series of black and white portraits of sexually ambiguous military men. The artist revealed later, that they were all strangers he had approached on the gay beach in Miami in the late 90s and asked if they would be photographed wearing his father’s service uniform. These works hung next to work by George Platt Lynes (the subject of the recent documentary Hidden Master). His elegant black-and-white portraits are staged utilizing his beloved flamboyant minimalist, theater queen dramatics. Carl Van Vechten’s straight forward emotional portraits of 1950s-era butch luminaries like Geoffrey Holder and Joe Louis convey a range of moods from confident to contemplative. The New York-based artist Jeannette Spicer’s inventive color photos showcase tightly cropped naked female forms, using bodies to frame bodies, are minimal and mysterious. Her women become abstracted into lines and curves. These four artists, with work ranging from almost a century apart, felt connected as a family of thought.

In these vastly different time periods slightly different versions of the same questions remain. How can each artist honor and historicize the glory, talent and beauty of their subjects, in new innovative ways that make the world around them care about, respect and desire queer people. How do we share the best of ourselves in way that can be undeniably felt?

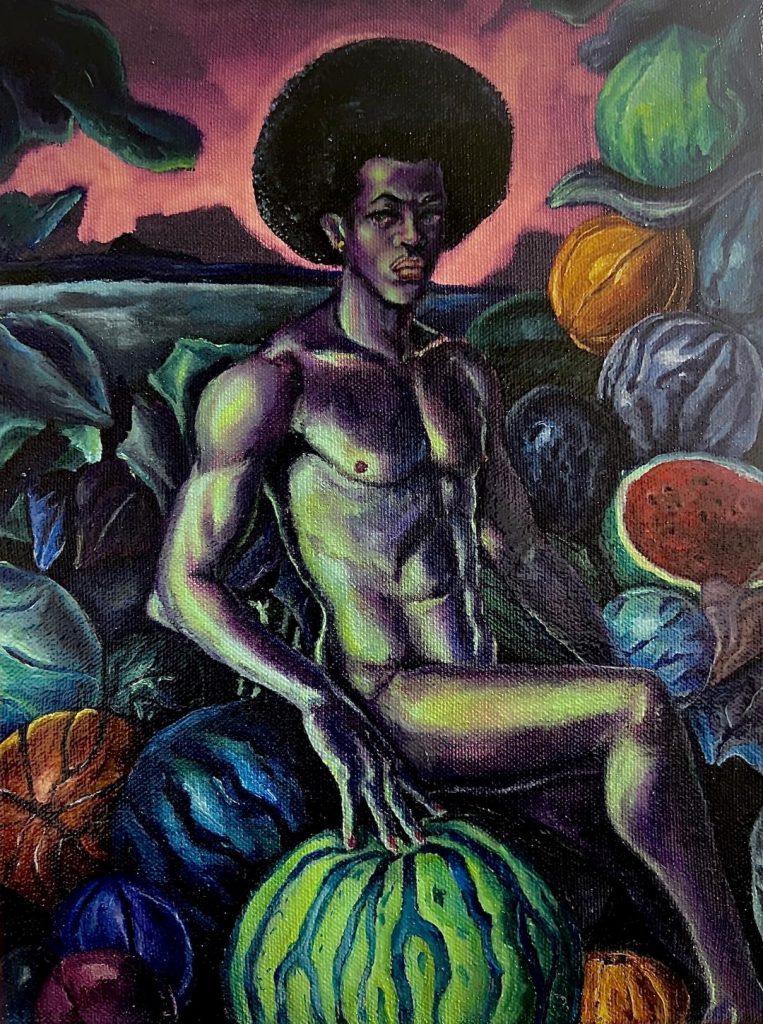

Anthony Peyton, Fruits of Our Labor (Night Version) (2024). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

