Law & Politics

A Showdown Over Pricey Western Artworks That Went Missing Decades Ago Heats Up in Court

The paintings went missing more than 50 years ago.

The paintings went missing more than 50 years ago.

Eileen Kinsella

A legal battle is heating up over several valuable paintings by Western artists that went missing from a prominent private collection decades ago. One turned up on an auction block in Los Angeles last fall and a showdown has ensued ever since.

Heirs of the original owner had flagged a painting by Eanger Irving Couse on the L.A. auction block as one of a larger group that went missing at least as far back as the 1960s. However, they were sued by a high-profile dealer who sought “quiet title” to the work.

His gallery asserts several points, including that the painting was never reported stolen to the proper authorities; the statute of limitations for a claim had expired; and that all known sales and ownership transfers in subsequent years were done in good faith.

Now, the heirs have fired back with counterclaims of their own, outlining in detail the chronology of their family ownership, how and when the artworks disappeared, and why they are entitled to their return. They have also expanded their claim to include several other missing artworks that ended up in the collection of the accused dealer.

Image via Bonhams.com

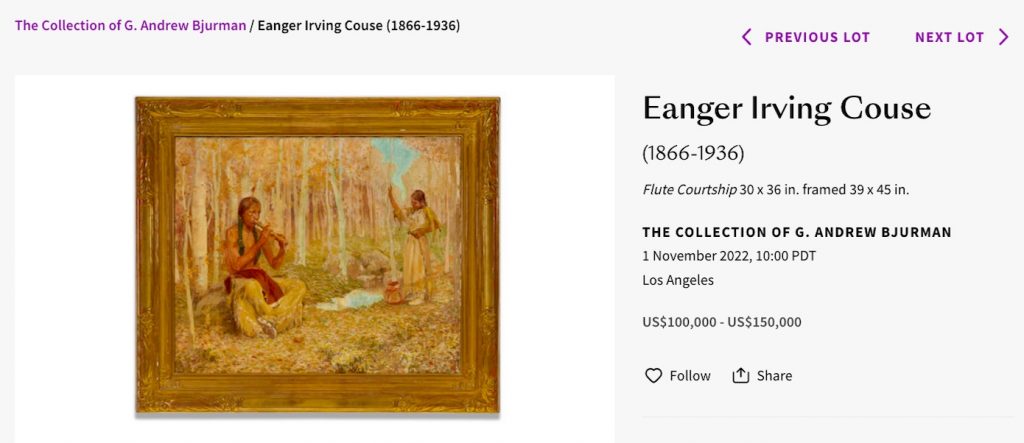

The saga started last fall when Bonhams auction house in Los Angeles offered Flute Courtship, Couse’s circa 1906 depiction of two Native Americans, one seated and playing the flute and another standing farther back in the distance, from the collection of G. Andrew Bjurman, with an estimate of $100,000 to $150,000. According to the Artnet Price Database, the work was “bought in,” or went unsold.

That auction caught the eye of heirs Joan Weiant and Leigh Brenza, who saw the painting and demanded “surrender of possession” from the auction house. That prompted a lawsuit from high-profile Western art specialist Gerald Peters Gallery, which operates galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and New York City.

The attorney for Weiant and Brenza declined to comment. Attorneys for Gerald Peters Gallery did not respond to request for comment. Bonhams did not immediately respond to request for comment.

“This action concerns a belated assertion of title to Flute Courtship, a painting by New Mexico painter Eanger Irving Couse by Joan Weiant and Leigh Brenza, the heirs of Lindley and Charles Eberstadt and purported successors-in-interest to the firm of Eberstadt & Sons,” according to Peters’s complaint.

According to the complaint, the “issue raised is solely whether the defendants’ claims are barred by the passage of time under the doctrine of laches and the statute of limitations.”

The Peters complaint asserts that the gallery “is prepared to have all the factual and legal issues surrounding the claim to the painting resolved by the court,” adding that the ownership claim is “without merit.”

The case was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York earlier this year and amended at least twice, most recently in September. Among the key arguments it puts forth: after a group of paintings were entrusted to a New York framing and restoration company known as Shar-Sisto by the Eberhardts, approximately 17 works were unreturned despite requests from the family and, later, their heirs.

Peters’s complaint stated that “no one ever reported any of the unreturned artworks as having been stolen to any police department, the FBI, or Interpol.”

However, the gallery acknowledged that someone affiliated with Eberhardt & Sons reported the unreturned artworks as missing to the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) in 1974, 10 years after Eberhardt entrusted them to Shar-Sisto. ADAA circulated a typewritten notice to member galleries of the ADAA on November 6, 1974, listing artworks reported to it as missing. The notice included an entry for “E.I. Couse Indian Courtship,” which defendants claim to be the painting at issue in this case under a different title, according to the complaint.

The gallery, which bought and sold the painting, points out that it has never been a member of ADAA, nor did it ever see a copy of the ADAA notice, “which in any event had very limited dissemination in New York City and almost none outside major American cities.” It adds that no one alerted the New York-based International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) of the alleged theft.

