Language shapes our reality. It defines our perceptions of our allies, our enemies, and how much danger we think we’re in at any given moment. The Blue Lives Matter movement, begun by police officers in paranoid response to Black Lives Matter activism, crystallizes this dynamic in contemporary American life. Opening tonight, a new exhibition gives a fittingly surreal form to the rhetorically bizarre and potentially deadly force that Blue Lives Matter embodies.

“I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die)” is the first solo exhibition at Brooklyn’s Koenig & Clinton by American Artist, a young cross-disciplinary talent invested in issues of representation and concealed power. Artist legally changed their name in 2013 and opts for gender neutral pronouns, partly to expand conceptions of who deserves the loaded designation now doubling as their government moniker. However, Artist identifies as African American, adding personal resonance to the epidemic of police violence in the US so disproportionately affecting people of color.

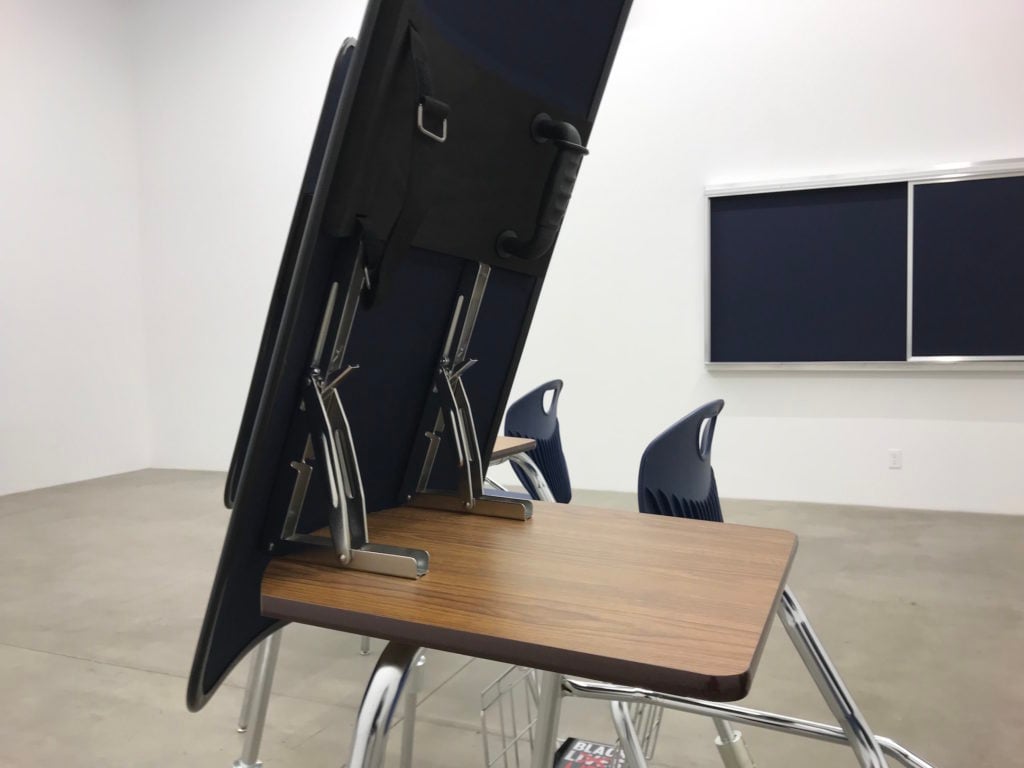

Artist’s new installation, which opens on March 1, implies that violence by fashioning a dystopian law-enforcement seminar. Lined up like a police barricade under flat fluorescent lighting are six sculptures that Artist refers to as “fortified desks.” Built to be loftier than average classroom furniture—Artist, who is over six feet tall, says their feet dangle when they sit in one—each work is a troubling mixture of typical desk and riot gear. Beefy metal brackets seemingly ready the legs for war, while a large shield covered in deep blue fabric extends from the wooden desktop as a defense mechanism.

