Art World

Alice Cooper Just Realized He Got a Warhol Electric Chair 40 Years Ago and Totally Forgot About It

The discovery could be the first major market test of a new Warhol authentication service.

The discovery could be the first major market test of a new Warhol authentication service.

Eileen Kinsella

School’s out for summer, and Alice Cooper’s memory went on vacation—at least when it came to his art collection. Amid a 40-year rock career, the legendary singer apparently forgot all about an Andy Warhol canvas he’s had in storage since it was given to him in 1974.

Soon, the painting will see the light of day again—first in Cooper’s home, and then potentially on the market—thanks to advice from a Los Angeles collector and a San Francisco private dealer.

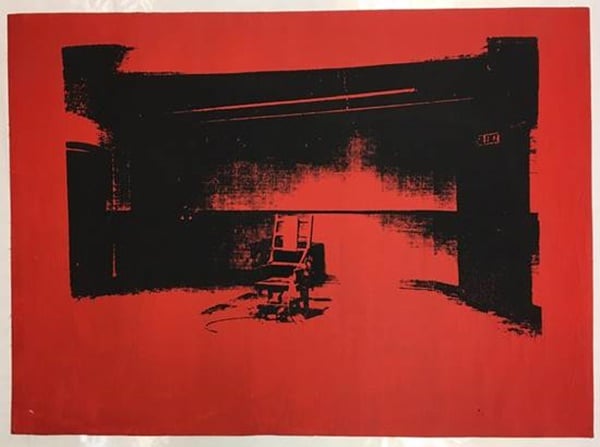

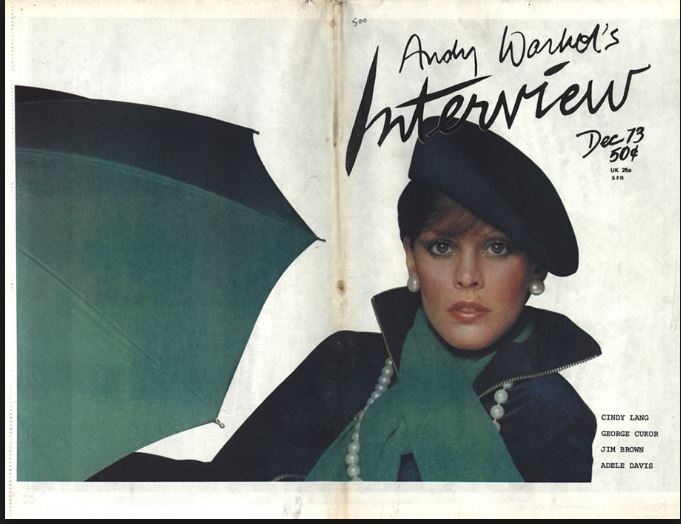

When Cooper was touring during his ’70s heyday, he typically included an unusual theatrical element in his macabre shock rock act: an actual electric chair. Aware of his fondness for the sinister stage prop, Cooper’s then-girlfriend, Cindy Langa—a model who had appeared on the cover of Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine—bought him the Pop artist’s red electric chair silkscreen. She paid $2,500 for it.

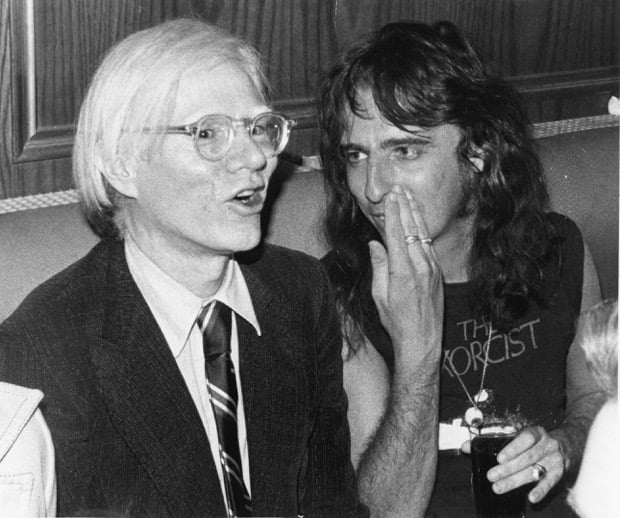

Alice Cooper received this Warhol Little Electric Chair as a birthday gift in 1974. Courtesy Alice Cooper.