The complaint said that in November 1993 or December 1994, the New Mexico branch of the Gerald Peters gallery “was the successful bidder at the Texas Art Gallery, a reputable Dallas auction house, of a work of art by Irving Couse there titled The Flute Courtship. It paid $63,450 for the work.”

The gallery also noted it loaned the painting to at least two high-profile museum shows, one at the Palm Springs Desert Museum and another at the National Wildlife Art Museum in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, both in 1995. “Both of these exhibitions attracted large audiences and significant publicity,” according to the complaint.

The following year, the gallery sold the painting to Bjurman, who passed away in April 2022. Bjurman’s heirs, via a trust, consigned it to Bonhams for the 2022 auction.

The record for a work by Couse at auction is $937,000. The popular painter, who had a lifelong fascination with Native Americans and their culture and way of life, was also a founding member of the Taos Society of Artists, and its first president.

Now, Weiant and Brenza have fired back at the Peters lawsuit with counterclaims that, not surprisingly, tell a very different story.

According to their 13-page complaint, filed November 20, Edward Eberstadt founded Eberstadt & Sons as a bookselling business in New York City in the early 20th century. In or around the mid-1960s, Eberstadt & Sons wanted assistance with its art collection concerning cleaning, restoration, reframing, and other conservation services.

That’s when they turned to Shar-Sisto, and the two agreed that the firm would perform this large volume of work as time permitted, with no firm deadline. They also agreed that Shar-Sisto would hold the paintings after work was completed so that they could be photographed. Approximately 77 paintings were handed over to Shar-Sisto.

Around 1970, the majority of the paintings were returned to the Eberstadts at the family’s request and in anticipation of a planned sale.

“But Shar-Sisto failed to return at least 17 paintings from the collection… When Lindley Eberstadt inquired about them, Shar-Sisto personnel assured him that that these paintings were located at Shar-Sisto’s facilities but that they needed more time to assemble and return them. Eventually, though, Shar-Sisto never returned the missing works, including the Couse at issue in plaintiff’s suit here,” according to the counterclaim.

In the early 1970s the Eberstadts contacted ADAA about the stolen works. Shortly after, court papers stated, the ADAA turned over its database to IFAR, whose resources eventually formed the origin of the Art Loss Register (ALR), which today is the largest private database on lost and stolen art.

Charles Eberstadt died in 1974, and Lindley Eberstadt in 1984. Eberstadt & Sons was dissolved around 1975. “While some of the business’s remaining art, documents, and manuscripts were sold, no rights in any of the artworks from the theft notice were sold to anyone,” according to the counterclaim.

In addition to the Couse, the counterclaim asserted “extensive links between the missing Eberstadt artworks and Gerald Peters.”

While the heirs said that for many years they had no leads as to the whereabouts of the missing works, more recently, the family “learned that Gerald Peters and his gallery have documented links, going back to the early 1980s, to a number of the missing Eberstadt artworks, all of which were apparently being sold or exhibited under different titles than those by which the Eberstadt family knew them.”

They include a work by artist John Mulvany that appeared at an auction under the title Trappers of the Yellowstone, but which the family knew and reported in the theft notice as Awaiting the Claim Jumpers.

“Gerald Peters was in possession of the Mulvany as early as 1982, when the Gerald Peters Gallery sold it to the buyer who eventually returned it to the Eberstadt family… The Eberstadt family secured the Mulvany in 2019,” according to the counterclaim.

The counterclaim continues that in 1982, Peters loaned a number of artworks to an exhibition in Houston, Texas—including a missing Eberstadt artwork by painter Alfred Jacob Miller. “The 1982 exhibition catalogue, titled Art of the American West, documented the Miller under a different title than what was listed the theft notice,” the papers stated.

The counterclaim noted that Gerald Peters’s collection was also the subject of a 1988 book, The West Explored: The Gerald Peters Collection of Western American Art, by Julie Schimmel. “That book included images of at least three missing Eberstadt artworks: the Miller, as well as a work by artist Paul Kane and a work by artist J. A. Woodside.” All were published under different titles.

Lastly, in 1988, “yet another missing Eberstadt artwork, this one by artist Frederic Remington was offered at auction at Sotheby’s. In the auction documentation, Sotheby’s listed ‘Gerald P. Peters, Santa Fe’; in the Remington’s provenance, and referred to the Remington by a different title than was reflected in the theft notice.”

The Eberstadt heirs demanded the return of the Couse painting in March 2023. This past month, they demanded the return of the additional specified missing works, adding in the Remington, the Miller, the Kane, and the Woodside to the previously requested Couse painting.

“To date, Gerald Peters and the Gerald Peters Gallery have refused to return any of those missing artworks,” according to the court papers.

More Trending Stories:

A Shipwreck Off the Coast of Colombia May Hold $20 Billion Worth of Treasure

Hot! How a Backyard Photographer Captured Some of the Most Detailed Images of the Sun

Chinese Artist Chen Ke Celebrates the Women of Bauhaus in a Colorful, Mixed-Media Paris Debut

A Centuries-Spanning Exhibition Investigates the Age-Old Lure of Money

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece