It’s easy enough for the average person to understand the frustrations of an artist who sees their work being associated with a cause counter to the intended message. Just think of Prince’s estate demanding that Donald Trump stop playing Purple Rain at campaign rallies in 2018. A far less familiar concept is what an artist goes through when their work resonates so strongly among like minds that it is taken up as a banner of the collective pain and injustice that motivated the work. How do you process your creations becoming synonymous with trauma, even when calling attention to the source of the trauma was part of the point of creating?

The artist officially known only as American Artist has been grappling with this dilemma lately. Ever since the latest wave of lethal police violence began crashing onto innocent Black Americans in May 2020, American Artist has seen an array of people on social media illustrating their denunciations of white supremacy inside and outside law enforcement with images of the installations, new-media works, and sculptures Artist has created to interrogate that same malignant force.

Artist, who identifies as Black, is no stranger to living with the tensions around institutional racism and technology. They legally changed their name in 2013 both to diversify the demographics called to mind by the phrase “American artist,” as well as to maximize their own anonymity in our ever-encroaching surveillance state. They agreed to an interview with Artnet News not to talk about their own personal struggles, but rather to try to alert the widest possible audience to the ways Silicon Valley, American law enforcement, and violent discrimination against Black citizens are conjoined in the institutions that define life (and too often, death) on US soil.

The interview took place over email during a week that included the disbanding of the NYPD’s notoriously aggressive plainclothes division and the murder of Rayshard Brooks by police in an Atlanta fast-food drive-through lane, among other signal events in the US’s continuing civil-rights struggle. The exchange has been condensed and edited for clarity.

American Artist, installation view of “My Blue Window” at the Queens Museum, New York. Photography by Hai Zhang. Courtesy of American Artist.

Let’s start with the big picture and zoom in from there. Your work is informed by a host of critical disciplines, but technology and police violence have been two of its dominant subjects. Often, those subjects intertwine, largely through the premise that white supremacy has been embedded in both Silicon Valley and American police forces from the start. I know the full answer could be a book, but can you tease out the relationship between the two realms a bit?

Well, first off, I want to say that this interview is happening in the wake of nationwide protests in response to the murders by police of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, among others. I state that to suggest why we’re talking today. You’ve been supportive of my work for some time and we would have done an interview at one time or another, but their murders are the reason it is happening right now.

Let’s talk about my practice as one that exposes the lineage of systems of control, in this case Silicon Valley and the police. However, I don’t want to position my criticality as a “subject” matter. Everyone’s work is political, though not all of it is critical. My art has been referenced over the last few weeks as a means of recognition, and while it’s reassuring to witness a connection of dots between things I’ve said and what is happening in the world, the events that took place in order for that recognition to occur are terrible.

The relationship between Silicon Valley and the police is an economic one at the expense of people’s lives. One example is the contracting of policing softwares for facial recognition, predictive analytics, and crime reduction from tech firms. Silicon Valley’s relationship to the military is that it was historically made possible by military funding (as well as any digital device you use). For the police, excess military equipment is given to local police departments to use, which became widely recognized during protests in Ferguson, Missouri [in 2014]. As you mentioned, there is a lot to say. These fields are historically linked.

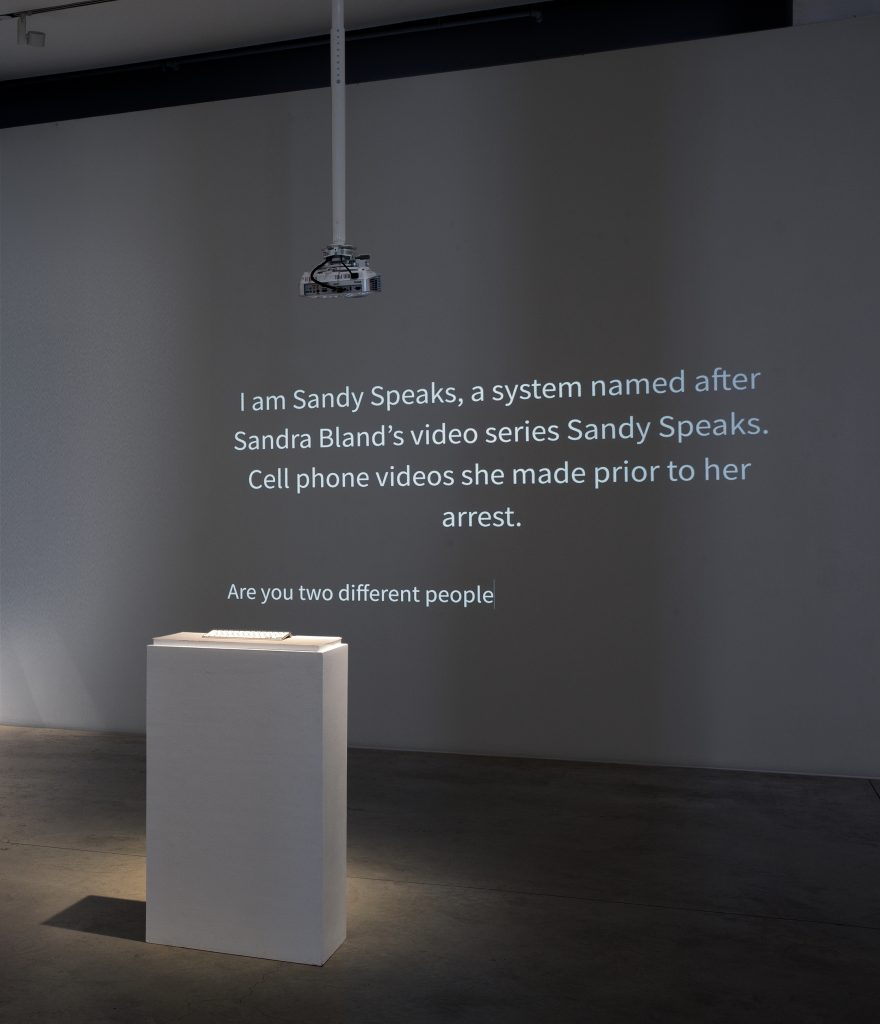

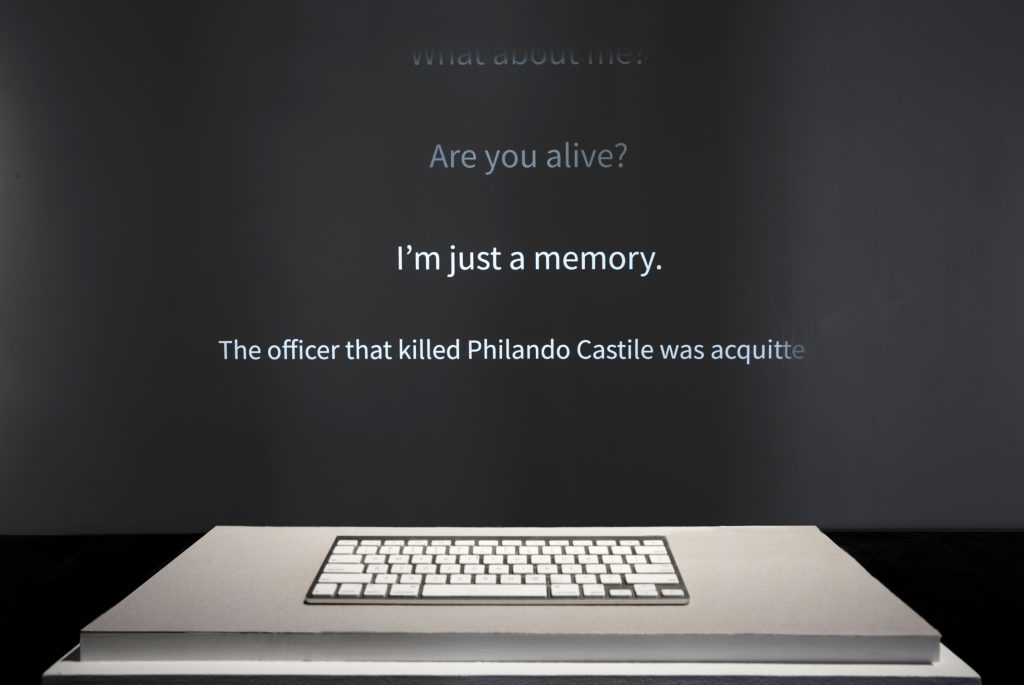

American Artist, Sandy Speaks (2016). Photography by Marc Brems Tatti. Courtesy of American Artist.