“She brought it home to Alice as a birthday present,” Cooper’s longtime business manager Shep Gordon told artnet News. (Gordon is a legend in his own right in music and entertainment circles. He was the subject of a 2014 documentary by Mike Myers titled “Supermensch: The Legend of Shep Gordon.”)

Due to his heavy tour schedule at the time, Cooper rolled up the unstretched work, stuck it in a tube, put it in a temperature-controlled Los Angeles storage facility, and promptly forgot about it for the next few decades. He only remembered it several years ago, over dinner with his friend, the Los Angeles collector Ruth Bloom. Their chat turned to the painting, its whereabouts, and its potential value, according to Gordon.

Cooper was unable to have the work authenticated by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, which shuttered its authentication arm in 2011. (Works that lack a stamp of approval from the foundation tend to struggle to gain traction in the market.)

Interview magazine, 1973. Image via AliceCooperechive.com

In an effort to get the painting checked out another way, Gordon brought it to Richard Polsky, a private dealer, author, and lifelong Andy Warhol fan. (Bloom introduced Polsky to Gordon last fall.) Polsky has been offering his services as an independent authenticator of Warhol’s work since 2015.

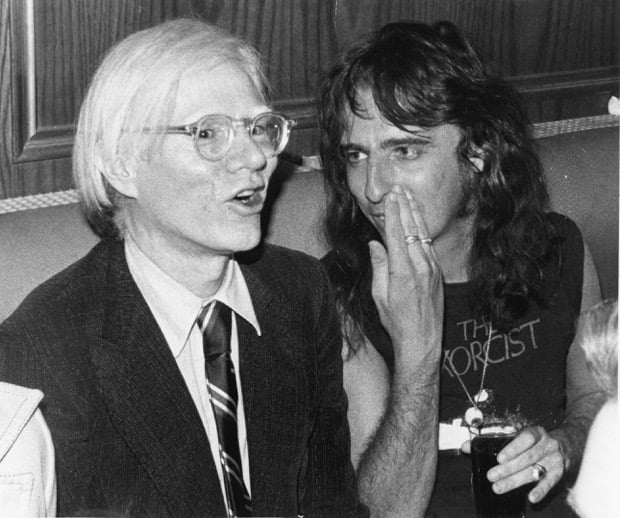

Although the silkscreen is unsigned, Polsky believes it is the real thing. He told artnet News: “Everything checked out. Alice and Andy were good friends in the early ’70s when Alice was in his prime.” Gordon confirms the two celebrities ran in the same circles: “Alice went to Studio 54 with Andy on many occasions,” he said.

Polsky has dated the 22-by-28-inch work to 1964-65 and plans to include it in his new, unauthorized addendum to the Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, which officially launches today.

“When they bought the painting, Andy had a number of electric chairs in his flat files, so it was a canvas but they had never been stretched,” Polsky explained. He has recommended a New York company to stretch the canvas (though he emphasizes that his involvement ends there, as his policy is not to be involved in buying or selling work that he has authenticated).

What’s next for Cooper and his painting? A sale is possible, says Gordon. (It’s unclear how major auction houses would regard an unsigned work authenticated by Polsky; many auction houses continue to run works by artist foundations before offering them for sale, whether or not that foundation operates an official authentication service.)

The artnet Price Database lists hundreds of Warhol electric chairs in all colors and sizes. The top price paid for a Little Electric Chair is $11.6 million at Christie’s in November 2015 for a green version dated 1964. That work is in the official Warhol catalogue raisonné issued by the foundation. Editioned prints of the subject would typically fetch about $10,000 each, experts say.

For now, however, Gordon says Cooper plans to hang the work in his home—at least for a while.