American Artist, installation view of “I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die),” 2019. Photography by American Artist, Brooklyn. Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, Brooklyn.

These shields don’t just protect. They obscure. Anyone seated at a sculpture would be unable to see anything beyond the strap, handle, and mounting brackets on the reverse side of their shield. Similarly, a wall-mounted sculpture alludes to a university-style blackboard, but it too is shrouded in the same deep blue fabric. The message is clear: This seminar is primarily designed to reinforce in its attendees the blinkered notion that they are under attack.

But the centerpiece of the show pushes back against that perception. At one end of the gallery, a large, wheeled flat-screen monitor loops a computer-animated video that acts as a conceptual force-multiplier for the installation and the dangerous misconceptions driving its creation.

American Artist, installation view of “I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die),” 2019. Photography by American Artist, Brooklyn. Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, Brooklyn.

Protect the Shield

The exhibition’s genesis lies in a series of bills that penalize crimes against American law enforcement officers in similar ways as hate crimes. The first of these was ratified in Louisiana in 2016. Similar legislation followed in other states, and Congress could now apply the same problematic protections nationwide through the Protect and Serve Act, which sailed through the House of Representatives in May 2018.

“Blue Lives Matter frames ‘police officer’ as if it’s a social identity,” Artist tells artnet News. The proposition is simultaneously novel and absurd, since hate-crime legislation specifically exists to protect people of races, religions, genders, sexual orientations, and/or disabilities that have suffered systemic abuse for decades. Law enforcement is an occupation, not a personal characteristic—a framework that Artist sought to amplify ”to shift the conversation in a way that’s really fraught.”

In 2018, a coalition of prominent social-justice organizations headlined by the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch co-authored a letter imploring Senators to reject the Protect and Serve Act for numerous reasons, including that it “signals that there is a ‘war on police,’ which is not only untrue, but an unhelpful and dangerous narrative to uplift.”

This phantom war returns us to the video on Artist’s conference-room monitor. It consists of a nearly 20-minute monologue delivered by a mash-up of an unlikely duo: Dr. Manhattan, the omnipotent blue super-being from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s classic graphic novel Watchmen, and Christopher Dorner, a former Los Angeles Police Department officer who began a vengeful killing spree against his old colleagues in 2013 in the name of racial injustice.

The video’s protagonist blends Dr. Manhattan and Dorner on visual and verbal levels. The character’s look combines Dorner’s features and stature with Manhattan’s blue skin tone, glazed eyes, and atomic forehead-insignia. Its fiery monologue integrates original writing by Artist from the perspective of Dr. Manhattan and actual lines from the chilling manifesto Dorner wrote before leading Southern California law enforcement on a frantic nine-day manhunt that terrorized multiple innocent bystanders and ultimately left five dead, including Dorner himself. By design, it can be difficult to know which words originate from which source.

Cover of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Artist says they wanted to synthesize Manhattan and Dorner because of the parallel in their relationships to state power. In the Watchmen mythology, after a nuclear accident imbues Manhattan with god-like abilities that enable him to solve any problem, the US government attempts to militarize him. Disillusioned, Manhattan “retreats to Mars as a divestment from being a weapon of the state,” explains Artist.

In his manifesto, Dorner, who was African American, frames his actions as a revolt against the “blue line” that “prevents officers from reporting excessive use of force, often used against black people and people of color more than other people arrested,” says Artist. Unlike Manhattan’s pacifist self-exile, though, Dorner responded to this betrayal with murder.

Still, Artist finds a point of convergence between them. “The quotes from Dorner are from the manifesto, before he does anything [else],” they clarify. Like Dr. Manhattan alone on Mars, “they’re both so distraught that they need to say something, but what form that takes is not yet determined.” Artist’s uncanny installation, on the other hand, is a tangible reality now—and it colors the Blue Lives Matter movement in urgent new shades.

American Artist’s “I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die)” is on view through Saturday, April 13, 2019 at Koenig & Clinton, 1329 Willoughby Avenue, Brooklyn.