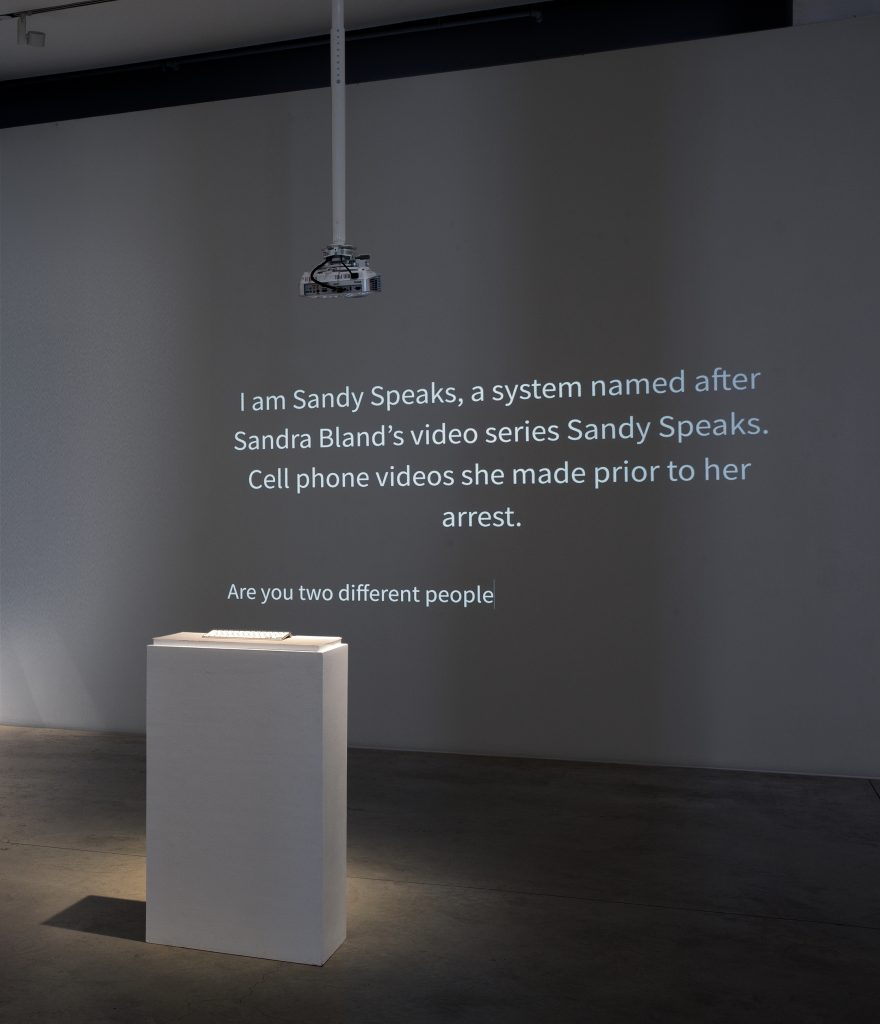

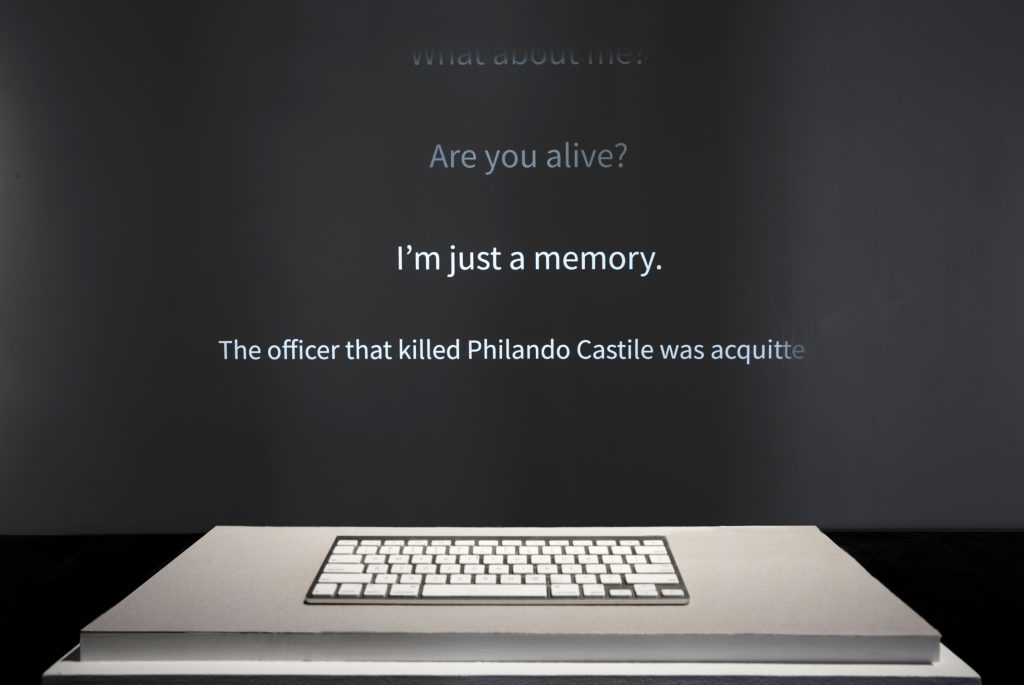

To my knowledge, the first work you made that was explicitly about systemic racism in American policing was Sandy Speaks (2016), a chat platform designed to answer questions about prison surveillance, police brutality, and its namesake, Sandra Bland, who died in a Texas jail cell three days after being pulled over for changing lanes without signaling. What was it about that tragedy or that moment in time that compelled you to address the subject directly in your studio practice?

Sandra Bland had been making an online video series called Sandy Speaks that she published on Facebook. She would begin each video by saying “good morning Kings and Queens,” and the videos were her personal reflections of her own experiences and her interest in wanting to teach children—Black children—that maybe they could have better race relations in their generation. If they understood where police were coming from, and the police understood them, they could find common ground. She felt it was her calling to teach children. She spoke about this in some of her videos.

Part of the intent of my work is to limit the racial divide around networked technology. Bland’s video series was social media use by and for Black people. Hearing her say those things on social media was impactful. The conversation around [Bland’s] virality is that of the video of her encounter with the police, but I wanted to focus on what she was saying before that in these videos.

Chatbots are most often used as a means to outsource labor that would otherwise have to be done by a human. They also have a reputation for leaving users dissatisfied with the limited answers they’re capable of giving. How, if at all, are those two traits at work in Sandy Speaks, especially with regard to the audience demographics in the average museum or gallery show?

Chatbots, like other forms of bureaucracy, are known for obfuscating vital information. It’s similar to the relationship you have seeking help from a government agency. I wanted Sandy Speaks to have the opposite effect—to provide information that is normally hidden, and to encourage people to seek answers they wouldn’t normally have access to. Because of the limited scope of the bot, even though it was prepared to answer a couple hundred questions, it wasn’t enough to account for all the ways people approached it. People took this as a commentary on the process of using a bot, and felt it was appropriate that the bot be selective in providing answers.

Jenny Holzer recently created a piece projected in Manhattan that displayed the last words of George Floyd. It visually reminded me of the interface of Sandy Speaks. I think it’s important commentary on what information we are able and ready to hear, as far as obfuscation. We’ve seen the footage of Floyd—it’s hard to escape—but what about his words? With Sandy Speaks, I wanted to create an object that would memorialize her in a way that could change and evolve and didn’t feel sedimentary. I see something parallel in this work.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBcEH_3Aj-4/

In 2019, you had a solo exhibition at the (now disbanded) Brooklyn gallery Koenig and Clinton titled “I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die).” Its genesis was the Protect and Serve Act, a 2018 bill that sought to classify violence against American police as a hate crime. What was it about the proposed law that motivated you to create the sculptures and video installation in the show, and how is the argument behind it reflected in the current Black Lives Matter protests?

