Analysis

How to Make Sense of Today’s Soaring Auction Prices Using Art Market Data

Take a look back at some of the art market's historical highs and lows.

Take a look back at some of the art market's historical highs and lows.

Eileen Kinsella

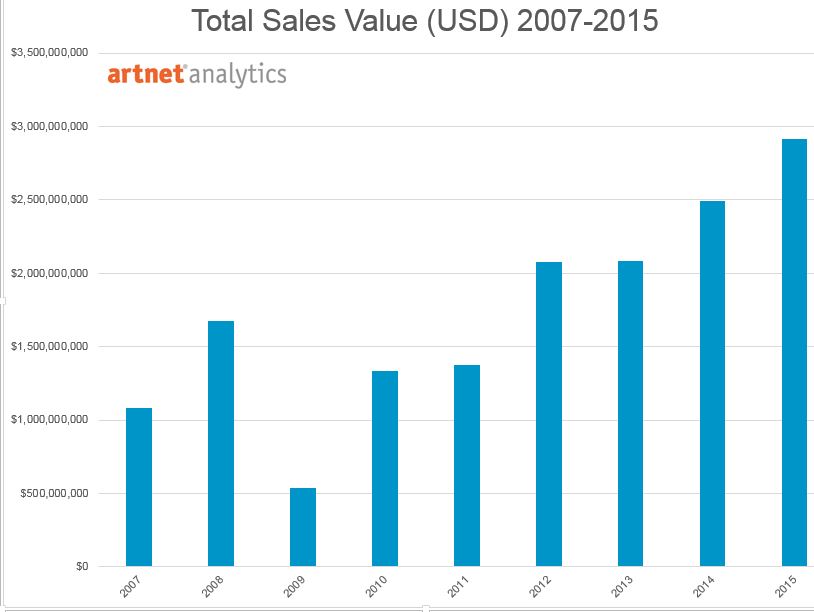

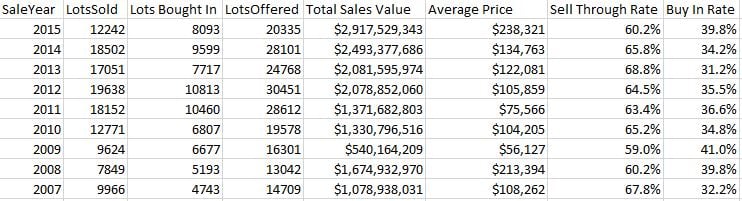

Fine art auctions for the first half of May, from 2007 to 2015.

Source: artnet Analytics.

The recent record-shattering spring auction season in which a Picasso painting became the most expensive work ever to sell at auction, for $179.4 million, at Christie’s New York, was unprecedented on a number of levels. It was in many ways a game-changing auction (see 10 Game Changing Auctions).

The new record set by the Picasso is a whopping $37-million increase on the previous high of $142.4 million, paid for Francis Bacon’s triptych Three Studies of Lucian Freud in November 2013, also at Christie’s. It also marks the first time that the price of a painting—adjusted for inflation—surpassed the $82.5-million record set when a Japanese paper tycoon purchased Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet (again at Christie’s) in 1990.

Almost immediately after that headline-grabbing Van Gogh sale, however, the market spiraled into a prolonged downturn. To give you an idea of the totals back then, one major May 1992 postwar and contemporary art sale at Sotheby’s totaled $23 million, falling short of its $35 million estimate. What a different world we live in today where single paintings regularly surpass, double, or triple previous auction night totals.

It wasn’t until 14 years after Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet sold, in 2004, that a single painting—Picasso’s Boy With A Pipe—simultaneously surpassed that price and broke the $100-million mark at Sotheby’s. That is a long auction drought.

Alberto Giacometti, Pointing Man (1947), bronze with patina, hand-painted sold for $141.3 million at Christie’s, becoming the most expensive sculpture ever sold at auction.

Photo: Courtesy Christie’s.

In the early 2000s, as the art market started to regather steam, a typical two-week spring or fall New York auction season—including both the Impressionist and modern as well as postwar and contemporary art categories—would often tally anywhere from $300 million to $500 million. That’s a big increase on the totals for the early 1990s but, again, small in comparison to today: Now Christie’s and Sotheby’s alone pull in that much—and, increasingly often, far more—in a single evening.

Here are 2015 totals for those that have already forgotten: Sotheby’s Impressionist and modern art sale earlier this month, scored just under $380 million, and its contemporary art evening sale on May 12, hit $368 million (see Sotheby’s Stellar $380 Million Evening Sale Not Without a Few Bumps and Mysterious Asian Buyer Causes Sensation at Sotheby’s $368 Million Sale). Christie’s realized a total of $705 million with its May 11 “Looking Forward to the Past” sale, spanning Impressionism to contemporary art, and another $658 million in a standalone postwar and contemporary art sale two nights later (see $179 Million Picasso Sets Stratospheric Record at Christie’s Looking Forward to the Past Sale and Record Shattering Picasso Sale Heralds Beginning of End of Market Boom).

Back in 2007, during the market’s last great peak, Christie’s $71.1-million sale of Andy Warhol’s Green Car Crash I (1963) and Sotheby’s $72.8-million sale of a Mark Rothko classic color block painting, once owned by David Rockefeller, left many market observers speechless. At the time, there was fevered talk of the possibility of a $1-billion season. It didn’t happen, even then. Fast forward to today and in the second week of May this year, Christie’s New York single-handedly accomplished a $1.36-billion tally with just two sales.

Of course, following that 2007 high, things did cool considerably—as evidenced by the steep drop in totals in the May 2009 season to roughly $540 million—but the slowdown was short-lived. Warhol prices have twice leapfrogged the number paid for Green Car Crash, with $105 million paid for the diptych Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) (1963), at Sotheby’s New York in November 2013, and $81.9 million paid for Triple Elvis (1963) at Christie’s this past November.

Works by Rothko have also since surpassed the 2007 auction record high, three times actually, including the new record of $86.8 paid for Orange Red Yellow (1961) at Christie’s New York in November 2012.

What is more surprising, given the sharp ups and downs in auction totals, is the relative steadiness of the percentage of works that sell at auction, which the auction houses call the “sell through” rate. Meantime works that go unsold are referred to as having been “bought in.” According to artnet Analytics data (see table above), that figure has remained between about 60 and 70 percent over the past eight years, countering the conventional art market wisdom that the number of unsold lots tends to rise when the art market slows: according to a 1992 New York Times report about the art market doldrums, for example, not only were prices plummeting but “large numbers of works . . . failed to sell because no one was willing to meet the reserve—the minimum price the seller is willing to accept at auction.” Today, the analytics show, this is no longer the case.

According to the data, the recent $2 billion-plus season—the highest yet—had one of the lowest sell-through rates, at 60.2 percent, equal to the spring 2008 season when the auction market started to slow. The sell rate was highest in 2013, when nearly 69 percent of lots found buyers.