Archaeology & History

A.I. Is Helping Scholars Decipher the Epic of Gilgamesh

The project is called the Framentarium.

The Epic of Gilgamesh: It’s a tale some 4,000 years old, passed down only in an extinct writing system of wedge-shaped characters on fragments of clay tablets. And now, scholars are deciphering previously unknown parts of the story thanks to the power of A.I. cuneiform translation.

The project is called the Fragmentarium, and it runs on an algorithm developed by a team at the Institute for Assyriology at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, Germany.

“It’s a tool that didn’t exist before, a huge database of fragments. We believe it can play a vital role in reconstructing Babylonian literature, allowing us to make much faster progress,” Institute of Assyriology professor Enrique Jiménez told science news outlet Phys.

For thousands of years, the cuneiform writing on clay tablets from the Babylonian era remained a undecipherable mystery. It was a British Museum employee named George Smith who in 1872 became the first modern scholar to read the Epic of Gilgamesh. He died just four years later, at age 36, on a journey to the Middle East in search of more pieces of the lost poem.

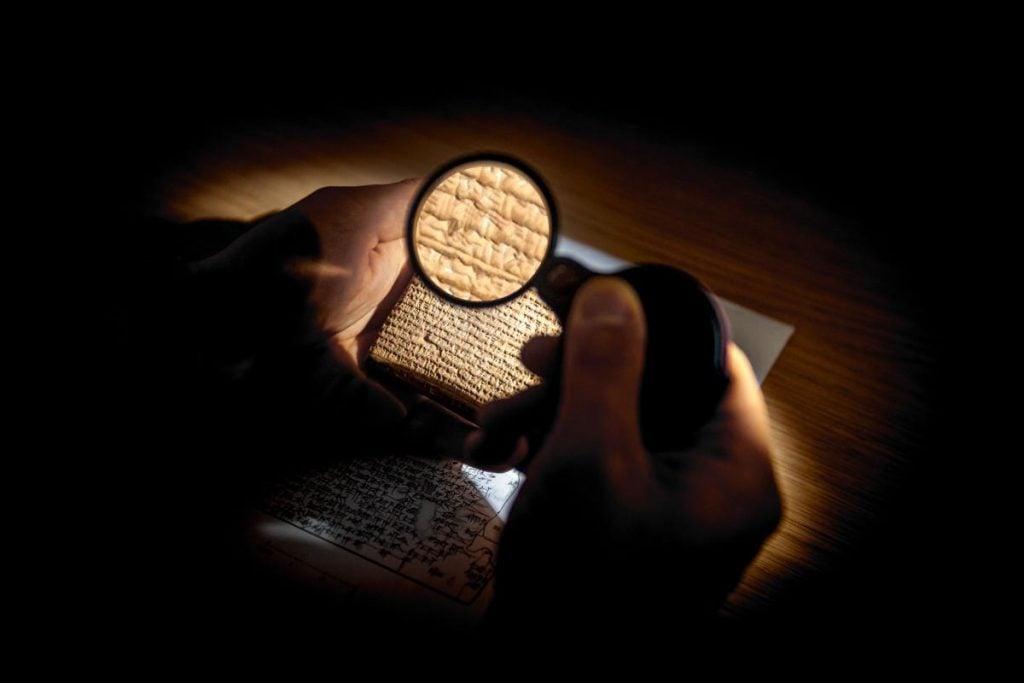

A fragment of a clay tablet with cuneiform text. Photo courtesy of Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Germany.

Scholars have spent over 150 years following in Smith’s footsteps. Piece by piece, the story has come together as archaeologists have unearthed new cuneiform texts during excavations, museum workers have rediscovered dusty fragments forgotten in storage, and authorities have seized looted artifacts.

But in recent years, A.I. has given a major boost to their efforts. The Fragmentarium can work much faster than a human Assyriologist to translate these age-old texts from the original Sumerian and Akkadian.

Not only can this help identify missing sections of the poem, it can translate all manner of ancient Babylonian writing. Some of these surviving texts can seem mundane, but even bills of sales and other everyday records can help broaden our understanding of this ancient civilization.

Since 2018, Fragmentarium has matched lines from the epic to text from 1,500 tablet fragments. Before A.I. was put to the task, scholars had only done so for about 5,000 pieces.

“The traditional process is based on the researchers’ good memory and, of course, on the principle of chance,” Jiménez said in a statement. “The modern, A.I.-based reconstruction process, on the other hand, relies on researchers’ databases that collect thousands of characters. With the help of artificial intelligence, all known variants of a Babylonian text can be quickly analyzed and used appropriately.”

This isn’t the first time that A.I. has helped out with deciphering ancient manuscripts. A team at Tel Aviv University and Ariel University in Israel unveiled a similar project working with Mesopotamian cuneiform in 2023. And an A.I. system from University of Kentucky researchers is helping unveil the text on a cache of scrolls burned during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Institute of Assyriology professor Enrique Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Germany.

The Fragmentarium has partnered with institutions including the British Museum and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad to add their cuneiform collections to the database. As of 2023, when the Fragmentarium went public, there were more than 22,000 fragments digitized.

The epic tells the story of the titular demigod, Gilgamesh the King of Urdu, and his friend Enkidu, the wild man. The two kill the guardian of the forest, the monster Humbaba, and the gods retaliate by killing Enkidu. In his grief, Gilgamesh goes in search of his ancestor Utnapishtim, who survived a flood of biblical proportions, in the hopes of learning the secret of immortality.

Thanks to the Fragmentarium, we now know of several new scenes from the story. There are newly discovered lines where Enkidu tries to convince Gilgamesh not to kill Humbaba. And after they do so, the duo travels to see the god Enlil in the city of Nippur.

The Fragmentarium also identified a much newer tablet containing part of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Dating from 130 B.C.E., the tablet shows that the poem was still being copied and shared thousands of years after its first known appearance.

Some of the newly translated texts offer subtle, yet intriguing variations on the story as it was previously known. In recounting his preparations for the flood, for instance, Utnapishtim told Gilgamesh that he “lavished” the men who built the ark with food and drink.

“We didn’t have the word ‘lavish’ before,” Benjamin R. Foster, an Assyriology professor and Gilgamesh translator at Yale University who worked on the project, told the New York Times. “And to my mind, he’s feeling guilty because he knows all the people who are helping him build the ark are going to be drowned in a few days.”

There is still an estimated 30 percent or so of the poem missing, and experts are still learning more about both the story and Mesopotamian writing more broadly. A.I. now looks to play a major role in that endeavor.

“Everyone will be able to play with the Fragmentarium,” Jiménez said in a statement. “There are thousands of fragments that have not yet been identified.”