“Liberty/Libertà” is the title of Martin Puryear’s exhibition for the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year, which officially opens today. The name anticipates the political reading that is inevitable in this show about national representation at a time when that subject is particularly fraught, and it contains many charged historical references, particularly to Black political history. But just what exactly the show says is not so clear, or rather very carefully unclear.

In fact, you could take “Liberty” to mean liberty from blunt-force meaning—a sensibility characteristic of the 77-year-old sculptor, known above all for his eloquent use of materials and elliptical gravitas. Despite the scale of a few of the works here, “Liberty” is a stately and understated show, speaking riddles in an even voice rather than shouting its opinion at full festival volume.

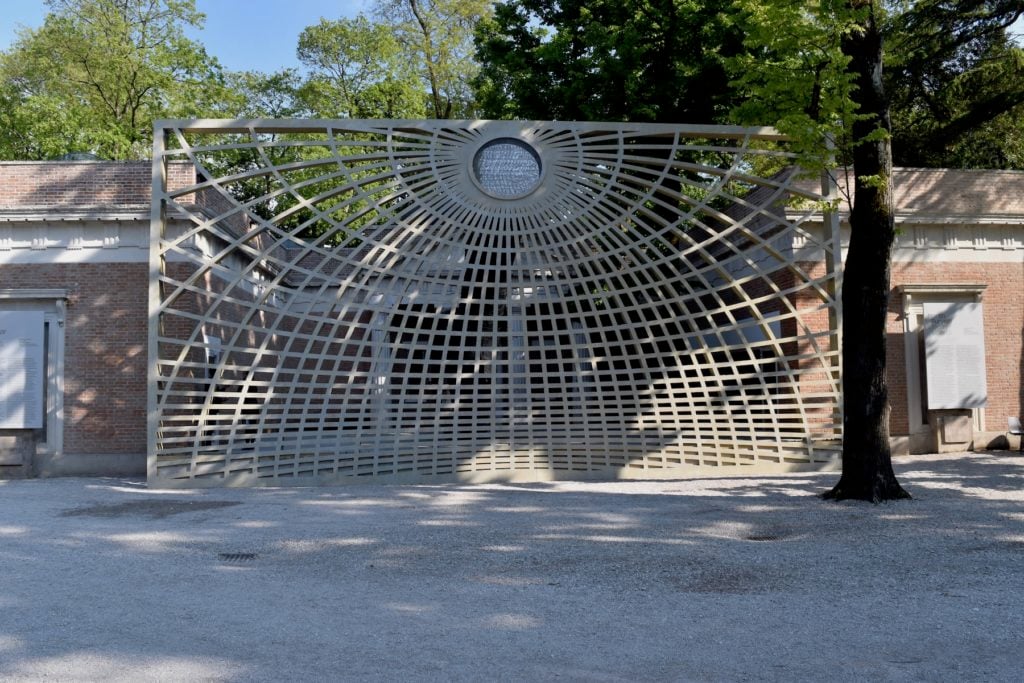

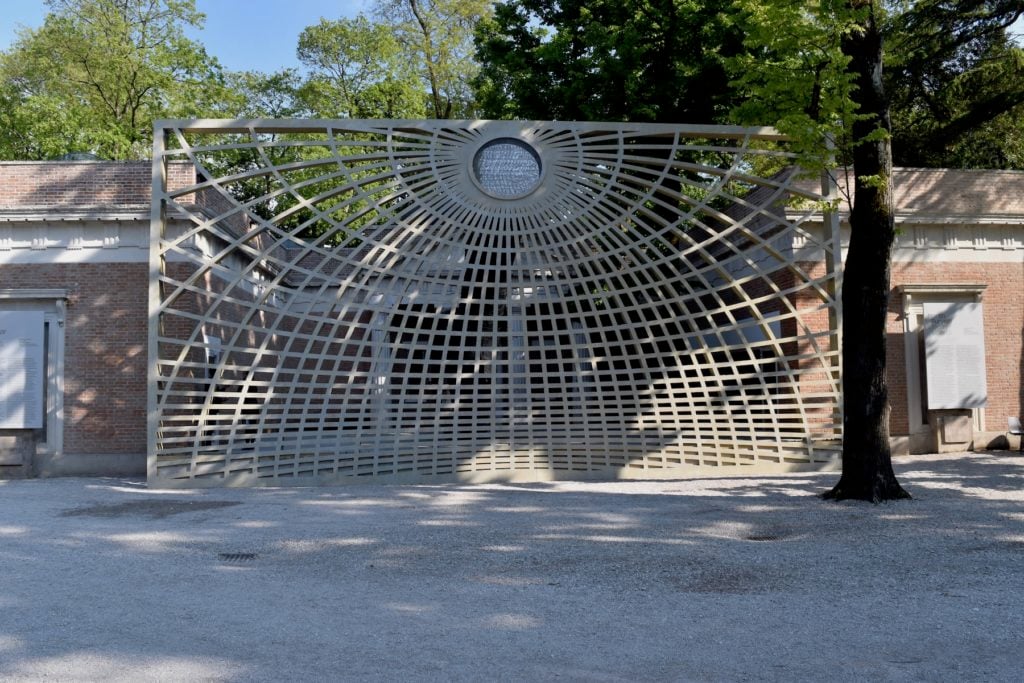

Even Puryear’s biggest work, Swallowed Sun (Monstrance and Volute), has a strangely obtuse quality. Consisting partly of a large wooden screen sited in front of the pavilion’s courtyard, it is architectural in scale (it is in fact a collaboration with Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects), rising above the building. But its muted sandy color and flat plane make it seem almost, on first brush, more like a privacy curtain sheltering the pavilion than a sculptural statement in its own right.

Martin Puryear’s art installed at the US Pavilion in Venice. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Stepping around it into the courtyard, you encounter a black spiral form blooming up from the earth to join into the screen—as if Puryear were stating right at the front that you have to penetrate the surface to get to the dynamic guts of the show.

Martin Puryear’s Swallowed Sun (Monstrance and Volute) (2019) at the US Pavilion in Venice, 2019. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The spiral is an old symbol of the movement of history, and uneasy, unsettled historical references abound beneath the thoughtful surfaces of “Liberty.” The show is centered on A Column for Sally Hemings, named after Thomas Jefferson’s slave-turned-mistress. Since the pavilion itself is inspired by the architecture of Jefferson’s Monticello, the symbolism of the vaguely anthropomorphic column—it resembles a woman in a dress if you squint—seems clear enough: a tribute to a forgotten protagonist manifesting out of the background of history, a ghost haunting the architecture of US representation here in Venice.

Martin Puryear, A Column for Sally Hemings (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

But there’s not really one history or story in “Liberty,” just riffs and echoes and loose thoughts (most of the works were already in production when the Madison Park Conservancy successfully pitched Puryear as the US representative for Venice). Big Phrygian (2010–14), located in one wing of the pavilion, is a giant-sized sculptural version on the cap that became a symbol of the French Revolution, and that stands on the coat of arms of Haiti, symbolizing that nation’s foundation by freed slaves.

Martin Puryear, Big Phrygian (2019-2014). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Opposite it, in the other wing, Tabernacle is a similarly scaled sculpture that is inspired by an American Civil War soldier’s cap. You can gaze into a kind of window into it, and see, cradled within, something that resembles a mortar—unexploded ordinance that history has not fully dealt with.

Visitors interact with Martin Puryear, Tabernacle (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

But the thing to stress with Puryear is that these are sculptural objects: they evoke references without reducing to them; the accent is on material and the odd, specific forms, with the historical inspiration just laying latently within (like that mortar).

Martin Puryear, Tabernacle (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

If you were to take the cap reference of Big Phrygian or Tabernacle literally, they would make you feel small, a tiny figure staring at inexplicable artifacts left behind by a history that dwarfs you. But elsewhere, a work like Cloister-Redoubt or Cloistered Doubt? reverses that play with scale.

That piece offers an open, peaked structure, sheltering a sturdy carved wood box that echoes the slouched form of the various caps here, perched atop a tower of stacked logs. Instead of something small turned giant, it evokes some kind of abstracted religious architecture, reduced into a sculptural shrine.

Martin Puryear, Cloister-Redoubt or Cloistered Doubt? (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

In New Voortrekker, a sculptural wooden wagon seems to trundle its way up a slope. The incline it ascends is a board, perched atop a ball, so that it looks designed to collapse beneath it if the wagon were to proceed too much farther. The title contains the word “pioneer” in Dutch; it references the “Great Trek” of Dutch-speaking settlers from British-ruled South Africa, an event that falls chronologically between the French Revolution and American Civil War. The migration of white settlers was a major event in the colonial history of the African continent, a powerful symbol for the architects of the racist Apartheid system a century later.

Martin Puryear, New Voortrekker (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Compared to Puryear’s giant hats, here the scale is reversed. Here you are the giant, and history is your toy. But the shifts in scale in “Liberty” overall say that the sculptures are meant neither to reduce history down to a neat statement, nor to blow it up into the unthinkable. It just flows uneasily through the sculptures, part of the material they are made of, as inseparable from them as wood or steel.