The installation I made for Koenig and Clinton resembled a classroom. I wanted to paint a portrait of “blue life,” and address the absurdity of it. The Protect and Serve Act, also known as the Blue Lives Matter Bill, came out of the #BlueLivesMatter movement, which was a response to #BlackLivesMatter. Blue Lives Matter considers police officers as a social group under threat.

The sculptures in the exhibition reference the fragility of the police—something we are seeing the effects of at this moment. The Minneapolis police were charged with the murder of George Floyd relatively swiftly. In the past, it’s been nearly impossible for the police to accept any responsibility for their actions. I wanted to make a point that the defensiveness of the police comes from a place of dangerous insecurity, preventing them from hearing plights of breathlessness made by the people.

Before I created the show I read an essay called “Blue Life” that describes blueness as an embodiment of state power. I found it very eerie to think of blueness in this way, and it led to some of the choices in the exhibition. The video features a blue character that reprimands the (police) audience for choosing to identify as blue.

American Artist, installation view of “I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die)” at Koenig & Clinton, New York, in 2019. Photography by Jeffrey Sturges. Courtesy of American Artist.

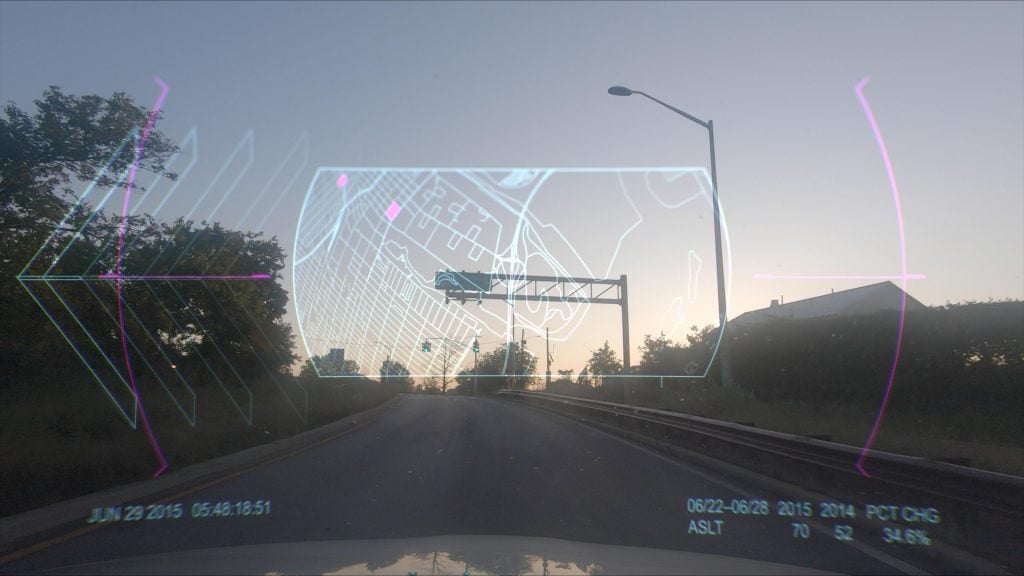

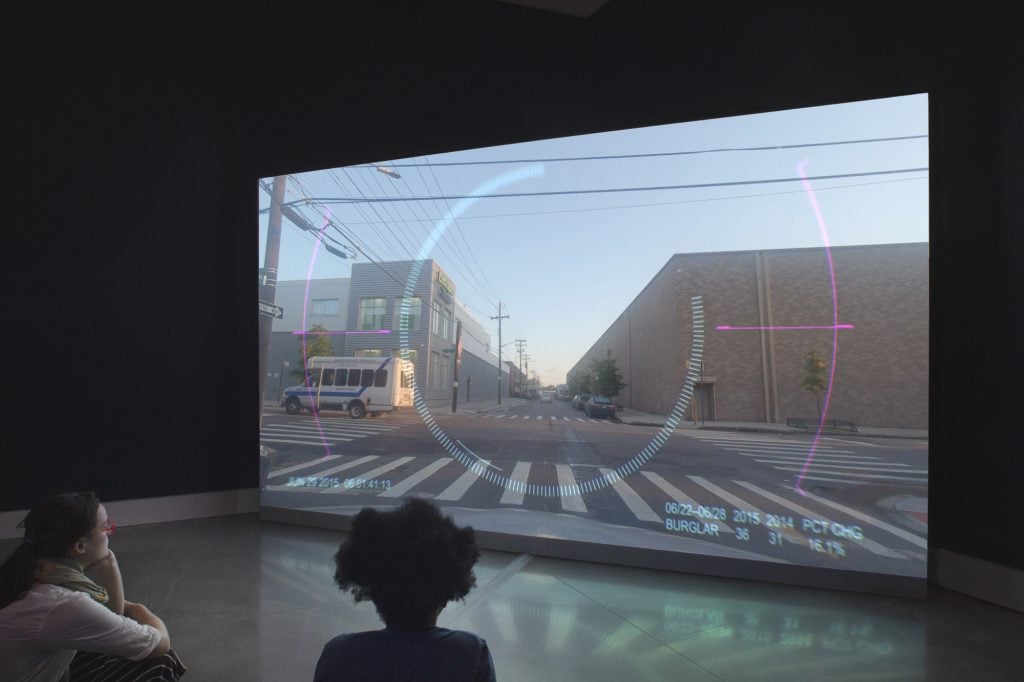

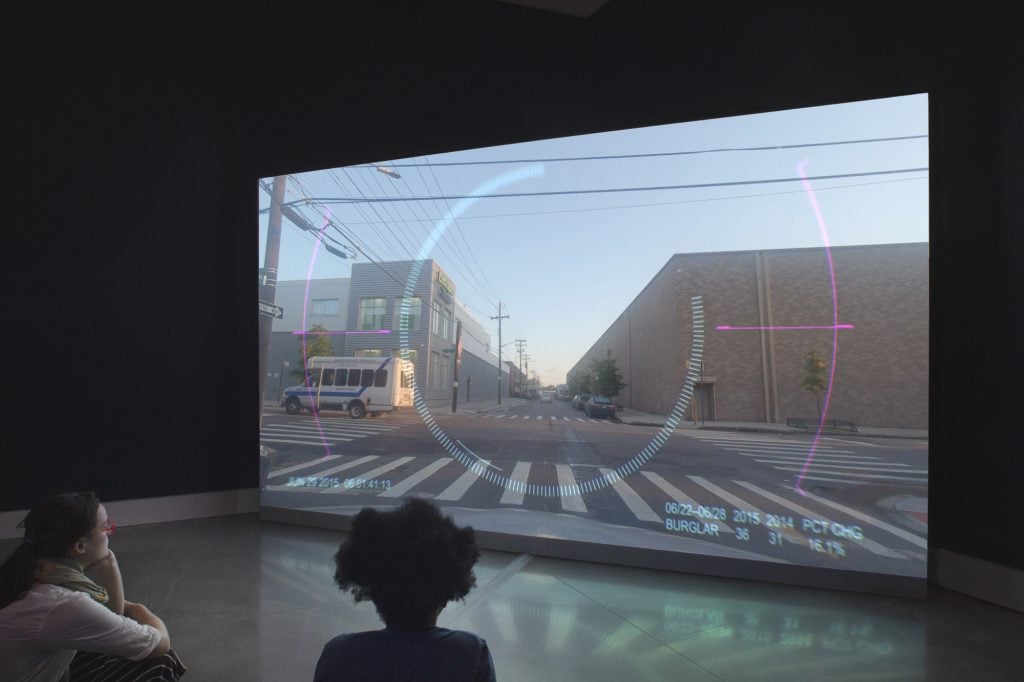

The centerpiece of your recent solo show at the Queens Museum was 2015, a video installation that addressed predictive policing, in which officers’ strategies are informed by forecasts about where, when, and what types of crime will occur based on historical data. The video itself might look like a sci-fi trope to the uninitiated, with street maps, crime statistics, and notifications streaming over the driver’s-eye view from a police cruiser on patrol. Can you tell me a bit about the origins and aims of that work?

When you watch the film, you are driving around Brooklyn, beginning in East New York, then Brownsville, and then East Flatbush. It’s separated into six short vignettes where you see the software performing in different ways. In the second clip, the driver rides down a street with several people on it who hastily avoid the gaze of the vehicle. As the people move out of the way of the car, a light-colored box attempts to frame and identify them. The siren of the police car is blaring the whole time, and by the end of the block the interface on the windshield of the car updates to show the words “crime deterred.” The impression of a non-event is both violent and mundane, and describes the nature of police surveillance.

The video takes place in the past. The NYPD began using predictive policing in 2015—possibly even earlier. Even though the film resembles a futuristic view of policing, I set it in the past to show how normal the software actually is. Even though the real software isn’t as cinematic and “sci-fi” looking as it looks in my film, it is complex and uses past data produced by police. It’s biased data that increases the presence of cops and the frequency of arrests in Black and brown neighborhoods.

American Artist, installation view of “My Blue Window” at the Queens Museum, New York. Photography by Hai Zhang. Courtesy of American Artist.

In a recent interview, you referenced scholar Simone Browne’s portrayal of the brands seared into enslaved people’s skin as an early form of biometric technology, i.e. hardware and software that translates our identities and traits into data for other systems to process. Biometric tech such as facial-recognition algorithms are already being used by law enforcement both here in the US and abroad, particularly in China. Contrary to claims made by its advocates, is this more advanced technology actually just proof that policing is immune to real change?

Americans look at Chinese surveillance to justify our environment as less bad, but as it is painfully clear in the first line of your question, the relationship between surveillance and anti-Blackness in the United States is as American as apple pie. The problem with generalizing “surveillance” as non-differential is that it isn’t true. Not everyone entered this country as a commodity. Tools that evolved from the ones used to keep track of those (human) commodities carry the same biases. The critique of technology in my work gives an entry point for white viewers to entertain the idea that racism and bias wasn’t resolved in the 1960s.

I like the last part of your question because it gives some room to plug abolishing the police. Organizer Mariame Kaba recently published an op-ed in the New York Times giving some background to the argument for this.

American Artist, Sandy Speaks (2016). Photography by Marc Brems Tatti. Courtesy of American Artist.

The cultural critic Wesley Morris recently led a piece in the New York Times with the following statement about the footage of George Floyd’s murder (and police brutality more broadly): “The most urgent filmmaking anybody’s doing in this country right now is by Black people with camera phones…. Art is not the intent. These videos are the stone truth.” I’m curious to know your reaction to that idea, particularly since it foregrounds that Black Americans are using one product of white supremacy against another to try to rupture a corrupt system. Is it a reason for hope, a reinforcement of tragedy, or something else?

Black Americans have always primarily had the tools of white supremacy at their disposal. Whether those tools are effective in dismantling white supremacy is debatable.

What I think is uniquely Black is the way we refashion those tools. Though footages of Black pain circulate in a continuum of lynching graphics that were popular in the states for decades, there are artists that have taken up the “stone truth” and used it as a means of activation. I’m thinking of Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death—which remixed a lot of this footage—or Ja’Tovia Gary’s Giverny I (Négresse Impériale)—which included footage from the video of [the police killing of] Philando Castile. Or Cameron Rowland’s recitation of lynching statistics written by Ida B. Wells. Though it wasn’t visual, it reproduced and transformed this data into something else.

What I find significant about these footages isn’t the device used to capture them but their ability to circulate virally, which wasn’t possible 20 years ago. Similar to the early usage of #BlackLivesMatter, it organizes Black people across the United States in a collective desire for indemnity.