With over 180 artists in the show, the sense of discovery was inspiring even for the most seasoned queer art aficionado. I was thrilled to be introduced to the work of so many accomplished artists I had never heard of. LeRoy Foster (1925-1993), whom locals dubbed the Michelangelo of Detroit was an openly gay Black figurative painter who was in his prime in the 1950s. He was never included in a major art exhibition during his lifetime. Although he was locally famous for his masterful homoerotic mural Renaissance City, commissioned for a local high school, and his equally spicy depiction of Frederick Douglas in a mural for the Detroit Public Library. This exhibit features previously undiscovered works by Foster’s drag persona, Marti Marti. The cartoon Lil Joe Gentry, Why Won’t You Marry Miss Foster (1945) shows a frustrated woman scolding a dapper, happy, well-dressed bachelor. It’s hard to for me to understand why this accomplished contemporary of Tom of Finland is not nationally recognized as a pioneering LGBTQ+ artist.

Howard Kottler (1930-1989) was a ceramist who received his MFA from Cranbrook in 1954. He is best known for his decal plates, which rejected traditional studio ceramic practices. Kottler’s conceptual ceramics utilized coded images, biting humor, and wordplay. His piece titled Look Alikes (1972), is a porcelain plate that queerifies the iconic American Gothic—the female figure is replaced by a duplicate of the male.

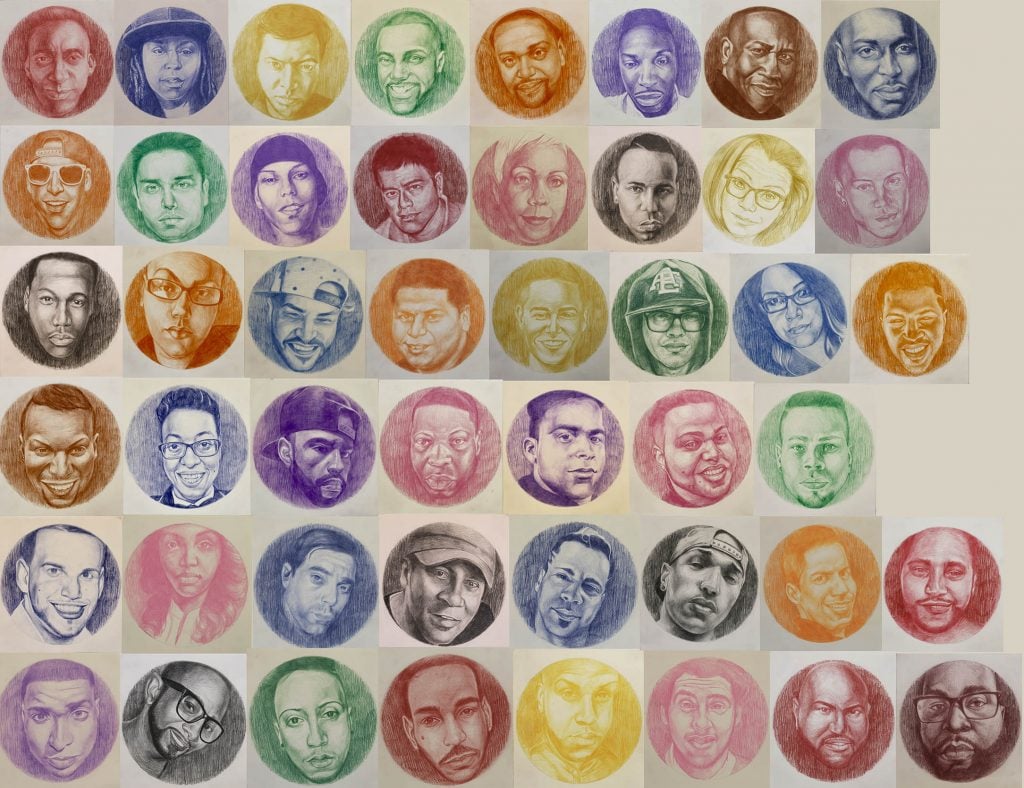

Tylonn Sawyer, Forever Young: Pulse Nightclub 49 (2024). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

Tylonn Sawyer presents a stoic and poignant memorial, consisting of 49 multicolored monochromatic realistically rendered colored pencil drawings, each depicting a victim of the Pulse Nightclub massacre. His work, titled Forever Young: Pulse Night Club 49 (2024), serves as a meaningful tribute to the lives lost in this tragic event, capturing the individuality and spirit of each person in a respectful and moving manner.

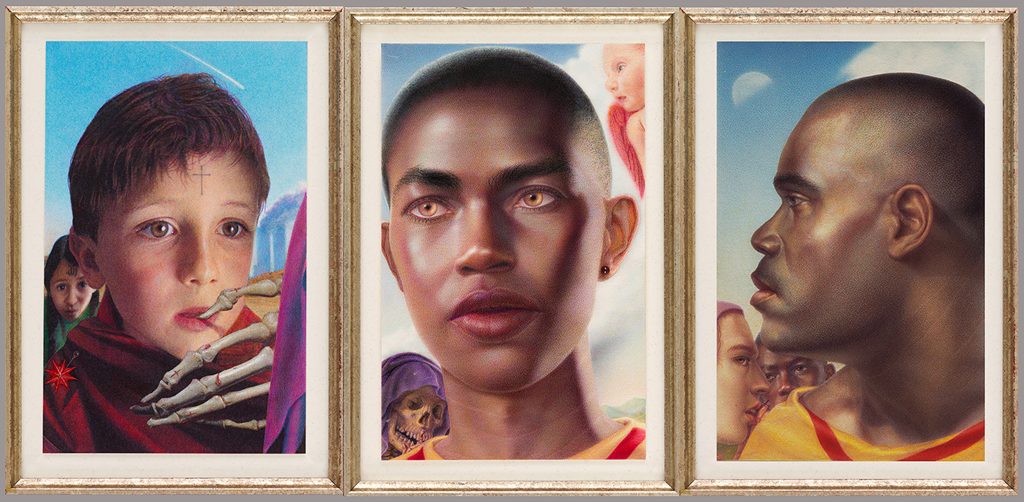

Carl Demeulenaere received his MFA in 1981 from Wayne State University. The composition of his detailed, hyper-color jewel-like works feel inspired by early Italian Renaissance portraits. In this show, he presents Arcadia Triptych (2006-2008), a series of close-up portraits in which two of the three subjects are confronted by the Grim Reaper. These technically masterful, eerie small-scale works are made with colored pencil, acrylic, linen, garnet, and blood.

After enjoying two days of “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” I wondered how much of a straight audience could be attracted to a queer biennial? Are straight people interested in seeing their reflection through the eyes of the queer community? Is a queer art show just a bunch of gay preachers enjoying themselves as they preach to gay choirs? Omo Misha, co-founder of the Irwin House Global Arts Center and Gallery, was giving a tour of the space. We talked as she shared three incredible Doug Johnson paintings (irregular canvas in the shape of bulging steroid sized arms, that frame somber fantasy landscapes.

Carl Demeulenaere, Arcadia Triptych (2006-2008). Courtesy of Mighty Real / Queer Detroit.

“And what this exhibition and many of the exhibitions show us,” Misha explained, “is that queer people, like everybody, are thinking about the things and the issues that affect them as queer people, but they’re also thinking about everything else. They’re thinking about nature, dogs, friends, and falling in and out of love. This exhibition really shows us how much more alike we all are. We have had all kinds of people here today.”

“So, you’re finding that straight audiences don’t need the artist to share their sexual orientation to engage with art work?” I asked more directly.

Misha replied, “I won’t say that’s not true. People do want to see themselves reflected in art, but they are also open to seeing themselves reflected in someone else. People just want to see beautiful art. Who wouldn’t be wowed by Johnson’s paintings? Nobody…everybody?”